Svend Robinson’s public coming out didn’t go according to plan.

News leaked early and the fallout hit his riding in Burnaby, BC, like a ton of bricks.

“Someone smashed my office to bits,” Robinson recalls. “So I did a press conference in the broken glass, to show that this is the kind of violence people are subjected to.”

Two days after the vandalism at his office, Robinson made his official announcement. In characteristic style, he did it on national television.

“I’m a member of Parliament who happens to be gay,” he told Barbara Frum on CBC’s The Journal. While Robinson was hardly a closeted man, he had never discussed his sexuality with the media.

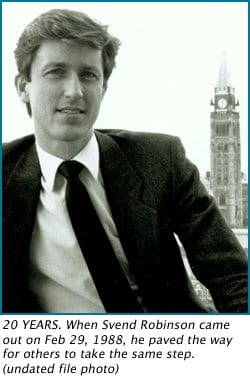

That was Feb 29, 1988 — he became Canada’s first out gay federal politician.

At the time, Saskatchewan premier Grant Devine said he had as much compassion for bank robbers as homosexuals. BC premier Bill Vander Zalm said he would be very concerned if anyone from his caucus or cabinet came out as gay. Chuck Cook, a Conservative MP from a neighbouring riding, said a major election issue would be whether people thought a self-confessed homosexual was an appropriate role model for their children. Robinson was ridiculed by Brian Mulroney and others.

Ask Robinson about it now and he’ll tell you he’d like to think of it as a non-issue — one that should be irrelevant.

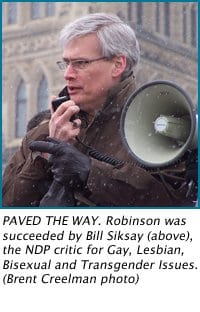

But it paved the way for others to take the same step, and for a change in the mindset of the Canadian public, says Bill Siksay, the NDP critic for Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender issues. He worked with Robinson for 18 years and succeeded him in the riding of Burnaby-Douglas, where he also ran as an out gay man.

“It was a huge step for a Canadian politician to take at the time,” Siksay says. “and it was a pivotal moment in gay and lesbian history in Canada.”

Some Canadian politicians at the local level had come out before Robinson. But as the first to do so in federal politics, he gave new prominence to its openness.

By 1988, Robinson had been working for gay rights in Parliament for almost a decade. Siksay says Robinson’s coming out put a human face on the issues.

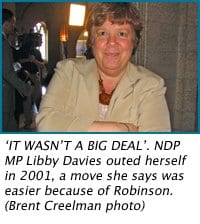

New Democrat MP Libby Davies says debates in Parliament can be very personal. People bring their own experiences to the table when discussing the issues, so having a diversity of voices on the Hill is important. When Robinson asked her to comment on same-sex marriage in 2001, Davies not only gave a speech, but also outed herself as a lesbian.

“People were talking about their own relationships, and I thought, well, I’m going to say something,” Davies says of her impromptu announcement.

It wasn’t all smooth sailing for Davies. She describes the media onslaught that faced her in the lobby of the House of Commons that day, and remembers a headline the following morning that read: “Davies admits gay relationship.” She was outraged, she says, because it implied that she had confessed to some sort of wrongdoing. It also highlighted the importance of language in dealing with issues of diversity. Still, she says her coming out was easier because of Robinson.

“I felt like it shouldn’t be a big deal. Although for Svend, it was. He really paved the way so that it wasn’t a big deal for someone like me.”

Incredulous that a public figure would come out willingly, Robinson recalls that the media made attempts to explain his actions. These included speculation that he had AIDS, and another suggestion that he had carried on a torrid love affair with a Liberal cabinet minister, which was about to be exposed.

Even sympathetic voices in the media were skeptical about his chances for coming out of the closet with his political career intact. Just before the announcement, an article in the Vancouver Sun sounded ominous: “While we can say sexual orientation shouldn’t make a difference,” wrote one columnist, “we can’t say that it won’t make a difference.”

The Canadian legal landscape has changed over these two decades, says Bill Siksay. Many gay rights issues have been resolved, including pension rights, gay people’s ability to participate in the Forces, and marriage. In 2003, Robinson pushed through a private member’s bill to extend hate-crimes protection to gays and lesbians.

“Do you know how hard it is to get through a private member’s bill?” Libby Davies says. “It’s almost impossible. It’s remarkable.”

In fact, Canada is now a world leader in terms of policy recognition for gay rights, says David Rayside, a professor of Political Science and the director of the Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies at the University of Toronto. He also points out that there has been a huge change in public opinion. Many of these changes have come in the last 20 years.

“Svend has had a role in that on the federal level, no question,” Rayside says.

Rayside and Siksay are both quick to point out that there is still ground to be covered. There is plenty of stigma surrounding those who are gay, especially in smaller towns, says Rayside. Most public school systems have made very little progress in recognizing sexual diversity among staff or students, and sexuality issues receive scant attention in the curriculum.

On the political level, Canadians have yet to elect a trans person, and many politicians are still in the closet.

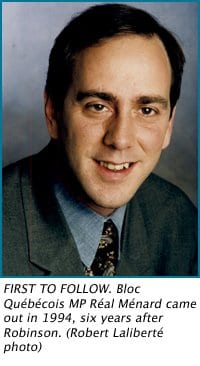

Bloc Québécois MP Réal Ménard is not one of them. He came out in 1994, and he spoke to Robinson before saying anything publicly. “Svend supported me to do my coming out,” he says. “He encouraged me.”

Still, Ménard was the first MP to follow Robinson’s lead, a full six years later. This might be an indication of how long it takes to change things in the political sphere. “I didn’t exactly start a big trend,” Robinson says. “It took years.”

“These things change gradually over time, incrementally,” says Miriam Smith, a professor at York University who studies lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender policy and politics.

She says it’s important to remember not everything has changed. “It’s still very difficult to be openly [queer] in Canadian politics,” she says. “But Svend Robinson has had a really important impact.”

Even though she is on the other side of the gender divide, Davies believes that Robinson was a role model for her and others.

Asked about the importance of this anniversary, Rayside says, “the importance is to remember folks who actually forged some of the paths. We forget that too easily. Svend was one of those people… he wasn’t perfect, but he balanced a radical perspective of what needed to be changed with an ability to work within the system.

“I think due respect ought to be given to that complex, difficult, challenging role.”

For his part, Robinson acknowledges that he could never have had an impact by himself. “I was one person,” he says. “I think it made a difference, but along with many, many other people who came out. People were open. We celebrate diversity in Canada a lot more now. And we’re a better place today because of it, I think.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra