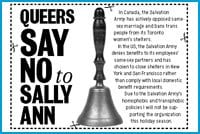

You know that Christmas is in the air when the Salvation Army bell-ringers pop-up on street corners collecting donations for the needy. Many people will toss a few bucks in the plastic ball without much thought. But folks of the queer persuasion should think twice before donating, considering the organization’s polices toward homosexuality.

In previous years, I’ve passed the bell-ringer at Wellesley subway with a sense of mild irritation. But this year, I’m surprised to find one at the corner of Church and Wellesley, in the heart of the gay village.

The Sally Ann, as it’s often referred to, is a branch of the Evangelical Christian Church that aims to help people in need through a broad system of social programs. While that’s all well and good, they’re also strong opponents of same-sex marriage, as well as any expression of sexuality outside of traditional heterosexual marriage. I’m curious why they feel it’s appropriate to come asking queers for money given their policies, so I decide to chat up the bell-ringer to see if he can shed any light on the situation.

I can feel myself bristling as I approach him, getting ready for a fight, but when I start asking him questions, he barely replies, muttering under his breath and staring at the ground.

Later, I end up talking with a local coffee-shop employee who tells me the bell-ringer has been under siege all day, with passersby hurling abuse and partially consumed lattes in his direction. No wonder he didn’t want to talk to me.

Having failed to get a satisfactory explanation from the bashful bell-ringer, I decide to ring up the Salvation Army’s regional office for some clarification. I’m patched through to Ken Percy, PR director for the GTA. Percy is quick to tell me that his organization does not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation — before I’ve even asked about it.

I can’t help but feel this is a statement made because he knows he’s talking to a queer paper. “We don’t necessarily agree with everyone’s lifestyle or choices, but we will not discriminate against them,” says Percy.

The Salvation Army’s websites offers much the same, along with a carefully worded position statement on homosexuality that’s essentially a jazzed up version of the standard “love the sinner, hate the sin” doctrine. Percy points out that the Salvation Army has been offering domestic partner benefits for same-sex employees in Ontario since 1999 when the Ontario Human Rights Code was amended to require it or, in his own words, “as long as we’ve been allowed to.” Um, do you mean as long as you’ve been forced?

Things are a bit different in the US, however, where there no comparable laws exist at a national level. In 1998 when San Francisco passed legislation requiring organizations receiving funding from the city to provide benefits for same-sex employees, the Salvation Army gave up its contract with the city to provide services such as homeless shelters, rather than comply. A similar situation took place in New York in 2004.

The Salvation Army remains opposed to same-sex marriage and, according to the Evangelical Fellowship Of Canada (EFC), posted an EFC form letter to one of its websites for concerned citizens to use in lobbying their MPs to vote against same-sex marriage legislation.

When I ask if they’ve ever donated funds to fight same-sex marriage, Percy refers me to Andrew Burditt, the PR director for the Salvation Army’s national office. According to Burditt, the Army has never used any government funding to fight marriage equality. As for money collected through donations, Burditt tells me that he “wouldn’t be able to speak to what any individual churches have done.”

“We follow biblical principles,” he adds. “We are a Christian church and we do not seek to hide that.”

When asked why queers should donate to the Salvation Army given their policies, Percy stresses that the organization helps 1.5 million people a year and that they don’t discriminate in providing services. That’s if you ignore the fact that transsexuals were banned from the Salvation Army’s Toronto women’s shelters in 2001.

Percy also tells me the bell-ringer from Church St is gay and that he had come to them suggesting that that corner would be a good place to raise funds. I start to feel bad for bell-ringer, and decide that even though I’m not sold on donating to his cause I’ll bring him a coffee the next day.

When I arrive at the corner the following afternoon the bell-ringer is nowhere to be seen. Turns out that some of the local business owners, fed up with complaints, asked him not to come back. I decide instead to give the two bucks I was going to spend on the coffee to a homeless woman panning for change outside the subway. Now that’s what Christmas should be about.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra