“Preaching to the choir” is as good a way as any to describe it.

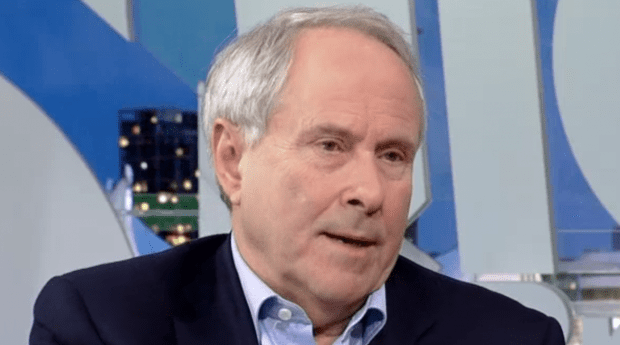

Tom Flanagan is standing at a lectern, delivering the story of his own political demise in his typically meandering, tangential style. He ranges from self-deprecation to academic storyteller to self-pity, bordering on a persecution complex. But the former University of Calgary political science professor turned brain trust for the Reform Party and, eventually, senior advisor to Stephen Harper, is — love him or hate him — unfailingly compelling.

“I was virtually mobbed,” Flanagan says to the three-dozen-odd attendees smattered throughout the auditorium. “I mean, I wasn’t told, ‘Up against the wall, motherfucker!’”

A few people in the room titter at this comment.

The event is put on by the Free Thinking Film Society — a small-C conservative group with a libertarian bent — which is just about the most receptive group of people for Flanagan’s message that you’re going to find. And Flanagan needed some friendly faces.

It had been just about a year since Flanagan made the comments that led to his public flogging.

It was a YouTube video that all but destroyed his professional career. In it, the academic is shifting weight from one foot to the other as an Idle No More activist in the crowd asks a series of loosely connected questions — how does eliminating the reserve system help First Nations, how do your theories on the Indian Act actually solve problems facing aboriginal peoples in Canada, and, finally, why are you okay with child pornography?

The sneak attack was sparked by comments that Flanagan once made to a University of Manitoba newspaper. He mused, briefly, about whether locking people up for looking at what are, essentially, “just pictures,” is really good public policy.

“A lot of people on my side of the spectrum, on the conservative side of the spectrum, are on a kind of jihad against pornography and child pornography in particular. And I certainly have no sympathy for child molesters. But I do have some grave doubts about putting people in jail for their taste in pictures.”

There are a few gasps. “That’s disgusting,” one person yells. The crowd wasn’t exactly friendly, anyway. Flanagan has become a pariah for many Canadian indigenous people, as he has a habit of making cavalier comments about their history, as well as penning several controversial books advocating for the integration of Canadian First Nations.

Just the same, Flanagan tries to muddle through the answer but eventually is shouted down. He moves on to another answer as the YouTube clip ends.

What came after is the basis for Flanagan’s book, Persona Non Grata, and the excuse for holding the event with the rightwing film society at the Library and Archives Canada auditorium in Ottawa.

He left the University of Lethbridge, where the infamous video was shot, the morning after the talk — which was actually on aboriginal affairs, hence the hostile crowd — just as the video was making the rounds. By the time he got in his car and drove off, embarking on the two-and-a-half hour jaunt from southern Alberta to Calgary, controversy was swirling.

Flanagan likens it to Franz Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. He went from man to cockroach in just a two-and-a-half-hour drive. “I left Lethbridge as a respected academic and public commentator and arrived in Calgary as persona non grata,” he writes in the book.

Flanagan was cast out, admonished and ultimately exiled by virtually every one of his friends — from Alberta Wildrose Party leader Danielle Smith to the prime minister, his university and everyone in-between.

His story is a cautionary tale but not a new one.

Academia alone has a long and storied history of targeting its own to be run out of town on a rail, academic freedom be damned. Gay and transgender teachers still regularly get the boot in the Western world, though the pendulum has recently swung toward ousting professors with anti-gay sentiments.

The instances of anti-gay witch hunts in academia are too numerous to name. One prominent example, however, came after the University of Lincoln-Nebraska introduced one of the world’s first dedicated queer studies classes, in 1970. That led to the state legislature considering a bill, ultimately defeated, that would have banned the teaching of anything to do with homosexuality outright.

Here in Canada, the RCMP and the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) were tasked with rooting out homosexuals from the public service and any other facet where they could be found. Openly gay Canadians could be fired purely because of their sexual orientation until the mid 1990s.

Fear of pedophilia was often listed as an excuse for rooting out the gay scourge in education.

Flanagan crafts this idea into a global theory of “moral panic” and “folk devils.” The panic — whether it be child pornography, satanic cults, communism or homosexuality — is the excuse for targeting those folk devils — those who are stymied by association with the issue.

“Moral panic and the excitement of mobbing triumphed over all normal canons of journalism, because folk devils have no right to speak,” he writes of his own situation.

Flanagan, of course, notes that pedophilia and child pornography are inherently wrong and cause enormous ills on those affected. And that moral panic, often fuelled by a national security or public safety narrative, often overrides citizens’ better judgment, cajoling them into supporting measures that would otherwise be unpalatable — everything from the Patriot Act to the Salem witch trials.

So when Flanagan questioned imposing a one-size-fits-all punishment for a crime that has no direct victim — but which does cause incidental or secondary harm — the nuance of his position was lost in the fray of moral panic.

Yet his point is an astute one. At the Free Thinking Film Society event, he set up a dichotomy of a man coming back from Japan with manga cartoons depicting nominally underage girls and a man who trades videos of pre-pubescent children. Are they equally blameworthy?

Once you accept that there may be some inherent disproportionality, other questions arise: is it equally as blameworthy to watch an explicit video of a 16-year-old girl as watching a similar video of an eight-year-old boy? And what of the research that shows a weak link between viewers of child pornography and those who actually go on to molest children?

While the small contingent of free thinkers in the audience was at least open to the conversation, they still looked visibly uncomfortable with the direction of the talk. If Flanagan had made the statement nationally, the hellfire would have been scorching.

But, with the controversy that he did bring upon himself, the reaction was interesting. Some, like Policy Options (an academic magazine) and the CBC, immediately cut ties with Flanagan, refusing his views outright. Others, like the National Post, Maclean’s and TVO (Ontario’s public broadcaster) were happy to give Flanagan a platform on which to defend himself. But the damage was done, and the debate was no longer about the topic at hand: discussions of child pornography outside the accepted parameters of absolution were not to be had.

Flanagan’s mobbing is emblematic of a shift. While, once, those who attracted controversy were hauled in front of a committee, like the communists; outed, like the gays; or generally dismissed, like the feminists, those of unpopular opinion today face a reputation-obliterating pile-on.

I wrote about that notion for a recent Xtra cover story — Raging Homos — where I posited that the gay lobby has become the bully. But, of course, it’s not just the gays. Social media and a rapid-fire news cycle has given us an unnervingly efficient guillotine for those whose views we find, rightfully or wrongfully, to be unpleasant.

Flanagan’s story is an interesting case study of group-think and the subjugation of thought. Perhaps, next time, we should all take a breath before we hoist the noose.

I asked Flanagan a few further questions:

If you had to give a prognosis on the state of free speech in Canada, what would it be?

It’s one of these never-ending battles. I don’t say that free speech is doomed; I just think that the battle is never won. Different issues are constantly arising, and people need to be prepared to take on these issues. I mean, I’m basically optimistic, but I don’t think it’s necessarily easy. I think people need to keep fighting.

In there, you were pretty critical of the Conservatives’ tough-on-crime agenda. On some of these big-button issues, like prostitution, where do think the government falls?

Well, I fear with prostitution that they’re going to adopt the Nordic model, so it’s another form of repression. I like to think that I’m more of a realist. I don’t think you can ever put an end to the market for sex, just as you can’t stop people from craving various kind of drugs, even though they’re illegal. So, I think the Conservatives will opt for probably a repressive version of the Nordic model and start charging different people, but they still want to charge somebody. I’d prefer not to be charging anybody.

Do you think there’s any possibility that we’ll take a more nuanced approach to child pornography in the future, or will we continue down this path of further criminalization?

Obviously, it’s going to take a change of government before we change directions, because the government is still announcing more oppressive measures on all kinds of fronts, including child pornography — they want to raise the mandatory minimum from six months to a year — so it’s pretty clear that, in the short run, at least, we’re going to continue down the same path. Now, in a longer term, with different people in power, either a different conservative leader or different leader, things may be different.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra