When

I first met GB Jones, well over a decade ago, she was overachieving madly:

playing in Toronto’s seminal all-girl punk band Fifth Column; making Super 8

movies with the deadly earnest yet tongue-in-cheek aim of inciting a juvenile

delinquent revolution; co-publishing JDs, arguably the most important queer

zine ever; and launching what came to be called “homocore,” laying the

foundation for just about anything we now call, for desperate want of an

elegant term, “alternaqueer.”

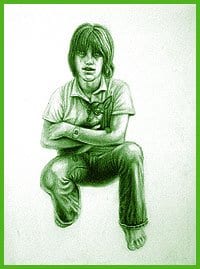

Around that time, Jones began to produce a series of illustrations called

Tomgirls, clever and funny re-creations of Tom Of Finland drawings – his

bulbous, over-developed male bodies replaced by her curvaceous, over-developed

female ones. These were, at times, overtly political. Tom’s well-known “I Am A

Thief” series, for example, becomes “I Am A Fascist Pig” in Jones’s hands. It

evoked another self-evident, politically-charged message through the placement

of the perversely sexualized female bodies in a space “reserved” for the male.

But most interesting is that the Tomgirls are more often than not women with

whom Jones was acquainted: These works are in fact portraits, a tradition she

continues to explore. And “tradition” is very much the key word. The artist has

no truck with the “kill your idols” impulse. The erosion of traditions –

cultural, aesthetic, artistic and even linguistic – greatly concerns her, as

its effect is the loss of valuable foundations. Somewhat hyperbolically, she

claims that the artistic movements of the 20th-century are little more than a

series of vanity projects – an ever-diminishing attempt at the shock of the

new. Instead, much of her inspiration flows from portraits from around the turn

of the 19th-century.

“I have certain formalist ideas about portraiture,” says Jones. “One has to

think about the subject, what kind of meaning the portrait invites.” In short,

the artist is accountable for the presentation – and to some degree the

reception – of the image produced. She’s looking at the difference between

respect on the one hand, and exploitation on the other.

In a clever move, Jones collapses traditions in her current work, uncovering a

new set of issues. A recent piece featured a wall of pencil portraits, each

flanked by drawings of lollipops. The drawings feature “a cross-section of

people who are in my movie, The Lollipop Generation, playing underage porn

stars – people who really were underage porn stars.” Jones points out that the

drawings of the latter – among them Traci Lords and Peter Gladstone – are all

based on pictures taken after they had turned 18.

“I don’t want to exploit people who are in that situation,” Jones says. “I

don’t want to take away the power they have.” It’s a delicate balance, and one

that takes careful consideration. Another of Jones’s recent works – a portrait

of kidnapping victim Steven Stayner and his dog Queenie – is currently in a

show at the Paul Petro Gallery.

When these exploitative situations come to light, the result is hysteria. “The

problem with that is that these people [the purported victims] become

invisible,” eclipsed by the outraged posturing of those claiming to champion

their rights. “So while it’s true that they are in a circumstance where they

are victimized, in a way their invisibility perpetuates that.”

The act of creating portraits gives her subjects visibility, but the respect

inherent in that same act invests them with accountability. No longer mere

indices of a societal hot button, they appear as people who have made choices

that, for better or worse, led them where they are. Thus Jones exposes complex

questions around the responsibility of – and for – what we dismissively call

“the juvenile delinquent.”

She illustrates with the story of Jeff Browning, the porn star who, after

appearing in a whole whack of videos, threw himself an 18th birthday party.

Where, Jones asks, does the responsibility for Browning’s actions lie? It was

suggested Browning should take the rap for his dupe. “But there’s a big

contradiction there,” says Jones. “You’re saying, ‘This person was underage and

a victim,’ and yet totally responsible for their behaviour. Which is it going

to be?”

This kind of contradiction negates Jones’s subjects’ powerto choose – a power

her portraits, to some degree, respectfully reinstate. Re-arming the

disenfranchised would seem a lofty task, but Jones is unwilling to overstate

her influence: “I think I’m in a position to have a nominal effect on the

culture, so I exercise that.”

* Paul Petro’s summer group show continues until Sat, Jul 26. In November, GB

Jones will have more new works, featuring car crashes and other accidents, in a

joint show with Paul P, also at Paul Petro Gallery (980 Queen St W); call (416)

979-7874.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra