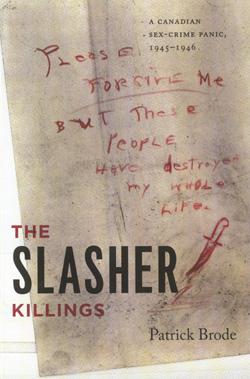

In the 1940s Ontario of Patrick Brode’s true-crime book, The Slasher Killings, Windsor was a mostly blue-collar town with a thriving demimonde of waterfront bars, flophouses and bordellos. The pre-war years of prohibition in the United States had made the city the go-to place for thirsty Detroiters from across the river. Postwar, with a huge Ford auto plant and the thriving Hiram Walker distillery, the city still had plenty of places for workers to drop fun money, while more genteel residents fretted about the evil going on down by the river.

Petty crime and drunkenness and the sex trade were the cops’ predictable obsessions, but the city had for years enjoyed a low murder rate. Then in 1945 “the Slasher” appeared. In the space of two summer weeks, three men were stabbed or beaten to death and a fourth sent to hospital with near-fatal wounds. A Windsor homicide inspector told a Toronto reporter they were looking for a Jack-the-Ripper style killer, “a sadist of the worst type, a maniac.”

In the absence of television and other media competition, Windsor’s prominent Star newspaper held a local monopoly on the news. With an editorial titled “This Fiend Must Be Caught,” they fuelled a growing sense of panic in their captive audience. The Slasher was a creature of “senseless blood-lust… with a perverted mind.”

Lacking suspects, police seemed to agree with the Star’s ensuing editorials suggesting the killer dwelled among “the riff-raff that congregate in certain undesirable sections of the community.” The force obligingly made a show of diligence by rounding up 125 homeless men and rooming-house residents. A month later the investigation was still stalled.

The murders had been gruesome. Two men had been stabbed repeatedly in the chest and back, one of them slashed brutally in the buttocks. The third had his head smashed to a pulp with a hammer. The Star fed public fears with sensational crime-scene photos, then printed a story falsely claiming that sex crimes were precipitously on the rise. “The juxtaposition with the Slasher attacks,” Brode writes, “made it appear as if it was all one vast contagion of crime.”

Then a hairdresser called the cops. According to Margo Hind, the Slasher’s targets were all “sex men” — her term for homosexuals. Hind told officers she had carefully studied the subject and believed that “85 percent of the big men in Detroit… managers etc, carry on this sort of practice.” She opined that the Slasher was a jealous lover offing his sex partners. The cops dismissed Hind as a flake, but then proceeded to put a queer spin on their investigation, essentially recycling her theory that both victims and perpetrator moved within the world of gay “sex perverts.”

A year after the third killing, two more men were similarly attacked but survived to tell their stories — which, along with more evidence from the earlier cases, confirmed that the victims were gay men. A suspect was identified. Eighteen-year-old Ronald Sears was arrested at his mother’s house. In the squad car he politely asked how long they might need him, as he was expected at “a wiener roast.” After some innocuous statements during interrogation, he went into confession mode, describing three of the murders, all similar in pattern: “We lay down in the weeds together and he unfastened his pants and began to jack me off. I told him to roll over on his stomach and I was going to put my cock up his rectum…. I had a hunting knife… and raised it as far as I could and had it poised to bring down where I thought his heart would be.”

Predictably, Sears’ arrest and the lurid details leaked to the press brought a new surge of moral panic. Community leaders urged mass detentions of all recognized “perverts.” One of the surviving victims found himself charged and convicted for committing the sex acts that preceded his stabbing, which he’d shared with the cops only to help convict Sears.

Brode’s book is filled with far more societal, legal and sexual tangents than it can adequately pursue in 200 pages. He squeezes in references to the laws of Tudor England, UFO reports, the bombing of Hiroshima and much more of dubious interest. A more detailed portrait of Ronald Sears — a deeply troubled, sexually ambivalent young man who described being sexually abused at age nine — might have made the book richer.

Still, the reminder of just how bad it was for queers only 60 years ago is sobering, all the more so because it’s so evident that homophobia still claims lives and queer love is still vilified. The virulent fears of Brode’s 1940s citizens and civic leaders weirdly echo the message coming from American pro-family lobby groups today — except now the phobes have slick PR budgets behind them. Patrick Brode’s vision of the bad old days disturbs precisely for how much it resonates in today’s climate.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra