In the 1950s the intersection of Elizabeth and Dundas streets was one of the roughest parts of downtown Toronto. Known as The Corners, it was a dense point on the map of the city’s underworld where prostitutes, drug dealers and gamblers congregated.

The neighbourhood had little to recommend, yet every night for almost 20 years, women from all over the province came here looking for sex, love, and in some cases, a life partner – which in those days could sometimes be consummated with an illicitly obtained marriage licence.

As in countless other North American cities, a working-class lesbian bar culture took shape in Toronto after the Second World War, and the Continental Hotel had one of the few non-discriminating beverage rooms.

Notoriously dingy and filthy, it was a haven for whores, pimps, johns, transvestites and a handful of local Chinese and white working-class male residents. Regulars affectionately called it “the pit.” Most women took heed of the bathroom graffiti – “Don’t sit on the toilet seat, the crabs here jump 50 feet” – and relieved themselves in the rest rooms across the street. Still, the Continental was nirvana for women who preferred their own kind.

Lynn C (to protect confidentiality, last names are not used), now a lesbian grandmother employed in the social services sector, vividly remembers her first trip to a gay bar in the early ’60s when she was a mere 17 years old: “I was in my glory. It was like my life just started, like life really meant something to me all of a sudden. I thought I had come across some place better than earth.”

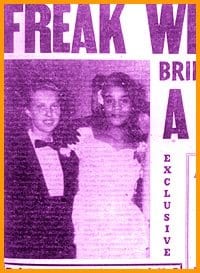

After the first blush of excitement wore off, many of the Continental regulars began a long and arduous search for love. In 1956, Geraldine and Ivy were convinced they had found it, and they decided to get married. Donning a simple white dress, Gerry looked the perfect bride beside her grinning, tuxedoed groom. Toronto tabloid Hush declared the event a freak wedding because the bridegroom was a girl, never mind that they were an interracial couple.

But for Continental regulars, known to each other as “downtowners,” there was nothing freakish about gay weddings. According to Eileen M, a retired registered nurse whose first career was turning tricks on The Corners in the ’50s, as many as 20 percent of lesbian couples she knew at the time had some sort of a marriage ceremony.

For the truly brave, the process began with an application for a marriage licence, an act that required the groom to pass as a man in front of government officials.

Passing has a long history. In 1856, 15-year-old Canadian-born Sarah Emma Edmondson changed her name to Franklin Thompson to escape her betrothal to a local farmer. As a man living in Victorian Canada, Edmondson travelled much more freely as Thompson than she ever could have as Sarah.

Not all women who passed made their sexual inclinations known, but Thompson had great difficulty keeping away from the ladies. Thompson invited scandal when, employed as a male nurse during the American Civil War, he carried on an affair with the chaplain’s wife. Though Thompson never took a wife of his own, he threatened to, and many of his contemporaries in fact did, their true sex revealed only after death.

Getting a decent paying job as a woman was much easier in 1956 than in 1856, and urban lesbians used their gender identities in a strategically different manner, dressing as typically female in the work world and dressing butch in the nighttime and on weekends. Unsuspecting City Hall employees issued more than a few wedding licences to Paulines passing as Pauls, but Toronto civil servants weren’t the only ones who got the gender slip.

African-American women in pre-World War II Harlem successfully obtained marriage licences this way, as did at least one couple in Paris. Using forged documents, a French lesbian couple were legally married in 1961, though the groom was later charged with fraud. In rendering his sentence, the judge ominously warned that the man whose name the couple had used as husband had the legal right to claim his full marital privileges.

Post-WWII lesbian weddings were shaped by the same constraints faced by any other working class couple. Money and resources determined the scope and size of the event, but it usually involved all the standard trappings: invitations, rings, cake, band, hall, bridesmaids and lots of drinking and dancing. One Continental regular described a downtown wedding as “a real wing-ding” complete with fancy clothes, limousines and a hired band, all extravagant luxuries for women on The Corners.

Eileen remembers some weddings so big “that even the [beat] cops [from the Corners] would go.”

In the tabloid coverage of Ivy and Geraldine’s big day, the reporter feigned disbelief that the presiding minister, an ordained man of the cloth, was fooled into thinking that the bride and groom were man and woman:

“Even dim lighting or poor eyesight could not conceal the obvious fact that the bride seemed considerably more masculine in appearance than the effeminate looking groom. And despite the size of the best man, the mannish haircut and suit of tails, the swirl of the hips beneath the trousers, and the generous bulge under the white dickey front, was sufficient to suggest that somewhere along the way, sexes had been switched, or a sincere attempt was being made to infer that such was the case.”

As the writer suggests, even the most naïve minister would have quickly spotted the ruse. But perhaps even the intrepid reporter was not aware that plenty of ordained ministers were friendly to lesbians and gay men, and regularly performed marriage rituals or covenants. So common were these ceremonies that, according to Laurentian University historian Gary Kinsman, in 1964 the United Church banned its ministers from conducting them. The Catholic Church followed suit shortly thereafter.

You didn’t have to go to Rome to meet with disapproval. Plenty of gay men and lesbians shunned queer nuptials, claiming that the butches and queens who openly flaunted their homosexuality and made a mockery of sacred institutions gave homosexuals a bad name (a much different spin than the gay conscientious objectors around today, who accuse those who want to get married of aping the mainstream).

The Ladder, one of the first lesbian magazines published in the US, well reflected the older view, suggesting it was unwise to flout convention. “Let us keep our private lives as personal as can be,” implored one reader.

But those weddings were usually an earnest, open and public declaration of love and commitment. Vows were worn like a talisman to ward off sexual competitors.

“The ones that got married, to them it was official,” says Eileen. “They believed in their hearts they were truly married. It’s faith, girl.”

Not that marriage always settled things. A California University student’s 1968 report on a wedding ceremony for two white, working-class women officiated by an African-American gay ex minister of the Church Of Faith And Deliverance includes a description of the newleyweds’ first spat. In the post-ceremony celebration at a local gay bar, the groom’s tempered flared when the bride accepted one too many invitations to dance from an old admirer. Friends interceded, and the party continued.

Two years after she exchanged vows with Ivy, Geraldine was back in the news, though this time sporting a different girlfriend. In true tabloid style aimed at suggesting lesbians couldn’t have stable relationships, Hush gloated that “bride Geraldine was soon back in her favourite haunts billing and cooing with other females of the cult.”

Eileen offers a more meaningful explanation. Years of personal observation and experience taught the downtown crowd that the only way to survive as a couple was to leave The Corners for good, to “kick over the traces” as lesbians and re-emerge in the newly developed suburbs as unsexed female friends and roommates.

Leaving the bar scene was a tough choice that meant living without the support of other couples, and the camaraderie of friends, never mind the fun of staying out late on a Friday night. Few women, especially young ones like Gerry and Ivy, were willing or ready to make that sacrifice.

When the gay liberation movement exploded in 1968, it marked the end of an era, including passing for lesbian women. Less well known is that the right to marry was one of the first public battles homosexuals fought. A gay librarian whose job offer was revoked by a Minnesota university when he applied for a marriage licence with his lover ended up at a US federal human rights hearing in 1970. The complainant lost, as anti-discrimination laws, the federal tribunal concluded, did not extend protection to homosexuals.

Shortly after, the US delegate to the United Nations Human Rights Commission, Rita E Hauser, spoke at an American Bar Association convention where she publicly declared discrimination against gay and lesbian marriage unsustainable.

Opposition to state-sanctioned homosexual marriage was formidable, but the struggle was abandoned as gay liberation became more closely aligned with Marxism and lesbians with feminism. Marriage was discarded as one of the most egregious manifestations of a patriarchal bourgeois society, and the struggle for marital rights was renounced.

Still, the tradition of lesbian and gay weddings continued unabated, though now homosexual couples in some of North America’s bigger cities had their very own church and ministers to perform them.

In 1973, the gay-positive Metropolitan Community Church established its first Canadian congregation in downtown Toronto under the leadership of Rev Bob Wolfe. In his first two years, Wolfe presided over more than 20 holy unions.

“Straight people get married when they’re in love. Why shouldn’t we?” said Nancy, one of Wolfe’s early newlyweds. “I think we’ll have a wonderful marriage.”

While not all gay and lesbian couples seek to have a holy or civil union, the determination of those in love to find ways to show it through marriage extends much further back into history than we might have imagined.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra