They’re up-and-coming neighbourhoods: rough and tumble and edgy but with a certain amount of charm. Gradually, they become known as hip, affordable alternatives to suburban living; as that happens, people buy property and renovate.

This often puts new residents at odds with the frequently scruffier set that pre-dates their arrival.

Gentrification comes hand in hand with new residents wanting to redefine the character of the neighbourhood. Often, community associations are formed and protecting property values becomes a priority. Original residents who do not represent the ideal of the suitable neighbour are forced out, usually under the guise of safety concerns.

Gays have a long history with gentrification, first as its victims and then as its ostensible agents. Most famously, a bustling queer underground was squeezed out of downtown Montreal’s Peel St neighbourhood in the 1970s (we regrouped further down Ste Catherine St in what is now the gay village).

To feel safe is an innocuous request — everyone wants to feel safe — but for some associations, it’s a wedge used in two ways. Firstly, neighbourhood associations pressure police to step up their presence in the area. Then, when they find the existing laws — or the police’s interest in enforcing them — lacking, they lobby municipal and provincial politicians to introduce new laws to make evictions and criminal prosecutions easier.

And that makes them — with their law-and-order agenda — an essentially conservative movement. Over the past 20 years, these associations have become increasingly savvy at fighting for their cause and influential in dictating city and provincial legislation.

Case in point: in the 1980s, during a bout of gentrification, the Lowertown Community Association used economic and political capital to lobby for more police. It worked, and gradually police pushed undesirables — the homeless, drug users and street-level sex workers — out of Lowertown and into Hintonburg and Vanier.

Then the gentrification of Hintonburg began. Cheryl Parrott is a member of the security committee of the Hintonburg Community Association and a woman dedicated to improving her neighbourhood. Parrott has been part of the association since it formed in 1991 — she is one of the founding members — and through her efforts, the security committee worked with city councillors and police to reduce crime in Hintonburg and across the city of Ottawa.

“Part of the process we have gone through is finding out what laws we have and where the gaps are,” says Parrott. “Then trying to figure out how you fill that in. At what level of government and what committee, and is it provincial or is it federal?”

Parrott and the security committee have been successful at jostling politicians to take up their ideas and have been forthright in their courtship of Ottawa’s politicos.

“When politicians were running for the provincial legislature in the last election,” says Parrott, “we took them all on a walkabout and talked to them about the issues in the community and about SCAN [Safer Communities and Neighbourhoods] legislation. By then, we felt it was something that really would be another tool facing the habitual problem properties.”

Their walkabout was a success, and Yasir Naqvi, who was later elected MPP for Ottawa Centre, took up Parrott’s cause as his own.

“We’ll certainly be working very hard to make sure it gets back into the legislature and has a chance for third reading,” says Parrott.

Professor Christine Bruckert, from the department of criminology at the University of Ottawa, is not a fan of neighbourhood associations. She refers to them as a middle class movement not interested in the rights of ordinary people — in short, they are not a populist movement.

“They are supposed to be community organizations — community based on a spatial definition,” says Bruckert. “There are people living together in close proximity, and yet they are explicitly exclusionary.”

In some cases, the community associations have little to do with the neighbourhoods they purport to represent. In at least one case, the group’s meetings aren’t even public.

Meanwhile, a case study of the Hintonburg Community Association shows their power on the ascendant. Together for Vanier (that neighbourhood’s association), now just three years old, is already finding its feet.

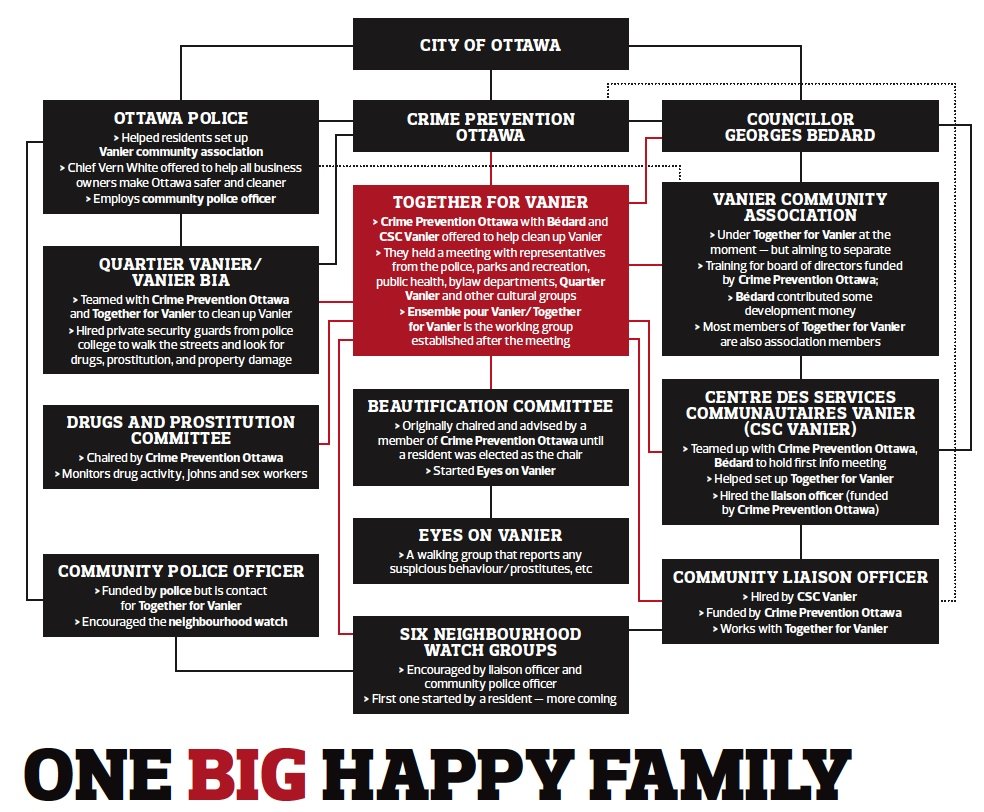

Bruckert’s position is borne out by research conducted by Xtra that shows a steady flow of help from the City of Ottawa and the Ottawa Police Service to neighbourhood associations — which in turn lobby for more invasive police measures. Rather than grassroots organizations, our research shows a well-connected network that meets, shares members and lobbies together.

CASE STUDY >> Tight nest includes city, police and community associations

Together for Vanier is peculiar among neighbourhood associations in that it wasn’t started by a groundswell of community support.

It was started (and funded) by the city-run Crime Prevention Ottawa (CPO) and has links to the area’s business association, city councillor and other neighbourhood associations.

In 2007, CPO — itself closely tied to Ottawa Police Services — started Together for Vanier as part of their community development initiative to combat crime. The working group was formed after CPO held an information meeting with Vanier community leaders, police and councillor Georges Bédard.

CPO is still actively guiding Together for Vanier three years later.

CPO funds the group’s community liaison position and a CPO staffer chairs the group’s drugs and prostitution committee. With the success of Together for Vanier, residents started a separate neighbourhood association called the Vanier Community Association.

CPO funded the training of its board of directors, and Councillor Bédard also contributed money to the development of the association. For now, the association works under the umbrella of CPO and Together for Vanier.

Together for Vanier’s members are mainly from north of Montreal Rd, an area that is being slowly gentrified. Many members belong to both Together for Vanier and the residents’ association.

None of which is, in itself, sinister. But as both city council and the police begin to use neighbourhood groups as political cover, it is worth noting that influence flows in both directions. And this complex nest of connections contradicts the perception that Together for Vanier is a grassroots group and represents the neighbourhood.

Together for Vanier has done some good work. Its beautification committee has taken a lead in cleaning up the parks, reclaiming concrete flower boxes once filled with garbage, starting an adopt-a-garbage-can program and establishing community gardens.

But Together for Vanier is also vigilant. Members of the Eyes on Vanier walking club meet to walk their dogs — armed with cell phones to report any suspicious activity.

The drugs and prostitution committee publishes tips on its website for spotting and reporting suspected sex workers and johns.

With the encouragement of the police, a neigbourhood watch was started — there are now six active watches in the area. Even Vanier’s business association, Quartier Vanier, has stepped in, hiring private security officers to walk commercial avenues.

Together for Vanier is not yet as politically powerful as the Hintonburg Community Association — they have not driven any legislative actions and remain undecided on SCAN. But as they become more established, how will they use their clout?

POWER PLAY

In 2008, several of these groups — neighbourhood associations, police and Crime Prevention Ottawa — came together to applaud Liberal MPP Yasir Naqvi for introducing a private member’s bill that would make it easier to evict bad tenants. Naqvi made the announcement at the Hintonburg Community Centre.

Police officers stand behind Cheryl Parrott of the Hintonburg Community Association (left) and a member of Crime Prevention Ottawa.

Crime Prevention Ottawa head Nancy Worsfold listens behind Vanier councillor Georges Bédard. Both endorsed Naqvi’s bill, which was introduced at the prompting of the Hintonburg Community Association.

Ottawa police chief Vern White spoke in favour of the bill. He brought more than a half dozen patrolmen with him to the press conference.

Housing Helps and Prostitutes of Ottawa-Gatineau Work, Educate, Resist (POWER) crashed the party. Former AIDS Committee of Ottawa staffer Nicholas Little was among those who protested the announcement.

University of Ottawa professor Christine Bruckert followed a heated discussion between Little and Naqvi.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra