The revolution starts with a slow dance.

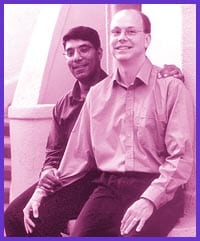

Doug Arcand and Alnoor Karmali were sitting quietly at their table at the Scotiabank 1998 Christmas party, surrounded by 500 of Arcand’s colleagues.

“By the time Alnoor and I went to my office party, I was already out and they already expected me to take a guy,” says Arcand. “We’d made a big decision that we were going to [slow dance] – and it was nerve-wracking, heart pounding leading up to it, the whole bit.

“Reactions? Not directly. There was silence.”

When the two made the same foray at the Ralston Purina office party, it was a bigger step for Karmali, who had never even been to the party before.

“I decided I had to come out at my workplace,” says Karmali, “and I had been there four years.

“So we went. I was very nervous, my hands were all sweaty as we sat down. Then of course sitting next to me is my boss, so I had to introduce Doug to my boss.

“We started listening to the music, waiting for a slow dance. It took forever. Eventually they played one and we got up and danced. We had to go in a circle and I was holding him and I could see people – I saw this one woman and she had her mouth open.

“I went back to work the following Monday and I didn’t hear anything. I didn’t notice anything, people were very pleasant to me. So I asked my boss, ‘Is no one saying anything?’

“She said, ‘You know, my phone is melting!'”

Shocking the bank and dog food crowd is all in a day’s work for the two men, two of the sweetest everyday revolutionaries around.

Born and raised in Hamilton, Arcand was 26 before he was comfortable enough with his sexuality to start volunteering with Hamilton United Gay Societies (HUGS). Now 41, he came out the same day as did New Democrat Svend Robinson – when the federal politician’s sexuality made news, HUGS needed someone to talk to the press, and Arcand decided it was time.

“I told my parents I was going to do this. I explained to them how important it was that gay people had a face and a name. I didn’t get their blessing, but they did say, ‘Do what you think is right.’ So I did.”

Born in Uganda, Karmali’s family was exiled from the African country and chose first England, then Canada as their home. Raised a Muslim, Karmali’s sexuality has been a personal struggle for him to reconcile with his faith.

“It’s very hard for me to see where being gay fits in with being Muslim,” says Karmali, 32, who hasn’t been to mosque in a couple of years. “To me, it doesn’t fit. To me it was a choice – ‘Alnoor, are you a Muslim or are you gay?’ Well, I’m gay. You can’t hide.”

Karmali says that although his parents would like him to attend mosque, they understand. They are a close family, and accepting of Arcand, despite the couple’s cultural differences.

Arcand says he’s learned a lot about family from his lover – while Arcand’s relationship with his parents continues to improve, his sister hasn’t spoken with him for almost 10 years, keeping him from seeing his two young nieces.

“It broke my heart, it really does, ’cause they’re great kids,” says Arcand. “Isn’t it better to teach them about sex and that love is great than teaching them hatred?”

The two met at an Out And Out men’s weekend in 1995, and have been together ever since. Arcand works as a computer programmer, and does the website for the Coalition For Lesbian And Gay Rights In Ontario (at www.web.net/~clgro/); Karmali works in mutual funds and volunteers with Out And Out. They live a quiet life on a quiet street in downtown Toronto – quietly changing the world.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra