This week marks the 23rd anniversary of World AIDS day. One of the things that AIDS has made us do is talk about it, to learn and understand it and the lives it affects. I’d like to share a few stories, if I may, about the people with HIV/AIDS who have affected me.

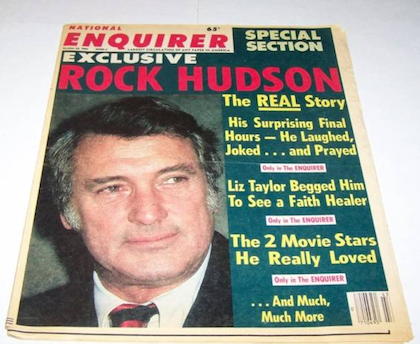

In 1985, my elderly neighbour showed me her copy of the National Enquirer. “He has that disease of the gays,” she said, pointing to a picture of Rock Hudson. I didn’t know who Rock Hudson was, but I had an idea of what gay meant, and what it meant to me. My nine-year-old brain thought that one day, because I was what that man was, I would also have what he had.

AIDS was a scary word to a nine-year-old. Our teachers weren’t talking about it, but it was on television. An episode of LA Law had Douglas Brackman convinced that he had contracted the virus. In a panic, he telephones a radio call-in show doctor. The doctor starts to name off various symptoms while a hypochondriac Brackman begins to “exhibit” some, wondering when he will show the others. The next day on the playground, my friends had to convince me that I didn’t have AIDS, because only gay people got it.

Little did they know.

Fast forward six years to junior high, when my eighth grade junior high teacher asks us to read a novel called Aller Retour by Québécois author Yves Beauchesne. I decide that I must meet this man, as he teaches at my local university. I knock on his door, and he greets me. He is handsome and very soft-spoken. I thank him for his time after I tell him how much I enjoyed his book. Three weeks later, Beauchesne is invited to come and speak to our class. The kid in front of me turns to me and says, “You should like this guy.” When I ask why, he says, “Because he’s a fruit like you.”

Beauchesne comes to the class and I do everything I can to avoid his gaze. He speaks to the class about writing the book, occasionally looking at me. I will do nothing to engage him or my classmates to make them think I know this thin man. Later at lunch, he comes and sits next to me, telling me that he is pleased to see me and that he is surprised that I was in the class he spoke to. I excuse myself, telling him I’ll be back.

I don’t come back.

A year or so later, Beauchesne dies from complications due to AIDS. I feel ashamed. Years later, when I attend the university where he taught, I tell this story to one of his old friends, who is head of the department where he taught. She soothes me and says that Yves would’ve understood. I sincerely hope so.

Three years later, I am the first and only kid to come out in my high school. I’m sitting with my entire high school in an auditorium while three people from Halifax are leading a presentation about HIV. One of them, a man in his 30s named Terry, discloses the fact that he is gay and HIV-positive. People start to look at me. Terry notices. He is strong, articulate and seemingly unafraid of a bunch of hormone-ridden kids who would do or say anything. At one point in the class, a kid asks him, “Do you like getting fucked in the ass?” A teacher starts to say something, but Terry calms the teacher down. He asks the kid to stand and says, “My sex life is my own. As is yours. Would you like it if I asked you the same question?” The kid mumbles and sits down.

I remember my experience with Yves and go up and introduce myself to Terry. I tell him I’m gay and he shakes my hand and praises me for being open. I tell him how I had been reading about HIV and AIDS, about groups like ACT UP, and about the AIDS Coalition in Halifax and how I want to get involved. I never see Terry again. I read his obituary years later.

Three people. One of whom I never met, one I shunned and another I admired. I grew up during the AIDS crisis while discovering my sexuality, something I can’t ignore. At this time of year, I believe it is important for me to remember these stories. That I remember these people.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra