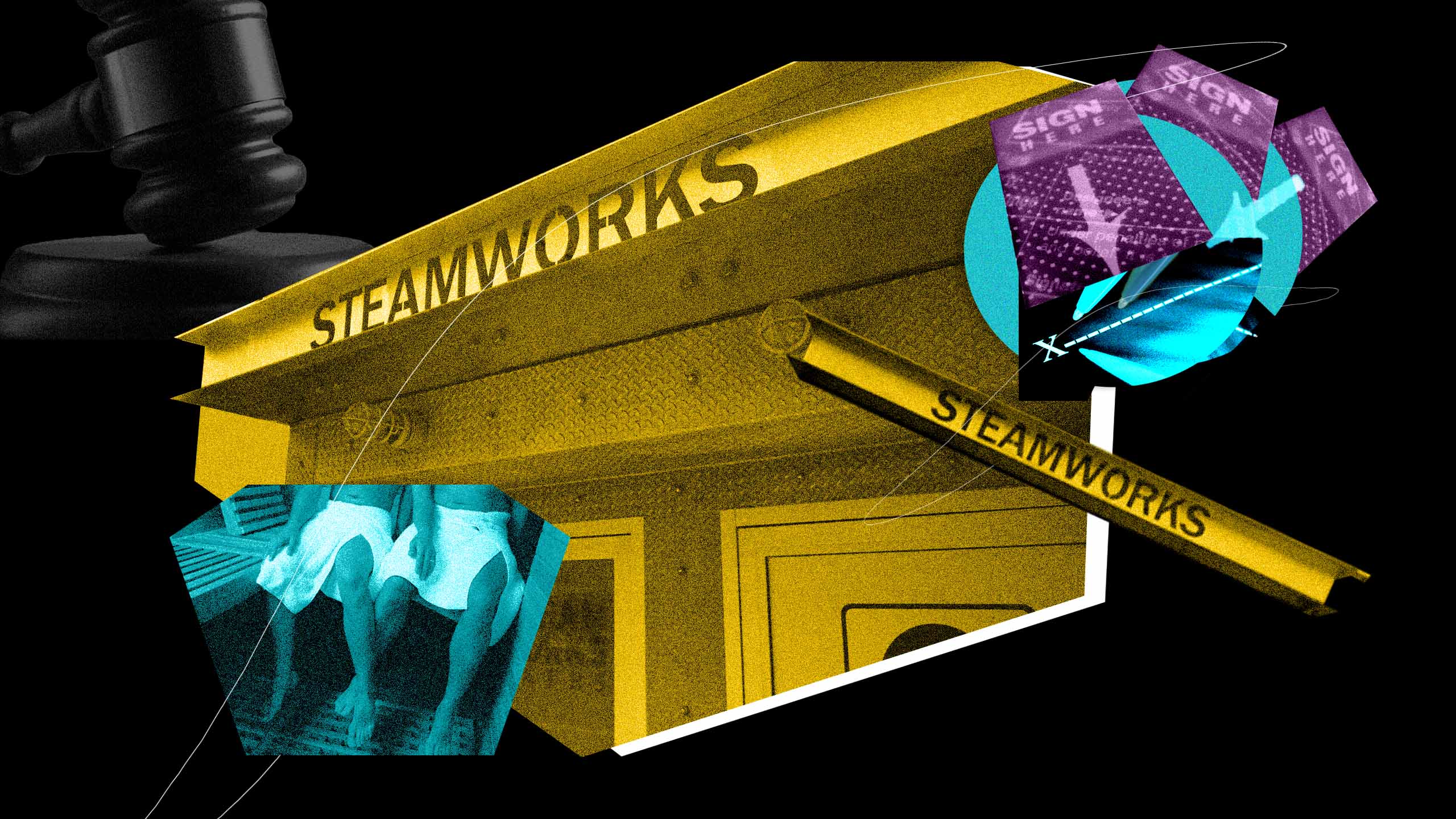

A lengthy multimillion-dollar legal battle, punctuated by allegations of attempted poisoning and using employees to deliver drugs, has been unfolding behind the scenes at one of the world’s longest-standing bathhouse chains. And the outcome remains unclear.

The fight for control of Steamworks’ five-sauna empire has been playing out in the courts since 2018 when companies controlled by business partners and former lovers Rick Stokes and Ross Moore started slinging allegations at one another via a series of complaints filed in the Superior Court of California.

The filings—which contain a series of accusations that have not been tested in court—have continued even after Stokes, Steamworks’ prominent founder, died early last year. Since Stokes’s death, two of the bathhouse locations—Toronto and Seattle—have been operated by one side of the dispute, with those in Chicago, Berkeley and Vancouver being operated by the other.

This comes at a time when Steamworks, like many bathhouses around the world, is at a turning point forced by COVID-19, mpox and a younger generation of queer men who are redefining hookups.

The man currently tasked with upgrading and reinvigorating the Toronto location told Xtra he has been worried about how various locations in the chain have been run in the years since the dispute began.

“I’m going to speak a little bit out of school here,” says Brian T. Short, who was in June named as CEO of the company that owns Toronto Steamworks. He’s also been recently appointed CEO of Steamworks Seattle. “[The other locations are] being run by people that do not visit the club, that don’t use the club, that don’t go to the club…. They’re probably not being funded properly, they’re probably not being maintained. They’re suffering.”

Alex Kiforenko, Stokes’s husband at the time of his passing, declined comment when reached by Xtra. Laurence Hickey, the manager named in the lawsuit, also declined comment, saying his lawyer advised him not to talk about the ongoing case. Moore did not respond to repeated requests for comment by press time. The managers of Steamworks in Chicago and Vancouver did not agree to be interviewed for this story.

Steamworks’ long history

Steamworks, which declares itself to be the longest continuing gay-owned bathhouse company in the world, was near and dear to Stokes’s heart, and its creation grew out of his activism in the 1960s and ’70s.

Stokes died on May 3, 2022, after a “brief battle with congestive heart failure,” states the Steamworks obituary.

Born in Oklahoma in 1935, Stokes was perhaps best known as an activist and out lawyer in California’s early gay rights (as it was then commonly referred to) movement, even organizing a “gayness booth” at a state fair.

He founded several gay organizations and, as an entrepreneur, launched his first bathhouse, San Francisco’s Ritch Street Health Club, in 1965. In 1977, he ran unsuccessfully against legendary activist Harvey Milk for a seat in San Francisco’s city government. In that election, Stokes was viewed as the suit-and-tie establishment candidate, according to The Bay Area Reporter, while Milk, who was actually five years older than Stokes, had a more confrontational, youth-oriented approach.

In 1976, the year before he ran for office, Stokes played a key role in founding Steamworks, opening what was then a single location in Berkeley, California. Over the years, as the company opened locations in Chicago, Seattle, Vancouver and Toronto, the chain became known for its cool design and high standards.

When the Toronto location opened in the heart of the city’s gay village in 2004, an estimated $2 million was spent on a nightclub-meets-factory design that was featured in the upscale monthly magazine Toronto Life. It, like the other Steamworks’ locations, had the sleek efficiency of a fast-food chain and the brand was unabashedly, cheerfully sexual. The marketing has been changing at some locations since Stokes’s death.

Steamworks was the creation of gay men of a certain generation, who came of age in the uptight 1950s, witnessed the 1969 Stonewall uprising as young people and came out of the closet with a defiant bang. If mainstream society wasn’t having them, they’d create their own communities, build their own business empires to their own tastes without apology.

The battle for control of Steamworks demonstrates that the exit strategy for this early generation of gay liberations can be equally combative.

The two companies vying for control of operations

The current dispute pits two separate companies against each other over control of the operations of the chain’s five locations: Berkeley, Chicago, Seattle, Toronto and Vancouver. Both companies have Moore and Stokes (now his estate) as shareholders, but the balance of power is different with each company.

For years, Steamworks was operated by a Berkley-based company called Great Works, a company in which Moore and Stokes equally owned a 25 percent stake. But about the time the chain expanded into Canada—first Toronto in 2004 and then Vancouver in 2007—a new management company was created.

Called Steamworks Management, LLC, it’s a separate company that was owned 50/50 by Stokes and Moore. It took over the management, operations and administrative services for the five affiliated bathhouses.

The LLC had “the goal of avoiding the direct and indirect costs otherwise demanded by third party vendors.… The LLC was not structured to nor did it generate positive net income,” states a December 2018 court filing by the LLC.

But it did control a lot of the cash flow. According to court filings by Steamworks Management, LLC, Stokes tried to diminish Moore’s role in the business—and Moore’s control of the flow of money—by having the five locations report to Great Works, a company that Stokes seemed to have greater control of.

The court battle begins

According to a series of claims filed by Steamworks Management, LLC, in the Superior Court of California since August 2018, Moore was fired by Great Works in February 2018, around the same time Stokes and Hickey transferred operations from the LLC to Great Works. This change of management was carried out, Stokes and Hickey claim in court documents, because of alleged misconduct on Moore’s part. The LLC was, at least temporarily, left as a company with no operations to manage. That situation later changed in June 2022, but at the time the LLC claimed, “Steamworks had a reasonable expectation that it would continue providing those services without interruption for years to come,” states a 2018 court filing.

The LLC claims that Great Works converted virtually all of Steamworks’ assets to its own use, including its IP, physical assets, accounts receivable and contracts with third parties, causing all of Steamworks’ employees to cease employment with the LLC and become employees of Great Works in place of Steamworks.

Because of this power grab, the LLC is claiming damages of not less than USD $1,784,000. As of the most recent court filing, Moore remains a 25 percent shareholder and a director of Great Works, but no longer holds the title of vice president.

Poisoning by window cleaner, fake emails?

After the LLC filed its August 2018 claim that the business had been taken from it without warning, Stokes, Hickey and Great Works hit back with their own claim in September 2018. They accused Moore and his then-fiancé of “grossly negligent, reckless and intentional misconduct and violations of law” that had made it “difficult or impossible” for the LLC to operate. Stokes claimed Moore’s actions during and before 2017 are what caused the clubs to terminate their contracts with the LLC.

Among the more startling claims in Stokes’s filings, Moore and his then-fiancé are accused of entering a Steamworks office after hours and spraying Windex on an employee’s trail mix “in an attempt to poison and harm him.” The filings also accuse Moore and his fiancé of removing private medical records from his office, demanding Steamworks employees purchase and deliver them “significant quantities of illegal drugs” including cocaine and methamphetamine, and “misappropriating and secreting” $100,000 of company money to an undisclosed location.

Stokes claimed the pair tried to turn staff against him by creating email accounts impersonating Stokes and Hickey and using those accounts to send insults to employees. Examples of the alleged messages include, “I was thinking of you and your disgusting body,” and “I look forward to the day you have to move back in with you [sic] homophobic parents.”

Court documents claim Moore and his fiancé also made verbal statements suggesting they were “waiting for Rick to die” so they could take control of the business.

Stokes sued for damages in an amount to be determined at trial, claiming Moore had a vendetta against him since Moore was fired from Great Works in 2018. Documents filed since Stokes’s death last year say his estate or successors “will be needed to substitute as defendants in place of him” in the case. Claims that were personal to Stokes—the alleged invasion of privacy and false impersonation—do not pass on to the estate or heirs, so they most likely will be dismissed if and when the case comes to court.

In April 2019, all parties agreed to stay proceedings and work on a resolution through mediation. But a follow-up meeting to determine next steps has been repeatedly delayed and is now scheduled for April 26, 2023.

The effects on operations

On the ground, managers at two Steamworks locations told Xtra they have not been aware of the drama unfolding behind closed doors and in the courthouse.

“I’m happy and it’s lovely and it’s wonderful and busy here,” says Zose Newell, who has been general manager of the Berkeley location for five years.

Newell says Moore and Stokes would both visit the bathhouse on occasion and their interactions were always pleasant.

“Both very friendly, charming rich men. They were lovely to work for and a pleasure. I never had any issues with either,” he says. “I think everyone would say that across the board, pretty much.”

Joe Wilkins, general manager of Steamworks Toronto, started working at the club in December 2018 and was promoted to GM last year. He said he was not privy to any details about disputes between the owners, but says management changes following Stokes’s death “led to an internal upheaval that restructured how the clubs are run.”

Since Stokes’s death last May, Moore and his team have obtained control of the bathhouses in Toronto and Seattle. In June 2022, Moore moved to take sole directorship of the Toronto Steamworks location, which is owned by a numbered company registered in Nova Scotia. That meant removing Hickey from his CFO role there, according to an ownership document obtained by Xtra. Moore was named as director, officer and vice president, while Short, the man who supervised the original design of Steamworks Toronto, was named officer and CEO. Moore and Short also took over these roles at the Seattle location, Short told Xtra.

Short says Moore has also an equal owner partnership in the Berkeley, Chicago and Vancouver locations, “he just doesn’t have a management say in the other ones, unfortunately.”

Signs of the dispute have made their way into how the chain is run, with Toronto and Seattle locations setting off in different directions than the others. In the last year, the Steamworks website has split, with the Moore-run Toronto and Seattle locations at one URL, the Chicago, Berkeley and Vancouver locations hosted on another. The logos and graphic design at all the locations remain the same or similar.

As CEO and the original project manager when Steamworks Toronto opened, Short has plans to give the place a facelift. He says he’s fixing lighting and sound issues to reclaim the original feel and mood of the club, saying it was neglected in recent years. He also has opinions of the clubs that aren’t controlled by him and Moore.

“So many things had just gotten so far out of hand, in my estimation, from where they were when we set the place up,” Short says. “They went through a period of neglect and mismanagement and that has changed now with Ross taking back control of the clubs.”

Read part two of our focus on the business of bathhouses, with a look at how the industry is trying to stay relevant for a new generation of men who have sex with men.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra