Buller man. Batty bwoy. Vile names, vile words, indeed. And yet, Wesley Crichlow, author of Buller Men And Batty Bwoys: Hidden Men In Toronto And Halifax Black Communities, wants to reclaim those words and make them proper and correct adjectives for grounding the differences between black gay men and white gay men. Crichlow’s task is a difficult one – and he’s not entirely successful – but he has a wealth of rich interviews from 19 men with which to work.

Crichlow’s reclaiming of buller man and batty bwoy is deeply indebted to Audre Lorde’s Zami: A New Spelling Of My Name. Lorde attempted to reclaim zami as an epistemologically respectable name for women of the African diaspora who have sex with women. Zami signaled a range of social relations among women that included sex, but not exclusively. Equally important to Lorde’s Zami is its “biomytho- graphy.” Zami is not a straight auto-biography in any imaginable way; jumbling together myth and reality is an important part of Lorde’s truly subversive, genre-breaking text. Unlike most autobiographies, Lorde’s is not a realist narrative in its entirety.

Buller Men And Batty Bwoys is a socially real narrative that vividly reproduces the experiences of some black men who have sex with men. Crichlow offers a partial autobiography that places his experience within the context of the issues of family, community, violence, pleasure and love. An intriguing section tackles Crichlow’s involvement with black nationalist organizations like the Biko-Rodney Malcolm Coalition and the Azania Movement, where he felt that expressing his gay self could not be fully realized nor, more importantly, affirmed.

The most successful sections of the book are the interviews, for they offer a wide range of insights into how some black men negotiate their relationship to various aspects of black nationalism. Some of the men refuse it altogether; others remain silent about their sexuality; others attempt to place sexuality on the agenda; and yet others operate with skill and nuance between silence and resistance. The stories the men share are instructive and moving.

Buller Men And Batty Bwoys details stories of pleasure, pain, violence and racism. For me the most poignant come from the older men in the study. One speaks about the complex relations of coming out late in life, after having a family. “Well, just before I left my family I started to become addicted to alcohol and non-prescribed drugs,” he states. “I am also 65 and live a very lonely life. The apartment building which I live in has a seniors club, and I try to keep myself occupied with the club as much as possible.”

Older black men and men of colour might be the most disadvantaged, still invisible in these days of gay visibility.

However, I don’t think all is really lost. The late Essex Hemphill once retold an encounter he had with a young black child in Washington, DC when he wore a T-shirt with the words “Fag Club” emblazoned on it. The child announced in a store “Look, everybody, there’s a faggot in the store!” Hemphill then tells us, the child approached him and asked where he got his T-shirt. The child thought that his cousin would like one of the shirts, since his cousin was a faggot, too. When Hemphill tells the child he got the T-shirt in San Francisco and not DC, the child replies: “I didn’t think you could get a T-shirt like that in DC.” Hemphill’s story is one about the ambivalence of language and all the ways in which the profanity of language can be re-appropriated and remade to signal, confirm and affirm difference.

Language, words, names are political. Crichlow’s book announces a need for such a conversation containing as it does all the political differences in the Canadian context for black men who have sex with men. While I was particularly taken with the interviewees’ stories, I found the book’s analytical framework disappointing.

So, after reading Buller Men And Batty Bwoys, one is still left wondering: “What’s a black faggot to do?”

* Rinaldo Walcott is Canada research chair of Social Justice And Cultural Studies at OISE; Insomniac Press recently released a revised edition of his book Black Like Who: Writing Black Canada.

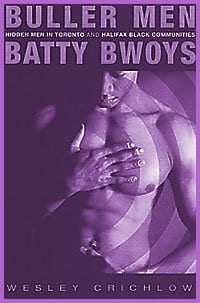

BULLER MEN AND BATTY BWOYS: HIDDEN MEN IN TORONTO AND HALIFAX BLACK COMMUNITIES.

Wesley Crichlow.

University Of Toronto Press.

256 pages. $45.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra