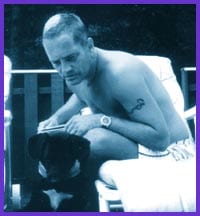

“Back then I was a happy house husband,” says Terry Goodwin, of life before AIDS and before his own lover died. “I had a good income, and I lived to party.”

Goodwin, 44, landed in quarantine in Vancouver in October 1984, and came out with an HIV diagnosis. Fighting infections and two bouts of cancer, he spent the next decade working his ass off for AIDS organizations.

“I guess gay politics was more of a lark to me,” he says of his younger days. “AIDS activism was more personal.”

But by anyone’s standards, Goodwin’s been around. At New Brunswick’s Mount Allison University in the early 1970s, an attempt to start a gay students’ organization ended with him being forced out of residence, after his door was kicked in and his room trashed – repeatedly.

Moving to Vancouver at age 20, he participated in the Gay Alliance’s “zaps” against the CBC for not covering the magazine Gay Tide’s lawsuit against the Vancouver Sun, which refused to carry ads for the mag.

“It was the first nice day of spring in April,” he says of one of the zaps, the most “fun” protest he’s ever been on. “We blocked off the street and had a picnic.”

It wasn’t until his AIDS diagnosis, though, that Goodwin became dedicated to making the world a better place.

“I’d never really thought of others before,” he says. “I realized I’d been blessed with a bit of intelligence and the ability to help.”

Goodwin became member number 39 of the Vancouver People With AIDS Coalition (it’s now the British Columbia People With AIDS Coalition, and has some 3,000 members). He was director of the PWA Housing Society, spent time working on income security and survivor benefits, and testified at the Senate hearings on euthanasia.

“Then my husband died.”

Don, Goodwin’s partner of 12 years, passed away from AIDS related illnesses in 1995.

Goodwin moved back to his home province of Nova Scotia.

“I was kind of burnt out.

“I’d been working in so many AIDS organizations. I’d lost over 350 friends and acquaintances.”

Goodwin spent five months alone in his parents’ cottage – then decided to stay.

“It’s my home,” he says of the province he was born in. “I have roots here.”

He lives in Lunenburg, a town of 2,500 that “has something for everyone.”

Since moving back, Goodwin’s been working with young people. He’s director of the Lunenburg Family Resource Centre, and spends his summers running an organic farm with teenagers at risk.

“I would have made a good dad,” he says. “A lesbian friend and I tried in the ’70s, but that’s before they had all these fancy ways to do it.”

Two months ago, Goodwin decided to go off AIDS medications completely. He’s been clear of cancer and related illnesses for five years, and believes that many of the drugs lead to complications such as diabetes. “If everything’s okay, I don’t see why I should be on anything,” he says.

His boyfriend, Will, lives a couple of towns up the coast. Goodwin shares his beautiful white clapboard house with a dog, Ariel. Their 19 acres of land are shared with a handful of humans, deer, partridges and pheasants.

“At this time of year you can look out of the window and see right to the harbour,” Goodwin says.

Goodwin’s webpage has resources for youth and people with HIV; it’s at http://members.tripod.com/tgoodwin.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra