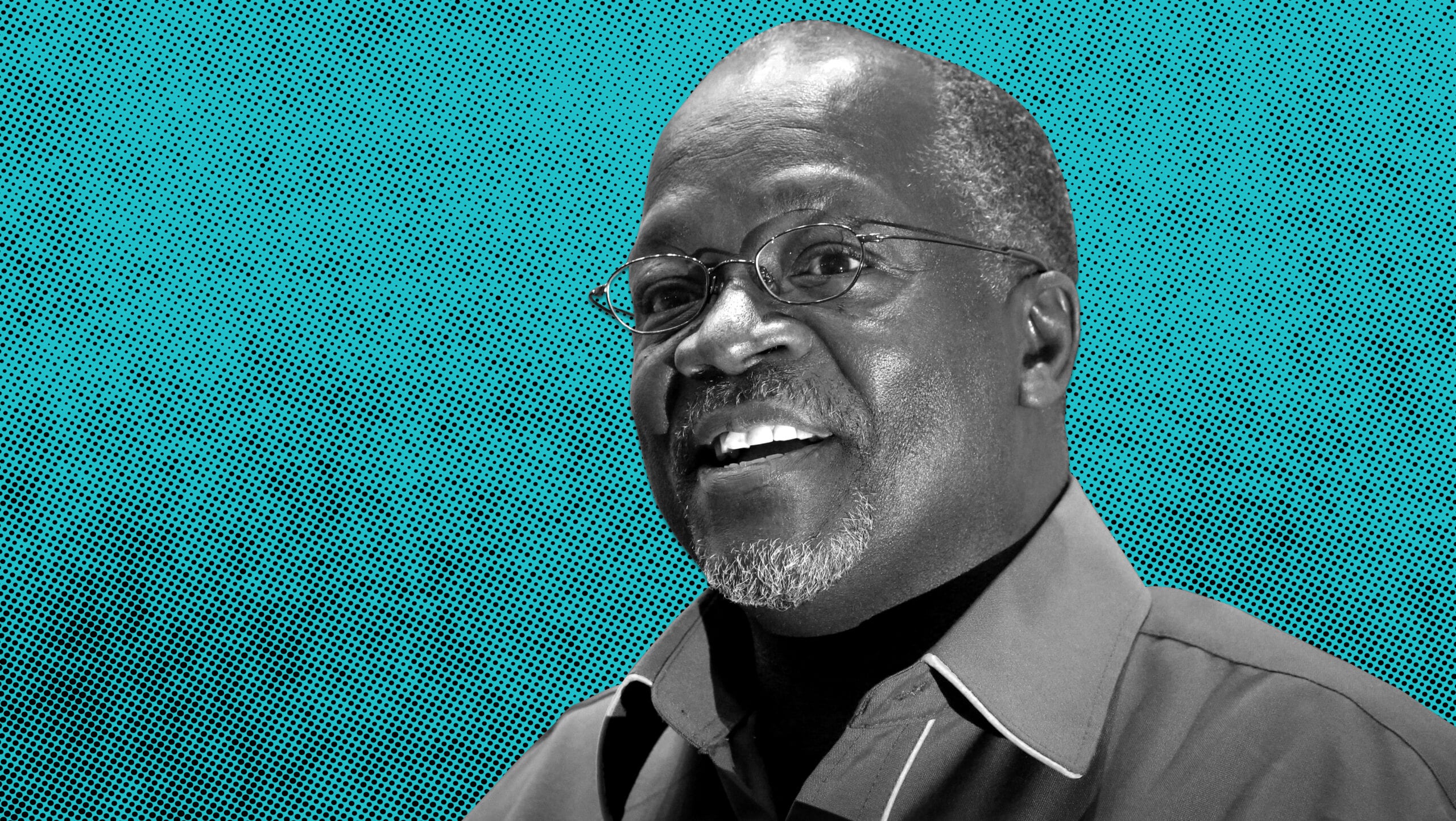

When James Wandera Ouma is asked what gives him hope as a gay man living in the east African nation of Tanzania, he can’t think of anything. “There’s no joy,” Ouma says. “There’s no happiness in life. You may have happiness in your own house, but when you go outside, you are afraid.”

Ouma is the executive director of LGBT Voice, one of just a handful of community advocacy groups operating in one of the world’s harshest countries for queer and trans people. In November 2018, Paul Makonda, the regional commissioner of Tanzania’s capital Dar Es Salaam, announced that authorities would begin rounding up individuals suspected to be LGBTQ. Same-sex intercourse is punishable by up to 30 years in prison in the country, and Makonda urged the public to report anyone they thought might be violating these laws.

The Tanzanian government walked back Makonda’s statements after condemnation from the World Bank, saying they reflected his “personal opinion.” But Ouma says the arrests never stopped. In the year and a half since, he knows of more than 30 people who have been arrested in mainland Tanzania and 20 people in Zanzibar. Ouma, who has been publicly out for 24 years, estimates that he has been arrested more than nine times throughout his life.

LGBTQ advocates and community members say life has gotten exponentially more difficult in Tanzania since the government began targeting queer and trans life four years ago. In June 2016, a news station in Tanzania aired an interview with a trans woman about her work with HIV prevention groups to distribute condoms and lubrication to local communities. Amina Mollel, a member of the country’s parliament, accused the station of violating Tanzania’s “morals and ethics by glorifying gayism.”

The government of newly-elected President John Magufuli responded by banning the operation of pro-LGBTQ organizations and ordering the closure of 40 drop-in centres that conducted HIV testing and distributed medication to people living with HIV. One of the key facets of that campaign was a ban on lubrication as a way to prevent gay men from engaging in anal sex.

Although HIV prevention organizations had successfully partnered with the Tanzanian government under previous administrations, Magufuli rationalized the new party line in an infamous speech claiming that “even cows disapprove” of homosexuality. His comments echoed similar remarks made earlier that year by Deputy Health Minister Hamisi Kigwangalla, who claimed LGBTQ people are “unnatural.” “Have you ever come across a gay goat or bird?” Kigwangalla tweeted. “Homosexuality is not biological.”

While Makonda upped the ante even further in November 2018 by encouraging Dar Es Salaam residents to turn in their LGBTQ friends and neighbours to authorities, he had been calling for such a campaign for years. Around the same time lawmakers began using TV broadcasts to stir up fear and hatred among Tanzania’s conservative, religious society—which is mainly divided between Christians and Muslims—Makonda claimed anyone who associates with a member of the LGBTQ community is “guilty” by association. Hinting at what was to come, he also pledged to use social media to hunt down LGBTQ people.

“If there’s a homosexual who has a Facebook account or with an Instagram account, all those who ‘follow’ him, it is very clear that they are just as guilty as the homosexual,” Makonda said.

“One queer safe house continues to get calls from LGBTQ people across Tanzania pleading for help. Many feel they have no choice but to flee the country altogether”

In a recent survey released by Human Rights Watch, the global advocacy group reported that the denial of care to Tanzania’s LGBTQ population has had a disastrous impact on people living with HIV. One individual said he had refrained from going to a government hospital for his medication in fear of discrimination, putting his own life in danger. While some HIV organizations have continued to operate underground, some are afraid to seek out these resources because of the possibility of arrest.

“I would like the government of Tanzania to allow [LGBTQ people] access to health services,” says Medard, a 38-year-old gay man. “If we don’t get services, we will die.”

It’s difficult to say why the Tanzanian government is suddenly so intent on targeting and stigmatizing LGBTQ communities. Adotei Akwei, the deputy director for advocacy and government relations for Amnesty International USA, says the growing intolerance is part of a “larger crackdown on fundamental human rights” under Magufuli’s administration, which has led to the arrest of journalists critical of his authoritarian regime and the closure of prominent media organizations.

Each of these attacks on the civil rights of Tanzanians, which includes newly passed restrictions on laws permitting freedom of assembly, play into each other. “Everyday citizens who don’t speak up for LGBTQ communities don’t seem to realize that that’s the danger,” Awkei says. “Today it might be the LGBTQ community, and tomorrow it might be human rights defenders. If you don’t protect one community, you protect none of them.”

Despite the increasing persecution by government officials, LGBTQ people say the worst threats to their health and safety are not from authorities but from those emboldened by their rhetoric. Wenty, a longtime LGBTQ activist in Tanzania, says a gay man came to him in the middle of the night after he was evicted by his landlord. The property owner said if he didn’t get out immediately, he would invite the man’s neighbours to come over and attack him.

“He had to run,” Wenty recalls. “He came to my house and he told me, ‘They wanted to beat me,’ so he left everything there.”

These cases are extremely common, Wenty says. In addition to providing temporary refuge for several individuals in his own home, he operates a safe house funded by the international human rights group All Out. When the shelter first opened last June, the demand was well over capacity. It was designed to house between 10 to 15 people in a month, but was servicing the needs of as many as 22 individuals—many who were often forced to share mattresses in already close quarters.

Things have slowed down in the year since. Speaking over the phone, Wenty says that seven people were staying at the safe house in late February but noted that they continue to get calls from LGBTQ people across Tanzania pleading for help. Many feel they have no choice but to flee the country altogether.

“I feel sorry for what we are going through,” he says. “I feel like if I am not doing [something about it], then someone else will suffer. I don’t want them to go through what I’ve gone through.”

“There doesn’t appear to be an end in sight: Other African nations have launched their own attacks on LGBTQ life”

Although Wenty is applying for funding to expand the safe house’s programming, there doesn’t appear to be an end in sight: Other African nations have launched their own attacks on LGBTQ life, including Egypt, Nigeria, Uganda and Zambia. Gabon, which did not have a colonial-era law on the books banning sodomy like many of its neighbouring countries, passed a law in 2019 criminalizing same-sex activity for the first time. Many of the laws penalizing same-sex intercourse in Africa were passed under British and French rule during the 19th century and were never removed from the criminal code.

But there are some bright spots. Same-sex marriage has been legal in South Africa since 2006, while Mozambique’s employment laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Last year, Botswana became the only African country to ever overturn its criminal codes banning same-sex relations. While Kenya’s high court upheld its anti-sodomy laws just days before that groundbreaking ruling, the government rolled out a question about intersex status in the national census, making it the first on the continent to count its intersex population.

“That’s huge because being counted means being recognized,” says Daina Ruduša, senior communications manager for the LGBTQ non-profit OutRight Action International.

While advocacy groups say international pressure—such as the U.S. government’s recent decision to ban Makonda from entering the country—could help to improve the lives of LGBTQ Tanzanians, many feel the targeting is unlikely to cease anytime soon. Magufuli is up for reelection in 2020, and Wenty says he is likely to use LGBTQ communities as a wedge issue to increase his support. Even though Tanzania is facing bigger problems, like lack of access to clean water and extremely high rates of poverty, he says it’s an issue that “really captures people’s attention.”

“Because Makondo got so famous out of it, we assume other politicians might use the same strategy,” Wenty says. “We are prepared for it.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra