Queer activists are seething after a last-ditch effort to get the Senate to address shortcomings in the Liberal government’s bill to erase unjust convictions of queer people has ended in failure.

Bill C-66, the Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act, was introduced last November as part of the government’s apology for mistreatment of LGBT Canadians and passed through the House of Commons swiftly with minimal debate. It’s been with the Senate since December 2017.

The Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network calls Bill C-66 “fundamentally flawed.”

Activists had hoped that the Senate’s public security committee would fix sections that exclude large numbers of queer people who faced anti-gay prosecutions. But those hopes were dashed when the committee concluded its hearings with a recommendation to pass the bill unamended, but with “observations,” requesting the government take further action to address its shortcomings. It now awaits a final vote in the full Senate.

The bill would allow those convicted of a crime related to anti-gay persecution to apply to have the conviction expunged and deleted from any records. The current draft of the bill, however, only lists three types of crimes eligible for consideration: buggery, gross indecency and anal intercourse. Buggery and gross indecency were used against gay men until 1988. Anal intercourse is still a part of the Criminal Code, but the government has introduced a bill to strike it.

But activists and historians contend that most persecution of gay people happened under other sections of the Criminal Code, some of which still stand.

Queer historian Tom Hooper says that more than 1,300 men were arrested in bathhouse raids under the bawdy house charge between 1968 and 2004. He testified before the committee calling for the list of charges eligible for expungement to be broadened, to reflect the charges historically used to target queer Canadians.

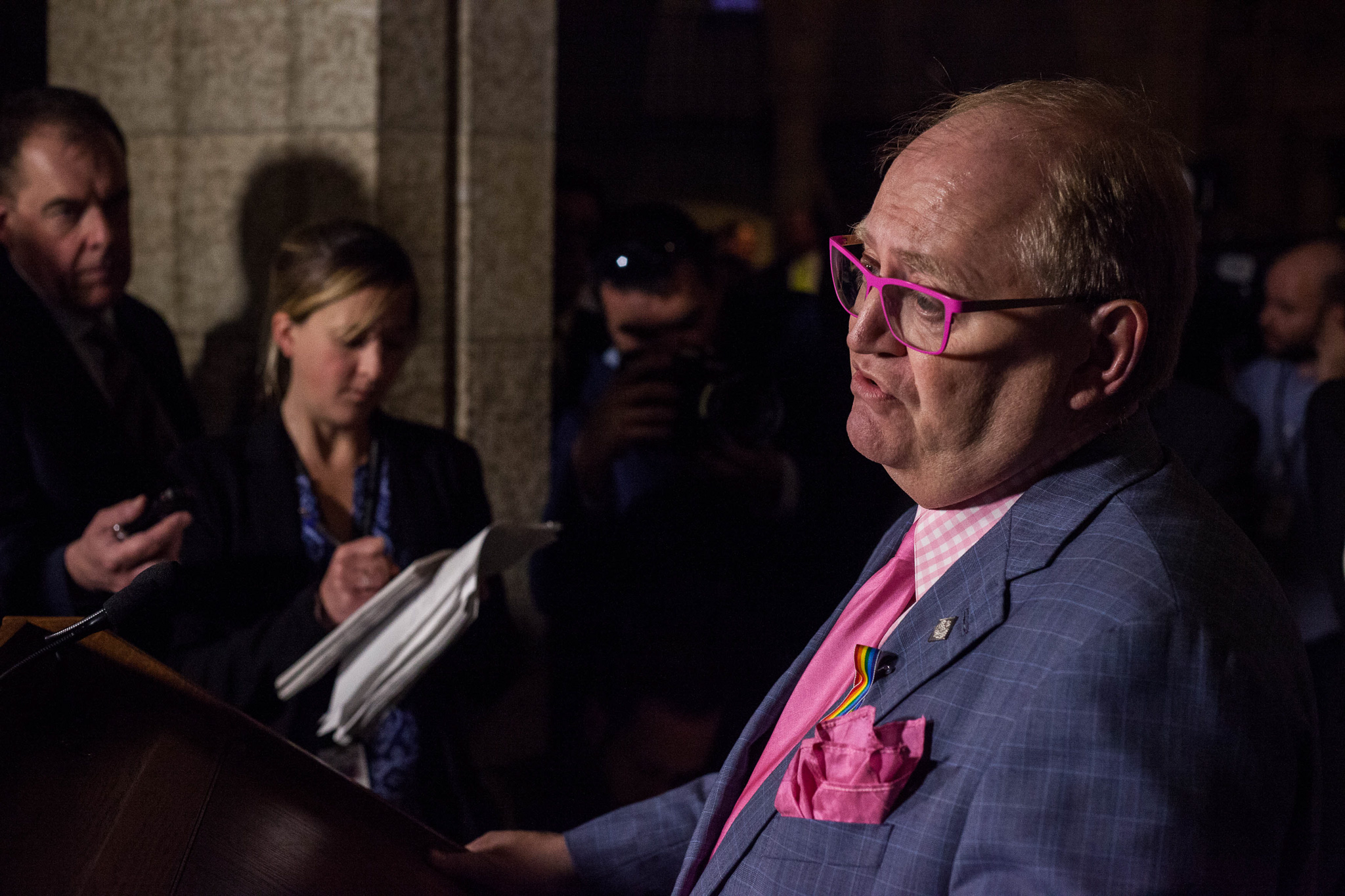

Credit: Courtesy Tom Hooper

In fact, during Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s apology to LGBT Canadians in the House of Commons last year, he specifically cited the bathhouse raids as unjust prosecutions.

“Discrimination against LGBTQ2 communities was quickly codified in criminal offences like ‘buggery,’ ‘gross indecency’ and bawdy house provisions. Bathhouses were raided, people were entrapped by police,” Trudeau said on Nov 28.

Queer lobby group Egale had demanded the government strike the bawdy house section of the criminal code and include it in an expungement bill in its Just Society Report released last summer. Lawyer Doug Elliott, who co-authored the Just Society Report, says the government refused to consult with Egale before drafting the bill.

“I had hoped that that was going to be done through a process of engagement with Egale and others in the LGBT community,” he says. “But the government decided to instead take more of a top-down approach.”

C-66 allows the government to make other sections of the Criminal Code eligible for expungement, but only if the section has been repealed by Parliament and if the crime was considered a “historical injustice.”

The government has no immediate plans to repeal the bawdy house section of the Criminal Code, even though Hooper says that convictions under the section have virtually disappeared since the Supreme Court’s Labaye and Bedford decisions.

Liberal MP Randy Boissonnault, who serves as special advisor to the prime minister on LGBTQ2 issues, says the bawdy house provisions may be dealt with in a future bill dealing with the sex work laws, but excluding them from the expungement bill was necessary because the law wasn’t directly targeted at gay men.

“As we look at expungement it’s important that we’re talking about same-sex consensual activity. That’s why the C-66 debate was clear on expungement. Bawdy house rules apply to same sex and opposite sex relationships,” he says.

In its observations on the bill, the Senate committee calls on the government to broaden the list of offences eligible for expungement, and calls on the government specifically to consult “with stakeholders and subject-matter experts to address other sections of the Criminal Code that were applied in a discriminatory fashion against the LGBTQ2 community,” including indecent acts, indecent theatrical performances, obscenity, nudity, operating or being found in a bawdy house, prostitution-related offences, vagrancy, and criminal HIV non-disclosure.

Angela Chaisson of the Criminal Lawyers’ Association told the committee that these types of charges were more common than buggery or gross indecency charges.

“Criminal lawyers know the injustice of having facially neutral laws targeted against specific communities, be they racial, ethnic or sexual. Police may, in fact, prefer to lay charges that are facially neutral because it allows that veneer of neutrality and it allows them to ward off any allegations of homophobia that would otherwise colour the prosecution,” she said.

Activists have also pointed out that the bill only allows expungement if the parties engaging in the criminalized sex were both over 16 years old — today’s age of consent — even though the historical age of consent was 14 until 2008. It effectively maintains a discriminatory age of consent for gay sex through the expungement process.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra