Ontario resident? Need an expensive drug but can’t afford it? You can always apply to the Trillium Drug Program to get those costs covered.

If you want to know who to thank for that, you need to look back to a scruffy, rambunctious, angry bunch of New Yorkers, most of them queer, who in 1987, in the depths of the AIDS crisis, decided they weren’t going to take no for an answer. They set off shock waves felt around the world.

It was October 1987 when I bumped into Michael Lynch on College St. Michael and I had both been members of The Body Politic collective. He was American, regularly back and forth between Toronto and the great gay mecca, New York. “Have you heard about ACT UP?” he asked. I had, vaguely. “We have to do the same thing here. Will you come to a meeting at my place?”

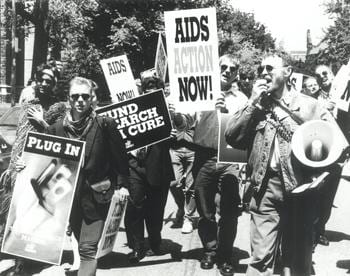

The result of those meetings was AIDS Action Now! We were just one of the many AIDS activist groups inspired by ACT UP NY, nearly 150 across the States, not to mention ACT UP Paris, other European incarnations and even South Africa’s Treatment Action Campaign.

I just finished watching United in Anger, Sarah Schulman and Jim Hubbard’s new documentary about the early days of ACT UP. It was emotionally draining. It took me back to a time I prefer to block out, when my friends, my fuckbuddies, the cute guys I cruised on Church St, all of us were suddenly dying. And the rest of the world didn’t notice. Or didn’t give a fuck. Or were terrified of us. Or said we deserved it.

We had little support, no information, no medicines, no hope, nothing but anger.

But what ACT UP did, and showed could be done with that anger, was nothing short of remarkable. They, we, made AIDS a political crisis and the world had to notice.

It’s funny what strikes you when you are looking at footage from the past. There is a brief scene in the film where people are putting away the chairs after a long and raucous ACT UP meeting. I flashed back to stacking those heavy, old, wooden fold-up tables at The 519 after every AAN! meeting. I remembered wondering how long I was going to be able to lift that much.

So much of AIDS activism was about meetings. In comparison with New York, our meetings in Toronto were quite restrained. We elected a steering committee to ensure the group was controlled by a poz majority. We elected co-chairs to manage things.

On the other hand, ACT UP’s regular general meetings every Monday night at the New York Lesbian and Gay Community Center could involve several hundred people. They were facilitated, not chaired. I attended at least one while visiting the city in the early ’90s. It was like a very large, unruly orchestra that hadn’t been tuned, with rotating conductors. But somehow it made music.

ACT UP brought together people with long political histories: gay liberationists, feminists, those with roots in the left and the civil rights movement, community organizers from poor neighbourhoods, sex-work advocates and others — the “blank slates,” those who had lived private, quiet, “normal” lives until they started getting sick.

To channel such diversity, ACT UP organized itself around affinity groups, like-minded people who wanted to do particular actions. If an affinity group needed resources and the support of the whole organization, that was thrashed out by the general meeting for however long it took.

In ACT UP affinity groups, ordinary people became experts: on AIDS, immunology and clinical trials; on media, graphic design and video production; on public speaking, banner dropping and civil disobedience.

ACT UP’s savvy use of media and images is still a model for political art today. It made Silence=Death iconic. The group pioneered the political funeral, and its activists scattered the ashes of loved ones on the lawn of an indifferent White House. They disrupted a mass at New York’s St Patrick’s Cathedral to protest the church’s stand against condoms. They zapped Dan Rather on CBS Evening News. They invented the “die-in” and blocked the streets in acts of civil disobedience. Footage of limp activists being dragged away by police became a staple of the public’s perception of AIDS.

True, ACT UP didn’t always play well with others. Early on there was a nasty name-calling war with New York’s biggest AIDS service organization, the Gay Men’s Health Crisis. They didn’t bother to let us Canadian activists know in advance that they planned to seize the stage at the Montreal International AIDS Conference in 1989. (But we did get to go along for the ride.) ACT UP figured its job was to be provocative, not popular.

While at first the concern was “getting drugs into bodies,” ACT UP quickly matured and developed a deeper analysis. It was not just a matter of generic individuals suffering from a virus who needed drugs. AIDS was a social problem. Racism, sexism, homophobia, poverty — all affected who got infected, who lived and who died. A criticism one sometimes hears of ACT UP was that it was just a bunch of entitled white boys. The powerful voices of women and ethnically diverse activists foregrounded in United in Anger give the lie to that notion. ACT UP took on the sexism of the drug-testing industry, which excluded women from trials; the racism of poverty and homelessness; the for-profit healthcare system that left the poor to die without treatment or care. When George Bush #1 launched his first invasion of Iraq, ACT UP filled the streets behind the banner “Money for AIDS Not for War.”

And today, as I’m writing this, ACT UP joined the Occupy movement to block Broadway at Wall St, demanding a financial speculation tax on stock market transactions to raise money to end the global epidemic and provide universal healthcare in the US.

And they did all this while continuing to be really sexy.

Which takes us back to the Trillium Program. While AAN! never developed civil disobedience to the high art ACT UP did in New York, we did disrupt question period in the provincial parliament. We chained ourselves to the furniture in the offices of the minister of health. We held massive die-ins at the Pride parade. We disrupted the NDP convention when Bob Rae was about to speak. And as a result, we won the Trillium Drug Program so that nobody in Ontario should have to get sick or die because they can’t afford medicine.

Without ACT UP’s example, I doubt that any of that would have happened.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra