The 519 Community Centre’s Sunday drop-in lunch is a noisy event. There’s a constant stream of people coming and going, shouting and clanking plates in the crowded second-floor lunchroom. As volunteers scurry around the musty mess hall with stacks of empty dishes piled in their arms a screen at the back of the room projects the DVD menu for a film called After The Dust, the repetition of which seems to hypnotize many of the diners.

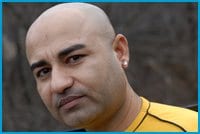

From behind the serving counter, Mahboob Ahmed smiles warmly. The 35-year-old Pakistani fled his home last June and applied for refugee status in Canada. He left behind his parents, his wife and his children, none of whom, he says, would accept his homosexuality.

“This is my family now,” he says, referring to The 519. “My family back home does not support me. I live here and I will die here in my community. So I want to do something for my community here.”

Ahmed says he fled Pakistan after a religious cleric in his hometown issued a fatwa authorizing his death. Having already been attacked by local militia group after rumours of his homosexuality spread among neighbours — and fed up with his unsympathetic father, who reacted to the news of his son’s gayness by pressuring him to marry — Ahmed fled to Toronto.

Since coming to Toronto, Ahmed has become a member of The 519 and regularly attends meetings of queer Muslim group Salaam. In a happy coincidence, he arrived in the city in the midst of last summer’s Pride celebrations and has a photo book of himself posing with various scantily clad street revellers. There’s also a series of photographs documenting his first ear piercing — something he was forbidden to do in Pakistan.

Although his refugee claim may have a good chance of being approved — a gay Muslim man from a country where homosexuality is criminalized, forcing queers into the closet and underground — refugee lawyers say Canada’s Immigration And Refugee Board (IRB) has been accepting fewer applicants than it used to.

Successful refugee applications from countries such as Iran and Pakistan have been in decline for years. Since 2000, the acceptance rate for Pakistani claimants has dropped to 41 percent from 61 percent. El-Farouk Khaki, a refugee lawyer who focusses on claims based on sexual orientation, says those numbers are symptomatic of an overall downward trend in acceptance rates.

Khaki worked for the IRB from 1989 to 1991. In 1989 Canada’s refugee acceptance rate soared at nearly 83 percent.

“There was this sense that something was wrong with our system because our success rate was higher than everybody else’s,” he says, adding successful applications varied across Canada. Last year, the overall acceptance rate was 47 percent.

In the case of queer applicants, Khaki says the board tends to be more sympathetic to claimants from countries such as Pakistan and Iran where homosexuality is illegal. (For more on homophobia in Iran check out Executable Offences.) More tenuous are the cases involving applicants from countries like Mexico. On one hand, Mexico City has a thriving queer nightlife and same-sex civil unions. On the other, groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International have rapped the Mexican government for falling short in the application of its human rights policies.

“We need to look beyond what social advances have been made to the overall human rights situation to see how rights have improved for gay people,” says Khaki. “Most Latin American countries have amazingly drafted constitutions, but that doesn’t mean it’s enforced.”

In 1989 the acceptance rate for Mexican refugees was 67 percent. By the end of 2006 it was 28 percent. The rates for acceptance of refugees claiming on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity are unclear; the IRB does not keep statistics on claimants’ reasons for seeking refugee status.

Late last year, the IRB rejected the claim of 24-year-old Mexican Leonardo Zuniga. It decided he would not face persecution if he returned to live as an openly gay man in Mexico City. But Zuniga says he fears persecution from an ex-boyfriend if he returns, in addition to the possibility of police harassment. He is appealing the decision.

IRB spokesperson Charles Hawkins says that for countries where laws and attitudes are becoming more progressive, a refugee claimant must prove they are likely to experience serious harm if they return to their country of origin. He declined to comment on specific cases or countries.

“In order for a refugee claim to be successful, the objective situation must be as such that there’s a well-founded fear of persecution,” says Hawkins.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra