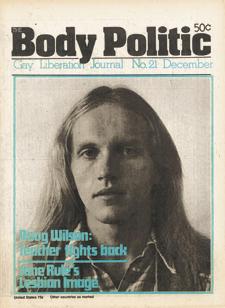

FLARE. In the documentary Stubblejumper, actor Jesse Owen plays Douglas Wilson, a prairie boy who rose to national prominence in the 1970s as a gay rights and social activist. Credit: Photo: Gerald Hannon

Early gay activists were, by and large, a homely crowd (or was it just that the 1970s, sartorially and otherwise, were not kind to anybody?). The troll-ish, among whom I count myself, are still mostly with us. The beauties often died young. Doug Wilson, the subject of Stubblejumper, Regina-native David Geiss’s new film, was one of them. Wilson died in 1992 of AIDS at the age of 42 — not young, exactly, but young-ish, the angelic good looks of his youth transformed by then into a settled and appealing maturity.

Outside of an aging group of activists, few remember Wilson. He is one of the many early rights pioneers who are largely unknown to the subsequent generations who have profited from their daring. Geiss, who is 26, had never heard of him, though he’s a devoted Saskatchistani (he says he hopes to “get a piece of land and retire here one day”), and Wilson was a Saskatchewan farm boy who burst onto the news pages when he was a 25-year-old education student at the University of Saskatchewan in Saskatoon. Wilson placed an ad in the campus newspaper, hoping to awaken interest in starting a gay academic union. He used his real name. This was 1975, and the administration freaked — Wilson’s responsibilities included supervising student teachers and the university would not countenance an “avowed homosexual” in that role. Wilson’s appeal to the Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission went nowhere — “sexual orientation” was not a protected class. You could fire fags if you wanted to back then, and people did.

Wilson would abandon teaching and devote himself to community organizing, both in Saskatoon and Toronto, where he moved in 1982. He became an advocate of tenants’ rights, helped found AIDS Action Now, thrilled some (and disappointed others) when he ran as the NDP’s candidate in Rosedale during the 1988 federal election. He had to abandon the campaign when he became very sick with a form of pneumonia associated with HIV. By then he had a lover (they’d met in 1979), Peter McGehee, a writer (Boys Like Us) and performer (well known at the time as a founding member of The Quinlan Sisters, an a cappella trio described as “like the Osmonds without mom, dad and God”). McGehee would also be diagnosed with HIV.

I won’t give away the rest of their story, but it’s pretty classic romantic tragedy, a form which clearly attracted Geiss. He found the narrative compelling enough to abandon a strict talking heads, documentary approach (citing the Harvey Pekar biopic American Splendor as an influence). He engaged actors to play both Wilson and McGehee and did his best, on a budget of some $56,000, to recreate crucial scenes from the lives of both men. Jesse Owen, who plays Wilson with the help of some blond hair extensions (it was the era of shoulder-length), manages — perhaps simply by not being a very good actor — to convey something of Wilson’s diffidence, his vanishingly soft voice and the pinched disdain, which never really left him for the advantages his good looks might provide.

Geiss’s own background also drew him to the story. He, like Wilson, grew up on a farm and he says that his research for the film, “made me start missing it, made me nostalgic, especially with all the family stories about his doing things like trying to hypnotize chickens — there was so much there that only farm kids would do.” Geiss’s coming out stories couldn’t be more different from Wilson’s, though — several decades have made a huge difference, even in rural areas. “I only have positive memories,” he says. “I knew I was gay when I reached my teens, but there were no internal struggles. I didn’t do much about it till I got to the city, but it was always there. It was a bit awkward at first with my family, but everything is fine now.” He has a boyfriend with whom he’ll soon move, a little reluctantly it seems, given his Saskatchephilia, to Victoria.

Stubblejumper is apparently Canadian slang for a prairie grain farmer. It is also the name of the publishing company Wilson founded in 1977 (he would publish his own poetry and his lover’s novels under its imprint). Stubblejumper, the film, is something of a hagiography (Wilson’s sister Nancy, a real charmer who clearly worshipped him, is interviewed extensively), but it would probably have been unwise to try for anything more nuanced in 48 minutes (criticisms, inadequately developed, would just seem like sniping).

There are criticisms one might level at the film, if not the subject. It’s very clearly an early effort by a young director — Stubblejumper is only Geiss’s second documentary (preceded by Queen City, an exploration of the drag scene in Regina). Geiss relies too much on voice-overs of Wilson’s poetry, very much the product of the usual adolescent angst. Much of Stubblejumper will strike many viewers as overly sentimental and romanticized, the ending in particular wrapped in a nostalgic glow and a glimpse of farm boy heaven as a kind of stubble-jumping contest. There are technical problems that shouldn’t appear in a movie made by a film school grad — poor Tim McCaskell, interviewed on Wilson’s involvement with the Toronto Board of Education’s Equity Office, is so badly lit that you wouldn’t recognize him if you didn’t know his voice.

The film ends with a close-up of the AIDS Memorial in Cawthra Park, a long shot that finally closes in on Doug Wilson’s name. Geiss says he ended that way because “there are hundreds of names there and that means there are hundreds of stories that people will never hear unless we keep the stories going. I want people to leave my film touched in the way I was touched when I heard his story, the story of a man I never knew existed. He accomplished so much in his short life. It’s important to know that the people who came before us had an effect on how we live today, even though we can’t see it directly.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra