While more professional athletes have come out of the closet in the past year than in the past decade, an expert on homophobia in professional sports says it is still the last great bastion of institutionalized homophobia.

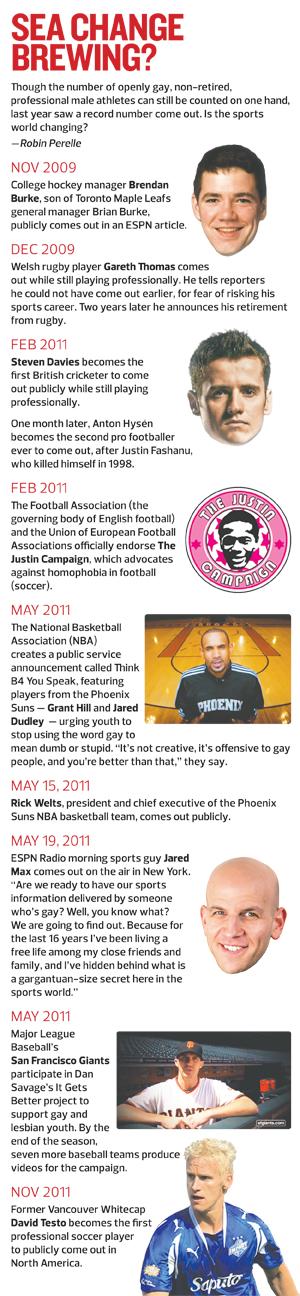

In 2011, dozens of athletes publicly came out across a spectrum of disciplines, ranging from swimming to cycling to soccer. Momentum gathered as several high-profile organizational figures — such as Phoenix Suns president Rick Welts and ESPN radio host Jared Max — followed suit, and straight allies like wrestler Hudson Taylor, of the Athlete Ally foundation, and rugby player Ben Cohen, who founded the StandUp Foundation, helped put the anti-homophobia message on the international agenda.

The same year, Major League Baseball got involved at the franchise level when the San Francisco Giants participated in Dan Savage’s It Gets Better project, and by the end of the season a total of eight MLB teams had produced videos for the campaign.

Former basketballer Charles Barkley was vocal in his condemnation of homophobia in sports, and the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network ran its Think B4 You Speak campaign on television during a National Basketball Association game in May.

Gains were made even in the world of soccer, which has been heavily criticized for its lack of organizational support for an anti-homophobia strategy. In 2011, the United Kingdom’s The Justin Campaign, which advocates against homophobia in the sport, secured official endorsements from both The Football Association and the Union of European Football Associations.

Indeed, if a spectator dropped in for the 2011 sports season only, it seems likely that he or she might conclude that homophobia in sport is an antiquated issue, a throwback to a different, less enlightened time.

But according to Caroline Fusco, an associate professor in the Faculty of Kinesiology and Physical Education at the University of Toronto, professional sport remains a stronghold of homophobic attitudes.

“Sport as a space has been one that has really been there for the production of a certain kind of hyper-masculinity. Particularly when you think of pro sports, the big ones: hockey, football, baseball. These all tie in to the rugged notion of masculinity, and these attitudes remain — that gay men aren’t masculine,” she says.

Strategies like Brian and Patrick Burke’s You Can Play campaign, which is aimed at the National Hockey League, are trying to change that. Advocates go after the highest-profile names they can secure to create messaging that challenges that notion.

It’s an effective method. The events of 2011 seem to suggest a sea change in the sporting culture. But is the endorsement or coming out of a collection of high-profile sports figures a reasonable measure of the state of homophobia in sport? Is it the best way to tackle homophobia?

Marc Naimark, vice-president of external affairs for the Federation of Gay Games (FGG), seems to think not. “The Federation of Gay Games [has] continued to offer opportunities for LGBT athletes to be active in sport in a safe environment while engaging straight athletes in clubs or at sports competitions,” he says. “When we consider sheer numbers, that is far more significant than the elusive out pro athlete.”

This may be true, but it’s the story of that single athlete — not the thousands of competitors who participate in the Gay Games or the Outgames or any of the numerous single-sport tournaments that take place annually around the globe — that interests mainstream media. The story’s got to be sensational, and even then, there may be some resistance to the subject .

Earlier this year, CBC sportscaster Ron MacLean told Xtra he’d been “taken to task” by the CBC and The Globe and Mail for broaching the subject of gays in sport. The conversation was in reference to out former Olympian Mark Tewksbury, which in turn was in reference to the Beijing Olympics.

“The media, of course, are really always thinking about their audience and money, and if talking about gays in sport hurts sales, then that’s going to cause some concern,” Fusco says, adding that the mainstream media generally have conservative values.

Sportsnet writer Stephen Brunt says he hasn’t had an editor reject a sports story with a queer angle but conceded that he had been fortunate to work with a progressive selection of outlets.

But whatever the truth is about representation in the media in Canada, it’s not a global measure.

FGG communications committee volunteer Kelly Stevens says the sports world is moving from tolerant to supportive in parts of the world. “This is not global,” he says. “Many nations have bias and poor treatment of gay and lesbian people, including athletes.”

There has been remarkable progress in European countries like Germany, Sweden, the United Kingdom and in Canada. But what about athletes from the developing world? Does the fact that English wicket-keeper Steven Davies chose 2011 to become the first out cricketer make a difference to a gay athlete from Senegal, for example?

“Homophobia is also tied in to social class, to race as well,” says Fusco. “Who gets this hyper proving ground for masculinity?”

This is not to suggest that the actions of high-profile athletes do not matter; they certainly do. But something’s missing in the model. According to Fusco, anti-homophobia campaigns need to take a more holistic approach.

“These campaigns are really important, [but] there’s something about the implementation of the plan. It starts very early for boys and girls, at school, and schools need to be involved. Municipal, provincial and federal governments need to get on board.

“And as for that athlete in Senegal, I think if the Canadian Olympic Committee really took on human rights, including sexuality . . . I think with international competitions, there’s so much travel across the world. We have a responsibility.”

Below is a selection of videos Xtra has done on homophobia in sport.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra