Every school-child has heard of Alexander The Great, the famous king who was born in Pella, Macedon in the summer of 356 BCE and died 33 years later in Babylon, having conquered almost every part of the world he knew. His powerful and ruthless father, Phillip Of Macedon, had taken control of Classical Greece and longed to challenge Persia, the greatest empire of the time. Phillip was famed for his amorous attachments to men and women. Alexander’s mother Olympias was an enigmatic and equally ruthless princess from Epirus, in modern day Albania. Alexander believed that his ancestry went back to Heracles on his father’s side, and Achilles on his mother’s.

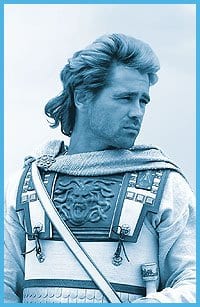

Mere months after the classical legends of Achilles and Patroclos were brought to the big screen in Troy, the spirit of Alexander The Great is about to visit the world again, thanks to an Oliver Stone epic opening Wed, Nov 24.

In Troy, the relationship of Brad Pitt’s Achilles and his cousin Patroclos was utterly unerotic, despite the general assumption in ancient Greece that they were lovers. Alexander also had his share of speculation on the nature of his relationships with the men in his life, both during his lifetime and long after his death. Though Stone is claiming that the film will take on Alexander’s “bisexuality,” it’s hard not to be skeptical, especially after rumours that the release date was delayed to tone down the man-on-man action.

The past is a foreign country. Human nature may not change, but customs and attitudes do. People express love and sexuality in ways that are available, permitted or encouraged in their own lifetime. Though men will always fall in love with men and women with women, it’s unwise to project modern concepts of what it is to be lesbian or gay onto the ancient world. But it’s just as foolish to paint Alexander or Achilles as strictly heterosexual.

For Alexander, same-sex relationships with young men who were his equals would have been normal and expected. As a prince, he was provided with syntrophoi – foster brothers – from noble families. They served the prince, hunted with him and protected him while he slept. Seven of them, the somatophylakes, were intimate companions who dined with him and had the right to speak freely. Alexander was absolutely loyal to these friends for the rest of his life.

As a young man, Alexanderis reported to have been very restrained in his sexuality, almost to the point of indifference. The historian Athenaeus (c 200 CE) says that “Alexander had little appetite for sexual activity. Olympias (and Phillip)… had the Thessalian courtesan Callixena, who was very beautiful, go to bed with him… for they wanted to make sure that he was not effeminate. Olympias often begged him to have sex with Callixena.”

According to Plutarch (46-119 CE), Alexander “would state that his awareness of his mortality arose most from sleeping and the sexual act, as if to say that tiredness and pleasure derived from the same weakness in nature.”

Alexander’s warmest and most lasting relationships were with men. Whether sexual or not, his relationship with one of his companions, the tall, beautiful Hephaestion, continued through their adult years is something that can’t be known, but they remained companions on and off the battlefield as long as they both lived. All ancient authors agree that Alexander loved Hephaestion “more than all the world.”

With remarkable intimacy, they would even sit together and read from the same text. Plutarch tells that once when Alexander was reading a letter from his imperious mother, “he took off his ring and put the seal to Hephaestion’s lips” trusting his friend to keep any secrets. Even more suggestive of the nature of their relationship was their behaviour when they went to Troy. Alexander placed a wreath (some sources say he dedicated a suit of armour) on the tomb of Achilles while Hephaestion did the same at the tomb of Patroclos, explicitly comparing themselves to the legendary lovers.

Another incident shows that Alexander counted their love above kingly pride or even vanity. Valerius Maximus writing around 20 CE, tells a story of an event during the Persian war. After taking possession of Darius’ camp, which contained all the king’s relatives, Alexander came to address these latter, with his dear friend Hephaestion at his side. Darius’ mother, encouraged by his visit, lifted her head from the ground where she had prostrated herself, and in the Persian fashion did obeisance to Hephaestion and saluted him as Alexander, since he was the superior of the two in height and good looks. Apprised of her mistake, she became extremely agitated and was searching for words of apology when Alexander said to her, “Your confusion over the name is unimportant, for this man is also Alexander.”

At age 27, Alexander married so he could have an heir to his vast kingdom. Whatever Alexander’s sexual preferences, he eventually married several wives. He chose women of exceptional beauty and expected these marriages to produce offspring. Though he inherited an enormous harem from the Persian king, he fathered only two children. A son, Heracles, was born to a captive woman named Barsine; his wife Roxanna was pregnant with his son when Alexander died.

He was susceptible to beauty. Though he railed against a governor who offered to sell him two exceedingly good-looking boys, asking what “moral failure” the man had seen in him to make such an offer, he later fell in love with a young Persian, the eunuch Bagoas. Bagoas was a dancer of exceptional intelligence and loyalty as well as great beauty. On one occasion, during a festival, Bagoas won a prize for his dancing. He came through the theatre in his finery and sat down beside the king. The Macedonian soldiers in the audience clapped and shouted for Alexander to kiss him. Alexander took Bagoas in his arms and kissed him in front of everyone.

But it was Hephaestion whose love sustained and comforted the conqueror. Together, Alexander and Hephaestion fought their way across Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan to the gates of India. At Ecbatana in Persia, in 324 BCE, Alexander was celebrating his victories with days of athletic competitions and nights of hard drinking. Hephaestion fell ill and died. Alexander nearly went mad with grief. Arrian, writing around 140 CE, says he “completely succumbed to rage, passion and tears.” He flung himself on the body, spending all day and night weeping. He refused to leave his friend until the other companions came and carried him away. He cut off his hair, as Achilles had done over the corpse of Patroclos. No one was appointed to fill Hephaestion’s empty place among the companions.

The funeral was one of the grandest in all history. Alexander spent more than a king’s ransom, more than ten thousand talents of gold, and some sources say he actually drove the hearse himself. Just as Achilles had held funeral games for Patroclos, Alexander held games and contests in literature and music. Three thousand athletes and artists took part. Alexander gradually took up his normal life again, but died before a year was out.

How will Oliver Stone’s film treat all this? The last major film version of the story, with a young Richard Burton wearing what appeared to be a wig borrowed from Mae West, made much of Barsine, very little of Hephaestion and ignored Bagoas entirely. The historical Alexander also had a wonderfully butch half-sister, Cynnane who refused to marry again after the death of the husband she’d been given to as a girl. She trained as a soldier and became a general. There are a lot of interesting queer tales from the Ancient World. Will Holly-wood tell any of them?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra