Dress it as we may, feather it, daub it with gold, huzza it, and sing swaggering songs about it, what is war, nine times out of ten, but murder in uniform? —Douglas Jerrold

Welcome to Trench Life: A Survival Guide, a new exhibit at the Canadian War Museum.

It sheds light on the culture of the trenches of the First World War. The exhibit promises photos, letters, music, graffiti and newspapers. But it’s the cross-dressing soldiers that are most intriguing.

Canada — population 8 million — saw 600,000 young men enlisted in the First World War. There is no record of how many were gay soldiers. Historian Tim Cook is reluctant to speculate.

It’s a slow process going through the exhibit; there’s simply so much to see. Letters to home speak of friends, food and weather with references to live action often blacked out by censors. The letters surround large, aged black-and-white photos of soldiers, grim-faced and tired in the trenches, or smiling as they lounge against a wall in the back barricades.

There’s also a section for the newspapers they created together and all the while, rousing hymns — the music sung to buoy spirits — marks each step through.

Cook gestures to a photograph of young men grinning as they read through one of their self-published newspapers.

“60,000 Canadians died,” he says. “But while they were there, they had to bring some normalcy in their lives. It was a necessity. It was a way to cope.”

Cook mulls over questions on homosexuality in the army. It’s clearly not a question he gets often.

“Homosexual conduct was illegal and men were charged for it; we don’t know how many. There are 15,000 court marshal records. But because it would often be called something different, like ‘conduct unbecoming,’ it’s complicated. No one has gone through to learn how many gay soldiers were charged. It would be a completely hit and miss process.”

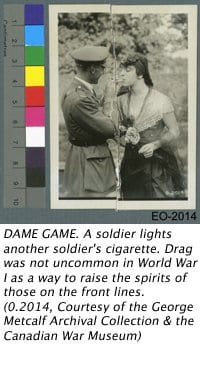

Cook gestures to a large photograph featuring a line-up of soldiers in drag.

“On top of that people didn’t talk about sex then. Even between heterosexual couples, in letters there’s seldom any reference to sex. So while being homosexual was illegal and never talked about, at the same time, it was normal and expected to have cross-dressing. There were these plays and cabarets and because there were no women to play the female parts, it was expected that men would. These cross-dressing acts were wildly popular.”

As we look closely at the thick make-up, pert dresses and coy smiles, Cook adds, “It’s been suggested there was a homoerotism to these girls. It wasn’t at all unusual for men to fall in love with one of the girls performing.”

It’s a challenge to reconcile the flirtatious whimsy of the doe-eyed drag in the photograph with the darkness and drudgery of war. While gay sex would land men in prison, one could dress up and indulge in the fantasy for a few moments, but only under a social guise.

If there is supposed to be reassurance in this, for this writer, it’s that in a nightmarish space, there were snippets of laughter, fantasy, cross-dressing and friendship. Small mercies indeed.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra