Feb 5, 2016, is an important date for Toronto — 35 years ago, Toronto police raided the city’s gay bathhouses. More than 300 men were arrested, simply for being gay and open with their sexuality.

We remember this day not only for its infamy, but because this day in 1981 marks the time when gay men stood up and said they had had enough.

Over the next week, we will be looking back at that fateful day: at the activists who fought for their sexual freedom and continue the fight until this day; the homophobia and fear those men faced; and what we, as a country, need to learn from the bathhouse raids.

This article was originally published on Feb 7, 2014

It’s easy to forget what a different world Toronto was before that freezing February night in 1981 when the cops smashed their way through Toronto’s gay baths. It wasn’t much more than a decade after Stonewall. Church St’s gay village was in its infancy. There was no internet. Big house parties were still a regular way of meeting people. There were no annual Pride celebrations. No Xtra. No fab. No human rights protection. We could be fired from our jobs, thrown out of our apartments, denied services for simply being queer. After closing time, the streets could be dangerous places, due to both gaybashers and the police. Being out was still a major risk that most people approached very carefully.

On the other hand, there was a growing bar and bath culture and a vibrant, if small, gay liberation movement. The Body Politic came out most months of the year; Glad Day Bookshop was a centre for lesbian and gay literature unavailable anywhere else; groups such as the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario, the Lesbian Organization of Toronto, Gay Asians Toronto and Gays and Lesbians Against the Right Everywhere were active.

But there was often a huge cultural gulf between gay activist groups and the so-called regular people gravitating to the bar and bath scenes. These regular people often perceived activists as annoyances: politically correct troublemakers, always rocking the boat. For our part, we complained about some of those in the bar and bath scene as backward and closeted. We distrusted the owners of such establishments.

The bath raids changed all that. The regular people learned overnight the importance of political organization and leadership. Activists learned that regular people weren’t so backward after all, that once aroused they could be a potent political force. Everybody recognized that keeping gay-focused businesses open was essential to the health of the community.

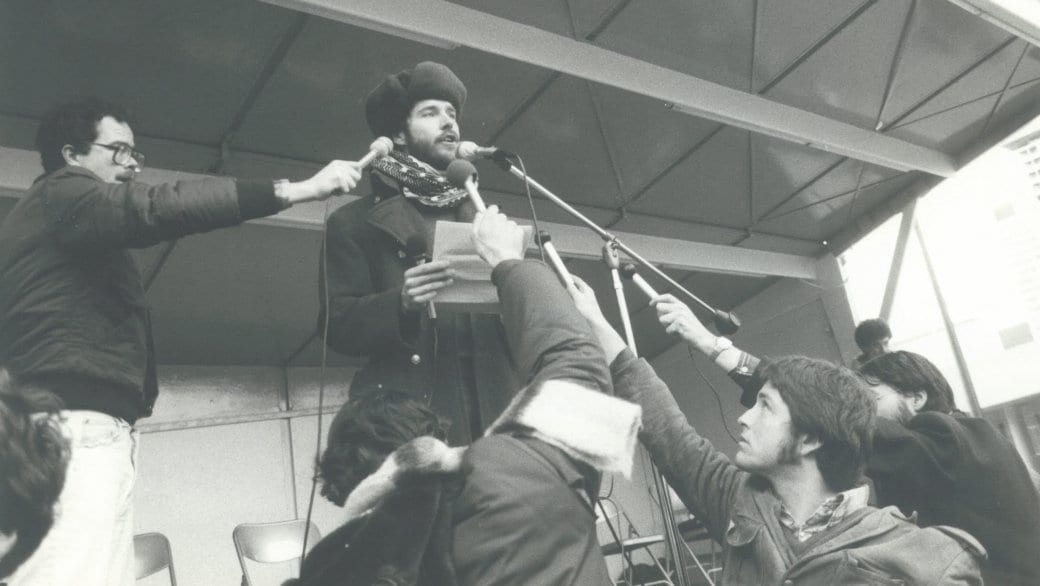

The Right to Privacy Committee (RTPC) led the response to the raids. Its steering committee included seasoned activists Michael Lynch, Gary Kinsman and George Smith, but there were also lots of people who weren’t previously publicly involved who brought new skills and energy essential to the success of the organization. Even the group’s name reflected this coming together of the previous solitudes: “rights” at the beginning and “privacy” at the end.

This consolidation of the notion of community was perhaps the most important legacy of the bath raids. We were no longer just individuals who went out on the weekends searching for sex or just business people serving a niche market. We were no longer just networks of friends and sexbuddies, drag queens and leathermen, clones or little activist groups that spent much of their time bitching about each other. We might have had lots of differences, but the police attack on the baths made us realize that we had to work together. That was the principle that governed the establishment of the first Toronto Lesbian and Gay Pride Day held six months after the raids, another consequence of that cold February night.

We learned from the bath-raids experience how to withstand a much more powerful opponent: the police and a court system intent on grinding up our institutions and sending us to jail. We learned how to form alliances with other groups facing similar issues. The widow of Jamaican Canadian Albert Johnson, for example, recounted at a post-raid rally how police shot and killed her unarmed husband in their home. We learned how to build and sustain our own institutions. As well as the demonstrations, the RTPC coordinated dozens of lawyers to fight those charged, raised thousands of dollars to ensure those arrested would have access to legal council, developed a media strategy, set up a Court Watch program to identify cases targeting gay men, and established a Gay Street Patrol to keep people safe from the wave of queerbashing that followed the raids.

Nowhere is this legacy more evident than in the fight against the AIDS epidemic that began to engulf our community just as the last bathhouse cases were finally clearing the courts. Once again we faced a powerful opponent. This time an epidemic was killing us, while an apathetic and indifferent government stood by. Lynch went on to become a founder of Toronto’s first AIDS organization, the AIDS Committee of Toronto. Kinsman was one of its first employees. The organizational and fundraising skills honed in the RTPC were put to good use in sustaining the new organization. And when AIDS began to spill out of the gay community and affect others, we remembered the importance of identifying a common cause and helped other communities to organize. Finally, unlike many other jurisdictions, our RTPC experience meant we kept our bathhouses open, turning them into places of outreach and schools of safer sex.

Some of the connections are even more striking. In 1981, following the raids, the RTPC reinvented itself as a powerful organization through a large public meeting held at Jarvis Collegiate. People recounted their personal stories of police brutality in the raids, expressed their anger and joined subcommittees to push forward the group’s work. Seven years later, in 1988, AIDS Action Now (AAN) held its inaugural meeting in the same hall, using a similar agenda. Both meetings were chaired by Smith.

Like the RTPC, AAN’s steering committee was made up of many of the same old-timers plus a whole new group of women and men touched by AIDS. AAN organizers understood the power of public demonstration, but the RTPC experience also taught us the importance of solid research, lobbying, outreach and media work. And again, like the RTPC, AAN organizers were happy to spin off other organizations to meet specific needs. For example, both the Prisoners HIV/AIDS Support Action Network and CATIE, the Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange, began as AAN subcommittees.

The bath raids catalyzed the consolidation of the foundation of much of the Canadian gay community we now take for granted. Our response to the raids was training for a generation of activists who went on to build on this foundation in the fight against the AIDS epidemic and the long struggle for human rights and other legal recognitions.

Today, as the country, and some Canadian cities, slip back into the hands of the same kinds of politicians who found it expedient to loose the police on us in 1981, I can’t help but think that we may soon be called upon once again to employ those tools we started crafting in 1981.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra