Feb 5, 2016, is an important date for Toronto — 35 years ago, Toronto police raided the city’s gay bathhouses. More than 300 men were arrested, simply for being gay and open with their sexuality.

We remember this day not only for its infamy, but because this day in 1981 marks the time when gay men stood up and said they had had enough.

Over the next week, we will be looking back at that fateful day: at the activists who fought for their sexual freedom and continue the fight until this day; the homophobia and fear those men faced; and what we, as a country, need to learn from the bathhouse raids.

This article was originally published March 4, 2011.

The below are edited notes from a talk Ken Popert gave, organized by the Sexual Diversity Studies Students Union and delivered at the University of Toronto, on Feb 3, 2011.

Saturday, Feb 5, 2011, marks the 30th anniversary of the raids that ignited the Toronto bathhouse riots. And later this year, on Oct 27, Pink Triangle Press will be celebrating the 40th anniversary of the publication of the first issue of The Body Politic.

I’ve been asked to speak this evening on the role played by The Body Politic in that 1981 uprising.

I have to say at the outset that I’m not sure that I know the answer to that question. Cause and effect are hard to trace in politics. I have often had to reflect on that point because the mission statement of Pink Triangle Press requires me, as its executive director, to cause people to do something. It says (in part):

“The outcome that we seek is this: gay and lesbian people daring together to set love free.”

But people are not atoms. And journalism is not science. The role of The Body Politic in the bathhouse riots? I can offer only informed speculation.

And speaking of “gay and lesbian people,” I want to note that the terms that oppressed people use to refer to themselves are often in flux. Tonight I will be using the terms “gay” and “lesbian” because that is how the vast majority of the people involved in the events that concern us here described themselves.

Toronto’s heroic gay history

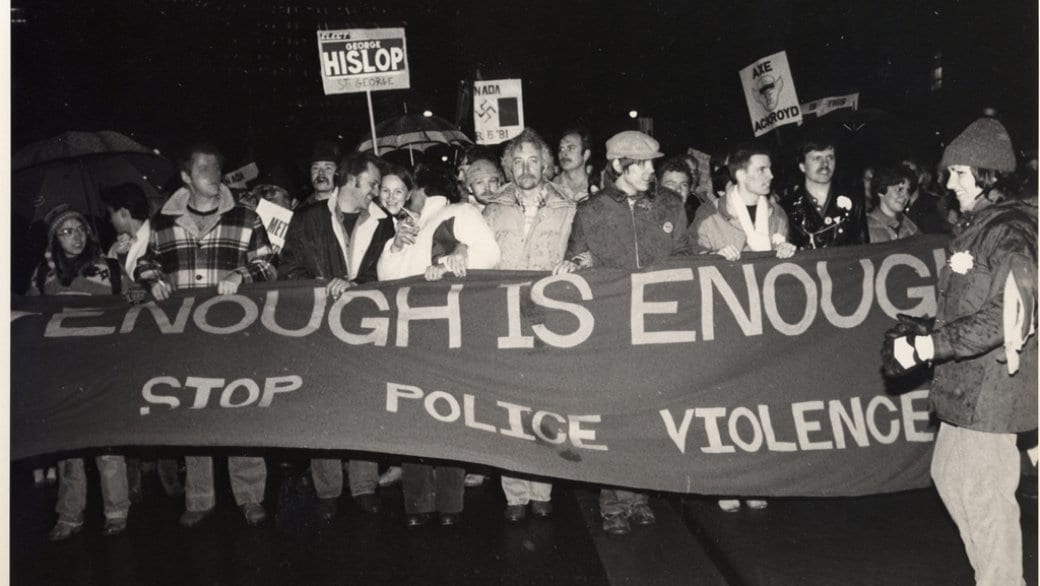

The Toronto bathhouse riots marked the beginning and the end of the heroic period of our history, five months of political unrest that began with the protest of Feb 6, 1981, and concluded with what I call “The Battle of Church Street” on June 20 of that year.

The simultaneous police raids in the late hours of Feb 5 on four of the city’s most popular gay bathhouse resulted in hundreds of arrests. Those raids are commonly described as the biggest mass arrest in Canada since the 1970 invocation of the War Measures Act. More significantly, they were the largest mass arrest within the living memories of Torontonians of the time.

Unlike the G20 police actions that we witnessed last summer, the raids produced an immediate backlash. Toronto, even some of official Toronto, was dismayed and horrified. Some city councillors and some media questioned the motive and the manner of this gratuitous intrusion into the sexual lives of gay men. A popular radio talk-show host warned his listeners that the raids had “created a polarization that will be a problem in Toronto for years to come.” A far-sighted man.

More importantly for us, these events transformed the gay and lesbian communities in this city. Toronto became one of just four cities in the world where gays and lesbians have risen up and physically confronted the authority of the state in the streets. (The others are New York, Montreal and San Francisco.)

Until the 1981 police onslaught, the reigning consensus of our communities was “Don’t rock the boat.” People behaved as if their relationship to society was governed by a social contract, the major term of which was that gays and lesbians would remain invisible and the state would leave them alone.

In this furtive, fearful, self-monitoring atmosphere, the surge of gay activism that had been born about 1970 in Toronto and that had begun to publicly challenge society and government was less than welcome in the very communities whose oppression it sought to address.

Throughout the ’70s, explicitly political activist groups were small, isolated and unsuccessful in building a mass movement. The example of gay pride celebrations is instructive: in 1974, five years after the decriminalization of homosexual acts, after four years of gay activism and with the example of Stonewall still fresh in every gay and lesbian memory, gay pride in Toronto could muster no more than about 200 people for a march from Allan Gardens to Queen’s Park.

In many of the succeeding years of that decade, there was no gay pride celebration at all. The most popular political cause that drew in more than a few dozen people was the unsuccessful campaign to elect George Hislop to city council in 1980, a project that, operating within the status quo, avoided political confrontation.

The bathhouse raids changed all that. Overnight, the Right to Privacy Committee, which had been a small activist group devoted to defending the sexual spaces of gay men, ballooned to a membership of about a thousand. Its first meeting after the raids had to be held in the auditorium of Jarvis Collegiate to accommodate the numbers.

The closeted, cautious social scene had merged with the public, confrontational activist milieu. A mass struggle for justice and freedom was on. A new consensus about our place in the city emerged and it continues to this day.

Out of the libraries & into the streets

The Body Politic was famously published by a collective, a shifting group of leading workers and decision-makers. The paper was founded in late 1971, near the beginning of that early wave of ’70s gay activism.

It was, in fact, partly the offspring of the activist group Toronto Gay Action. Like other such groups, the BP Collective was small and largely isolated from the communities to which and for which it wished to speak. But it had a singular advantage: it produced and circulated a publication that got into many hands and it had therefore — at least potentially — more influence than most other activist groups.

Nevertheless, early on many deemed it simplistic, strident and irrelevant to their lives. Collective member Gerald Hannon recounts that he sold TBP table to table in the Parkside Tavern, an important gay and lesbian social venue of the time. He recalls offering a copy to Mary Axton, a prominent figure in lesbian social circles: “No thanks,” she snapped. “I’ve got it memorized.”

So who was on the collective 30 years ago tonight, on the eve of the bathhouse riots? The masthead of the last issue published before those events records 13 collective members.

We were people much like most of you: young, informed and well-educated. Unlike most of you, we were finished with school but either unemployed or underemployed. At a glance, I recognize four who were class-conscious revolutionaries, about four liberals (in the 20th-century Canadian sense) and one possible libertarian. Others were harder to classify, but none would have counted themselves as conservatives, in any sense.

It was by no means a homogeneous group, and the paper itself was the product of an occasionally shifting alliance of agendas. This is reflected on its covers, where it serially described itself over the years as a newspaper, a journal and a magazine.

“Journal” was the favourite term of what I would call the academic faction of the collective. It viewed TBP as an instrument of comment and analysis, a homosexual riposte to the wider world.

Others were not content with simply putting opinions on pages. They saw the paper as a potential tool for political organization and wanted TBP to politicize its readers.

It was far from suited to such a task: a monthly — at best — it was poorly equipped to respond to developing events. And its circulation was constricted by a cover price: it was sold – much like Maclean’s is now — either on the shelves of bookstores or by subscription. Finally, it was not always an easy read; although it eventually achieved some very good graphic design, it always struggled to find an idiom that would engage a mass readership. At one of the paper’s several trials, an expert defence witness assured the court that TBP could do little harm to public morals because it demanded reading skills that most people didn’t possess.

Nevertheless, TBP was the best medium that anyone who wanted to influence gay opinion in Toronto had at that time, “the biggest gun in town” as collective member Ed Jackson used to say. And when Feb 5, 1981, arrived, it was ready to embrace the role of the agitating, propagandizing political newspaper that the new times demanded.

Fire-setter

In considering the role of TBP in the bathhouse riots, it is important to look more closely at the decade of the 1970s.

In those 10 years, Toronto’s gay and lesbian communities had steadily seeped out from underground. A handful of political organizations was gradually supplemented by a growing thicket of nominally apolitical community groups: sports leagues, choirs and so on. That growth can be easily observed in the fattening community listings that appeared every month in TBP, and the paper played an important role in encouraging that growth.

(I say these groups were nominally apolitical because they were, in fact, political in spite of themselves. Even in the late 1970s in Toronto, organizing a lesbian soccer club wasn’t the same as organizing a similar club for anyone else. Let me illustrate: in the late ’70s, a homophobic Toronto Sun columnist, Claire Hoy, led a campaign against what he called the “overuse” of the 519 Community Centre by gay groups. Just think about that: it was controversial that gay people were making use of a community centre located right in their midst to conduct the business of their community organizations.)

In helping this growing organizational network to flourish, TBP was also helping itself because the conjunction of an above-ground community with a regularly appearing publication created a novel thing in Toronto: a gay and lesbian public equipped with the tools to identify its problems and entertain solutions.

Now the solution that gay activists most insistently advocated was explicitly political organization and action. TBP played a large role in legitimizing and evangelizing such ideas. It backed this up with a stream of news and features, showing how gay politics was being pursued in Toronto and elsewhere. It covered the mass demonstration that followed a police raid on a Montreal bar. It pioneered the excavation of the lost history of gay struggle in early 20th-century Germany. The implication was clear: if they could do it, we can do it. Driving the point home, it reprinted in the masthead of every issue the famous 1921 dictum of German gay-rights activist Kurt Hiller: “The liberation of homosexuals can only be the work of homosexuals themselves.”

But, by the end of the 1970s, there was scant evidence that any large number of people were persuaded that activism was the way to change their lives and the world or indeed that anything needed changing. Even as the decade ended with a couple of small bathhouse raids that foreshadowed what was to come, few were concerned enough to do more than read about it.

And yet, I believe, something was happening. People did not, by and large, adopt TBP’s activist worldview as their own, but neither did they dismiss it. Instead, they tucked it away in some corner of their minds, out of sight but still within reach.

Then came the raids: their breadth and brutality shattered the common view that we were all right, that we could gradually progress, that we could quietly tip-toe our way to freedom and equality without a fight. Suddenly, people were looking for a new understanding of the world, one that made sense of the bathhouse raids. TBP had been laying down just such an understanding for almost a decade, and suddenly, in a flash, all those ideas about oppression, liberation and mass struggle made perfect sense. The activist moment had arrived.

Plumber

TBP’s second role in the bathhouse riots serves to remind us that even inspiring stories have uninspiring foundations. I refer to the unromantic subject of enabling infrastructure.

In 1981 Toronto, TBP was practically the only gay organization — political or otherwise — that had an address that wasn’t a post office box. It had an actual office, regularly staffed and equipped with telephones. And, as a publisher, it had the means of quickly creating and printing leaflets.

And when the mainstream media began calling around, it was TBP that had the phones and the staff to answer them.

Now, the word “office” may conjure up pictures of carpeting, matching furniture and the soothing rumble of an HVAC system. So let me explain that TBP’s offices at that time were on the fifth floor of a warehouse on the northwest corner of Duncan and Adelaide. The space had previously been used to store furs; consequently, it was only partially heated and had no air-conditioning; it could be an oven in summer and a freezer in winter. The bare wooden floors creaked with every step. It was underequipped, with mostly battered, second-hand furniture. I remember writers and editors arguing over who could use a desk and typewriter next.

Just hours after the raids, that office became the nerve centre of a frightened and angry community, freshly and brutally shaken out of its complacency, looking for leadership.

Amid all the confusion, what was probably the most important meeting in the history of Toronto’s lesbian and gay communities was convened there.

On the day following the raids, a hastily assembled group of about 10 people, representing TBP, the Right to Privacy Committee and the Metropolitan Community Church, met to decide what to do in this emergency.

Reflecting on the stubborn complacency that had always greeted our calls to political action, some thought the most we could do was muster an angry press conference and express our outrage, that a call to demonstrate would fail and reveal us to be leaders without followers.

Others felt that we could raise a decent demonstration, but that it would take a few weeks to win large numbers of people over to the idea of a mass protest.

Still others wanted to make a leap of faith and call for a mass demonstration on that very evening, just a few hours away.

(I was one of the people at that meeting and, although I feared the outcome, I felt that we had to go with a demonstration right away. This was a chance — perhaps the only chance there would ever be — for Toronto’s gay and lesbian people to experience the reality of their numbers and their power. I didn’t want to see it slip away.)

It was a tense, grim meeting. Adding to the pressure, outside the meeting room a big chunk of the city’s mainstream media was waiting to report what we planned to do.

I have described this as possibly the most important meeting in our history. Let me back that up by inviting you to consider what the place of our communities in this city would be now if options one or two had prevailed. The shared anger and resolve — the power — that was waiting to be summoned would have dribbled away, unknown and unexpressed. The authorities would have concluded that our communities, even when pressed to the wall, would not fight back. They would be able to go on treating us as they always had, perhaps worse — as the mass arrests already hinted — without fear of consequences.

I believe that we are sitting here in this room tonight because that leap of faith won the day. The meeting broke up, and a midnight demonstration at Yonge and Wellesley was announced to the waiting press.

Story-teller

The third important role that TBP played in the bathhouse riots was that of meaning-giver and story-teller. TBP took the inchoate mass of events that unrolled over a period of five months and extracted from it a narrative that encouraged, legitimized and recorded as our communities remade themselves into a lasting political presence in Toronto.

I said earlier that a monthly publication is poorly situated to perform this kind of political, activist journalism, but TBP managed to do a decent job, with a little luck, a little innovation and a huge helping of stubborn determination.

The luck came in the form of the timing of the bathhouse raids. They came near the end of the production cycle of the March issue of TBP, just before we were to go to press. With a great deal of help from concerned community members, we were able to get our version of what had happened — including Gerald Hannon’s gripping eye-witness account of the Feb 6 protest — onto the streets in just a week. Had the raids occurred a few days later, the March issue would have already gone to press, with the next not due for more than a month.

That issue, and the next two regular issues of TBP, began and continued the story of something new happening in Toronto: gays and lesbians fighting back. TBP gave evidence of the violence done to us, it brought our collective response alive on its pages, struck back at the cops, publishing the photos of police spies in our midst, posing as demonstrators, infiltrating and attempting to manipulate our newly powerful communities.

TBP ratified our struggle and made it real by putting it on paper.

The final, violent June 20 confrontation on Church Street, however, did not arrive on our schedule, so we had to innovate. Anxious to get our side of the story out, we threw ourselves into the creation of an entirely new publication — TBP Newsbreak — a four-page report that was conceived, produced and distributed free in clubs and bars within a couple of days after the events.

In just a few days, it delivered in words and pictures the evidence of the unprovoked violence that was visited on a peaceable protest by bashers and cops, apparently working in tandem.

* * *

Having planted the idea of rebellion and provided some of the means, during those anxious five months The Body Politic was always there, generating and ratifying the new understanding of our place in the world that the bathhouse riots demanded.

It was an understanding that we are entitled to be here and to live our lives in the open, that those lives are worth defending and that anyone who challenges Toronto’s gay men and lesbian women on that is in for a fight.

Just as important, TBP preserved a record of the great things that Toronto’s gay and lesbian people once did. Thanks to The Body Politic, we have the knowledge of what we accomplished when we acted together in those heroic months of 1981. And we can think that, what we did once, we can do again.

Ken Popert is the executive director of Pink Triangle Press.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra