Credit: Flickr

I scoured Israel and Germany in 1998 to find Second World War gay underground resistance hero Gad Beck. When I found him, Beck gave me one of the most memorable interviews I’ve ever done. The last known gay Jewish survivor of the Holocaust, Beck died June 24 in a retirement home in Berlin, just six days short of his 89th birthday. He is survived by Julius Laufer, his partner of 35 years. Here is my December 1998 interview with Gad Beck.

Gad Beck remembers falling in love with Manfred Lewin, another Jewish gay teenager who lived in a poor Berlin neighbourhood in Nazi Germany.

Hitler had been crowned chancellor nine years earlier, in 1933, when Beck was just 10 years old. By the time Beck realized he was attracted to men, though, Germany’s burgeoning gay movement, embraced by the pre-Nazi Weimar Republic, had been all but crushed. More than 100 gay bars and political organizations had been wiped out in Berlin, and Himmler himself later boasted the Nazis had killed a million gay men between 1938 and 1944.

“When I was 17 or 18, there weren’t a lot of gay bars for Jewish gays,” Gad said. “This was the problem – I had no place [to go]. So I was a bit lonely.”

Until he met Lewin. But it was October 1942 and the Nazis were transporting Jews east. When the Gestapo rounded up Lewin’s family, Beck borrowed a neighbour’s Hitler Youth uniform and marched into the transit camp in a bid to free his first love.

Beck, classified as a half-Jew or “half-breed” by the authorities (his father was Jewish, but his mother had converted to Judaism), convinced an officer to temporarily put Lewin into his custody. Once outside the camp, though, Lewin stopped dead in his tracks.

“I was going out with him from the ‘locker’ and I said, ‘Manfred, now you are free – come!’ And he said no,” Gad explained. “And it’s important to understand this: Manfred said, ‘I will never be free if I am not near my family. They are old and they are ill and I have to help them.’ And he went back to the locker without saying goodbye to me. I never saw him again. His entire family died in Auschwitz.

“It was then I decided to help my friends before they [too] were put on the list,” Beck told me.

Within a year he was the leader of Chug Chaluzi – the Pioneer Group – which helped feed, shelter and transport more than 100 Jews as part of the Europe-wide Zionist resistance movement Hechalutz, the Pioneers.

Beck’s Pioneer group included his twin sister, Miriam (aka Margot). “We had very good help from the Pioneers in Switzerland,” Beck said. “I got from their Swiss attaché money and information – I learned what was happening and what would happen.”

While Beck stated unequivocally that his sexuality didn’t motivate him to fight the Nazis – “for them I was Jewish” – it did influence the way he fought back.

“If you are a member of a minority there is a place where you can find yourself. Every night I thought, ‘Tomorrow I will be sent to the camps.’ But every night I was not alone. Love was the only thing that gave me strength to fight Hitler and his politics. I had the love and loyalty of my friends. Love gave us the force to fight.”

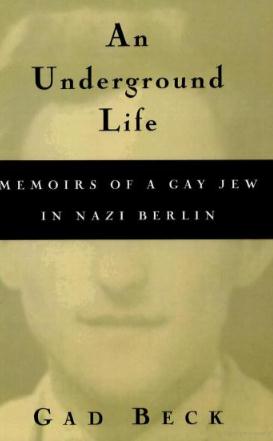

Beck, whose translated memoir, Gad has Gone to David, was published in America in 1999 as An Underground Life: Memoirs of a Gay Jew in Nazi Berlin, felt a similar solidarity within the gay civil rights movement. “I feel I have to fight for more liberty for gays. Even today we are not liberated. We are just beginning.”

Beck was a keynote speaker when the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum dedicated its gay and lesbian fund in 1996 and the following year rode in New York City’s Pride parade. “It was the first time and it was the last. It was very nice and they made me feel like a hero – ‘You are our hero!’” Beck explained, but then told me, “Dah-ling, it is not serious! I am not a hero.”

He scolded me when I insisted he was. “Look, if I am a hero, I am a little one. Everyone has to fight sometime in their life.”

After the war Beck helped transport Jews to Palestine, fought in Israel’s war for independence and worked as a psychologist in Tel Aviv for 12 years. But in 1978 he returned to Berlin to become director of the Jewish Adult Education Centre. His sister Miriam (Margot) remained in Israel with her five children. “She is very happy and very fat!”

It was only after returning to Europe, though, that Beck met his second “husband,” Julius Laufer (15 years his junior), in Vienna.

“I met this beautiful young man in a coffeehouse, and he could only speak Czech,” Beck said. “It turns out his father was my comrade in the underground, fighting for me and my group in Prague [during the war]. One day, the Gestapo took his father to prison and he ended up in a concentration camp in Austria. And now here was his son.” Beck’s voice swelled with emotion. “I will never leave this man. He is my great love.”

Beck met his first husband, Zwi Abrahamssohn, decades earlier when he was captured during the last days of the war. A Jewish girl betrayed them. “More than six SS officers took me and Zwi and put us into a basement cell [in the Jewish Hospital] in Berlin from February 1945 to April 1945.”

It was here that Beck, feverish and wounded when the Allies bombed the city, convinced the Gestapo chief not to kill 1,000 Jews to celebrate Hitler’s birthday on April 20. Meanwhile, the battle of Berlin raged on in the streets above. “I told the Gestapo chief, ‘The Russians are one kilometre away – I will be the winner, not you,’” Beck recalled. He told the chief Russian mercy could be negotiated if the Gestapo spared the 1,000 lives.

It worked.

“I was liberated by a Jewish soldier of the Russian Army, and he asked me in Yiddish, ‘Are you Gad Beck?’ I said I was. He was so beautiful I could have fallen in love with him. ‘Brother,’ he told me, ‘now you are free.’ And he kissed me.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra