Barely a minute into meeting Danny Grossman, he hands over a stack of photocopied papers.

“I think you should read this,” he says, referring to press articles on the subject of gay marriages and the church. “Clinton Backs Bill Restricting Gay Marriages,” goes one headline. “Desmond Tutu Blasts Churches,” reads another.

Seconds later, he digs out Denis Joffre’s set and costume designs for Passion Symphony. And before I even get the chance to press the record button on my tape recorder, he’s well on his way to a heated discussion of Passion Symphony’s premise: gay marriage and the church.

This remount – it premiered in 1998 – is the centre piece of his much-anticipated program at Buddies In Bad Times Theatre next week and is clearly a project close to Grossman’s heart and mind.

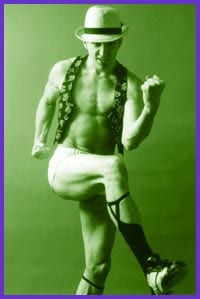

For the uninitiated, Grossman’s excitement and passion for his work can be staggering. It helps to remember that he’s not just another choreographer and dancer around town. This is a man who has helped shape modern dance as we know it today in Toronto and English Canada. Along the way, he’s also picked up the reputation for being dance’s political animal.

To steal the title of Mark Franko’s seminal study of modern dance, Grossman is dancing modern but performing politics. Visit his website and you’ll be forgiven for thinking you’ve stumbled into the official site of the French Revolution. Words like equality and social responsibility appear almost as frequently as dance or choreography.

“It’s my gift, I’m a storyteller – a narrative choreographer,” says Grossman. “I’ve always had the strength in my work to make the statement I wanted to make.”

Perhaps Grossman’s dance with politics was preordained. He grew up in a radical household in California of the late 1950s and early ’60s – after the beats and just before the hippies – and came to full maturity in New York in the mid ’60s as a dancer for the legendary Paul Taylor.

In 1973 he moved to here to join the Toronto Dance Theatre, then a five-year-old phenomenon. Virtually every dance he’s choreographed since has been inspired by a political moment or event in his life.

Sexual and gay politics have been at the forefront. Higher, his 1975 breakthrough number, was a sexual-acrobatic act performed by a man and a woman with two chairs and a ladder. Set to the soul music of Ray Charles, Higher was a stunning introduction of things to come and remains one of Grossman’s signature numbers. Its success convinced Grossman that he had what it takes to form his own company. In 1977 the Danny Grossman Company was established in Toronto.

“There was money then,” Grossman recalls those long-gone days when funding for dance and the arts in the province was at its peak. “I did make a splash because I was new and different.”

In 1981’s Nobody’s Business (which opens the Buddies’ program), Grossman returned to the realms of sexual politics. This satirical look at gender role reversal with its ragtime music is Grossman through and through: a high sense of the theatric and the athletic is mixed with irreverent humour.

Women, dressed in pants and bras, show off their athletic prowess and lift their effeminate male partners. The middle section is a duet for two men to the lyrics of “T’Aint Nobody’s Business If I Do.” The men kiss, fight and make up on stage in this “younger work,” as Grossman describes it.

“I’m probably more out of the closet now than I was when I choreographed Nobody’s Business,” says Grossman. “Now that I’m older and can understand the dimensions of the whole situation. I choreograph the repressed – which is Passion Symphony.”

Paradox or natural progression, Passion Symphony marks his return to a more explicit gay subject matter. It was born at a highly introspective moment in Grossman’s career. “I was doing it in an age when I can look back and realize that I’m still angry,” he says.

Passion Symphony is a disturbing work about a doomed relationship between a young gay man and his priest.

“In the beginning I thought of it as a more politically funny piece,” says Grossman about an earlier version, with a rhythm and blues score and a raucous, Queer Nation-style wedding. “It didn’t really work until I changed the music and realized that the most important part was the relationship between the two men.”

The crucifixion movement of classical composer Marcel Dupré’s Passion Symphony unlocked the piece and it became both a study of the devastating effects of sexual repression and a quest for enlightenment.

“Because the priest is not at home with his sexuality,” Grossman continues, “he’s the one who journeys out to investigate outside the relationship. At first I thought it would be a ménage-a-trois, and it is. But the two he’s relating to are angelic forces,” referring to Paul DeAdder and Philippe Dubuc’s pivotal turns as the priest’s guiding angels.

“You’re able to transcend their times, their condition and their profession,” dancer Gerald Michaud, who takes on the priest role, says of the lovers, “to bring these two characters into a glorified union.”

Watching Michaud and Grossman taking turns explaining Passion Symphony, it suddenly hits you that there’s a strong psychic bond and a sense of camaraderie between the two. If they don’t exactly finish each other’s sentences, they are at least on the same wavelength.

Members of Toronto’s dance community envy Grossman his ability to create such close, personal and creative relationships with his dancers and staff. “We still like and love each other,” insists Michaud, who has been with the company for nine years. “This is our day off and we’re going to have dinner together.”

“We don’t have better friends,” adds Grossman. “We have parents, we have lovers, but we don’t have any better friends.”

Grossman’s larger project extends beyond the artistic direction. He is working towards building a community for dancers and other like-minded spirits. His is one of the few dance companies in Canada that have shown unwavering support for community-based work.

“We’re not just interpreters of [Danny’s] work,” says Michaud, “we’re also carrying the torch with him, sharing and co-creating.”

And in an effort to ensure that future generations experience the work of modern dance pioneers, the Danny Grossman Company actively preserves older dances by integrating them into its repertoire.

“To learn more about dance, you have to see its history,” says Grossman.

But if it all sounds like the plans of someone who’s approaching the end of a career and is looking at his past glory, think again. Physically, his body may fail him, but there’s no stopping Grossman’s choreographic flow.

“I much prefer making a new dance if I’m not trying to stay dancing,” Grossman says. “It takes $1000 a week to maintain this body for dancing and that’s just foolish.

“I’ve always been very realistic and not hanging on to stuff,” he adds with a very calm tone. “I don’t know how long it’ll be.

“A lot of the pioneers have stopped choreographing or no longer have companies.” Pause. Silence. “Martha Graham went on until she was 96 and still had a company.”

A simple calculation means that we can expect 38 more years of Grossman’s politically charged choreography. Even if he falls short of Graham’s record, Danny Grossman’s legacy will live on.

Passion Symphony.

$13. 8pm.

Wed, Mar 1-4.

Buddies In Bad Times Theatre.

12 Alexander St.

(416) 975-8555.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra