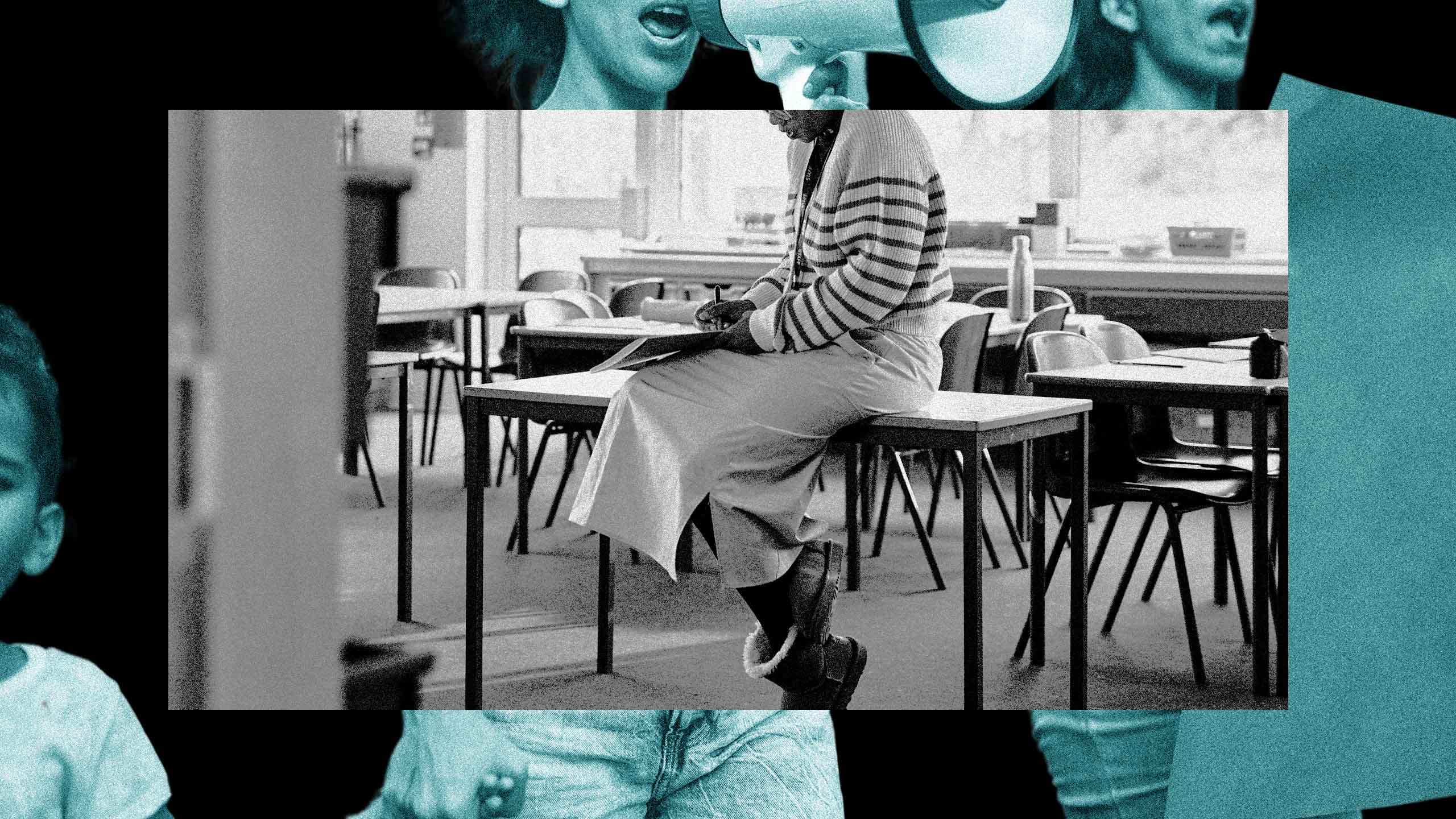

On a Monday morning last May, Taylor was getting ready for another week of work as a middle school teacher in Abbotsford, B.C., when they received a Facebook message from a former co-worker. They said they were sorry to see what was happening to Taylor on Twitter.

Confused, Taylor (whose name has been changed to protect their privacy) logged on to Twitter to discover that a photo of them had been posted by a prominent figure in Abbotsford’s “parental rights movement.” The photo showed Taylor standing between a Pride flag and a display for Pink Shirt Day, wearing a pink dress, patterned black tights, a black cardigan and boots. Pink Shirt Day, which began after an incident of homophobic bullying in Nova Scotia in 2007, is an annual event in Canada meant to raise awareness about bullying in schools.

The post also included a photo of a Pride flag on Taylor’s classroom door, and a “gender unicorn” graphic, developed by Trans Student Educational Resources, which Taylor had filled out about themself and posted next to their door.

The caption referenced Taylor’s drag name and asked if anyone would like Taylor to teach their children.

By the time Taylor saw the tweet, it had amassed over 50,000 views and hundreds of comments, which Taylor says included homophobic and transphobic slurs, the address of the school they work in and threats of violence. In the months since, the “parental rights” leader has made numerous social media and blog posts about Taylor, frequently using their photo, defamatory language and saying that Taylor should not be around children. He frequently tags accounts with hundreds of thousands of followers, like Libs of TikTok, Gays Against Groomers and Moms for Liberty.

“It’s definitely taken a lot of energy and zeal out of my teaching,” Taylor says.

They say the Pink Shirt Day photo is emblematic of how they used to show up to school: queer and proud. They say bright colours and a little bit of makeup were a normal part of their work attire. But now, Taylor says showing up as their authentic self feels “more dangerous.”

“It felt like I wasn’t just betting my own safety or my own mental well-being; it felt like I was betting my [fellow] staff and students’ safety as well,” says Taylor.

Nearly nine months after the 1 Million March 4 Children drew thousands of protesters to marches across the country, the parental rights movement is not only driving restrictive pronoun policies and other regulations, it is also impacting teachers’ working conditions, and emboldening harassment campaigns.

“What’s the least damaging option?”

David Popoff lives and works thousands of kilometres from Taylor, but he and his colleagues are also dealing with the impacts of homophobia and transphobia at work. Popoff is a musician and music teacher who has been working in public schools near Regina, Saskatchewan, for over 20 years. He also performs professionally with the Regina Symphony, splitting his time between both jobs.

Popoff says he has taught queer and trans students throughout his career. At the schools where he’s worked, the goal has always been to involve parents in discussions of new names or pronouns when the student feels it’s safe to do so.

“The people who are the safest for them might be their peers or their teachers, and it doesn’t necessarily mean that their parents are unsafe,” explains Popoff. “Sometimes it means that their parents are perhaps the most safe, and they want to make sure that they are comfortable with [their new name or pronouns] first before they put it to their parents.”

Popoff is a member of the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation’s Supporting Queer Teachers Committee, which provides a space for LGBTQ2S+ educators to connect and support each other. He says that the introduction of the province’s Parental Inclusion and Consent policies, which passed through the Saskatchewan legislature last year as the Parental Bill of Rights, prevents teachers from facilitating a discussion between students and their parents. Instead, teachers are simply sending home a form that asks for parents to give permission for their child to use different pronouns.

Saskatchewan’s Parental Bill of Rights requires parental consent before children under 16 can change their names or pronouns at school.

“Now teachers are put in a position where we’re looking at, ‘What’s the least damaging option?’ Which is awful,” says Popoff.

Popoff says that amongst teachers in Saskatchewan, there is a movement to not comply with the government’s orders. In October 2023, an online petition for teachers who refused to comply with the new Parents Bill of Rights in the province garnered over 100 signatures.

The Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation put out a statement criticizing the bill after it passed, acknowledging that it “places every teacher in Saskatchewan in a difficult position,” and that it was passed “without consultations with parents, school board members, school administrators, mental health experts or the STF.” Xtra contacted the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation for comment but did not receive a response.

Though Popoff hasn’t had to deal with personal attacks or harassment campaigns, he’s heard of other teachers in Saskatchewan who have dealt with harassment from the local community after rumours spread about what’s being taught in the classroom with regard to gender and sexuality.

“It can be really tricky to create the balance between having the people in your community comfortable with what’s going on in a classroom, but also having your students trust you”

Casey Burkholder, an associate professor at the University of New Brunswick, who studies gender and sexuality curriculum, said a common theme in her discussions with teachers is fear about parents’ and community members’ perceptions of sexuality education.

As part of a research project called Sexuality NB, Burkholder regularly hosts workshops for public school teachers to discuss the supports and barriers to teaching comprehensive sexuality education in the province.

“It can be really tricky to create the balance between having the people in your community comfortable with what’s going on in a classroom, but also having your students trust you,” says Burkholder.

Sexuality NB was scheduled to wrap up last year, but because of the government’s changes to Policy 713, which include requiring children under 16 to have parental consent before they can change their name or pronouns at school, Burkholder says the project has continued.

“Some of the things that we’ve been finding so far is that policy 713 itself gives teachers the sense of not being supported in their work to affirm queer and trans youth,” she explains.

Burkholder says teachers have told her that the policy change has made it difficult to gain students’ trust because “there’s this fear that a teacher will out a student to their families without their consent, which is the consequence of the revised policy.”

As part of her research, Burkholder and her team conducted a survey of 412 elementary, middle and high school teachers in the Anglophone public school districts in New Brunswick that found that the vast majority of teachers had received no training to teach sexual health education. As a result, Burkholder said many reported feeling uncomfortable teaching the subject.

The government’s changes to Policy 713 include a pause on third-party organizations teaching sexual health education in the province.

She says a lack of training and support from higher-ups in education are causing teachers to feel “demoralized.”

“I had a teacher just the other day say that they felt supported in their school, by their admin, but that they didn’t feel supported by the higher-ups, including the premier and the education minister,” says Burkholder.

Hazel Woodrow is a researcher and educator with the Canadian Anti-Hate Network. She leads workshops with teachers across the country focused on identifying and protecting youth from racist, sexist and anti-LGBTQ2S+ harassment and violence.

Woodrow says that over the past year, teachers have approached her with concerns about anti-LGBTQ2S+ hate from their communities. She recalls one teacher in particular coming to her in tears because of harassment from parents and a lack of support from administrators.

Woodrow is concerned that putting teachers in a position where they are expected to do something they know could have very negative consequences could cause what sociologists call “moral injury.”

Moral injury refers to the damage done to someone’s conscience when they perpetuate or fail to prevent something that goes against their moral code. Moral injury has been studied in veterans of war and in healthcare workers who worked through the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I’m very worried about that, and I’m worried about what that has the potential to do to education systems across the country that are feeling increasingly precarious.”

Teachers in Florida, where the Republican government led by Ron DeSantis has introduced restrictive “Don’t Say Gay” bills that ban instruction on sexual orientation or gender identity through eighth grade, and allow parents to sue teachers who are suspected of doing so, have reported leaving the profession in response to homophobic and transphobic policies.

Taylor says that while their colleagues and the administrators at their school have been supportive of them, they would like to see more support from people with power in the education system. They say they think there is a lack of clarity when it comes to policies about community harassment and protests around schools, and the work of tracking the harassment they have been subjected to online has taken a toll on their mental health.

Taylor hasn’t had much success in reporting the posts targeting them as harassment or hate speech on X, and says the police told them that they couldn’t do much about online harassment. They have filed a report with WorkSafeBC, the province’s workers’ compensation board, and explored taking legal action and filing a human rights complaint.

Taylor says that a lawyer told them they have a strong defamation case, but that the “parental rights” leader would likely respond with an anti-SLAPP lawsuit. Anti-SLAPP laws—anti-strategic lawsuits against public participation—were created to prevent individuals or organizations from launching lawsuits intended to silence their critics.

In December 2023, an Ontario court ruled against an individual who attempted to use anti-SLAPP litigation to argue that referring to drag performers as “groomers” was public interest speech. The lawyer told Taylor that this precedent means they would likely win their defamation case, but they would not win their court costs, which were estimated to be between $5,000 and $10,000.

They have since filed complaints with the BC Human Rights Tribunal, and after eight months, they were told that their complaint was moved to the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. They will likely have to wait another nine months for an update.

Taylor says they are watching what’s happening in New Brunswick and Saskatchewan, and are curious to see if teachers unions will step up to protect teachers who refuse to abide by the pronoun policies.

“There still is strength in unions, and I think this is a really good time and place to wield that strength and authority in a good way,” says Taylor.

In New Brunswick, the provincial government has argued against unions representing teachers, school psychologists and support staff from joining a legal case against the pronoun policy. The province’s lawyer, Clarence Bennett, says the case is about students’ rights, not the rights of teachers, and that unions have nothing to add to the case.

Justice Richard Petrie has since denied the unions’ request to join the case, saying that the province’s objections influenced his decision. The judge argued that the pronoun policy is a “workplace issue” for staff that should be dealt with through labour adjudication. The unions have already filed policy grievances against the policy changes.

Groups advocating for LGBTQ2S+ rights, advocates for Indigenous Two-Spirit people and two groups supporting the policy changes were allowed to join the lawsuit.

Feeling demoralized, but still striving for safer spaces

Burkholder says that though these changes are weighing heavily on teachers, many recognize that home may not be a place where students who are exploring their sexuality or gender identity feel comfortable being their true selves. Some teachers are inspired to strengthen the spaces at school that still affirm queer and trans students.

“I would say, in general, folks are feeling demoralized,” says Burkholder. “But still, there’s this desire to make school a better space for students and also to affirm the spaces that students are creating for themselves.

“The GSA space is emerging as a really important space for people to relax and be themselves,” says Burkholder.

Along with his work on the Supporting Queer Teachers Committee, Popoff has helped with Genders and Sexualities Alliances, sometimes called Gay-Straight Alliances (GSA), at the two schools where he teaches. He said that even though his school district has been supportive of the GSAs and even hosted a GSA summit, shrinking budgets put these supports and spaces at risk.

The Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation is currently in bargaining with the provincial government to negotiate a new collective agreement, which guides how much teachers are paid and their working conditions. One of the priorities for the federation is addressing the number of students in a class and the support available to them.

Popoff worries that with less funding available for supports like GSAs, and student support workers stretched thin and focused on students who need intensive support, fewer kids will get the support that they need.

“The further we go down this path of less funding, [more] inflammatory policies, these kinds of things, the harder it gets for those kids, especially the kids that are in that middle ground [of needing support],” says Popoff.

On April 8, as part of strike activities, Saskatchewan teachers began work-to-rule, meaning that any work that happens outside of school hours is put on hold until a deal is reached.

Popoff says that because GSAs fall outside of school hours, they are impacted by work-to-rule.

“Work-to-rule definitely shuts down a lot of things that really engage students in our schools … some really are integral to student well-being, like a GSA.” This year, he says, “with all the uncertainties around bargaining, the pronoun policy and general teacher workloads,” he feels as though fewer GSAs are running. “Students are wary of participating, teachers are unsure of how they’ll be viewed in this current climate,” he says.

Still, he’s supportive of any methods that could ultimately result in securing more protections for both teachers and students.

“It’s our working conditions, but it’s also their learning conditions,” he says.

Taylor wears many hats at their school, and in all of their roles, they strive to help and advocate for those in need. Taylor says that since the harassment started, they felt themselves “go back into the safety of a cismasculine role,” a privilege they acknowledge not everyone has.

“I cultivated this invisible personality so that I would not be bullied,” Taylor explains. “I feel like as soon as I stepped out into my queerness and my queer joy, that I got this big smackdown.”

They said that being “visibly queer” at work was, in part, to show their students that queer people can make it to adulthood and thrive.

“You can be you, however that is, and make it,” says Taylor. “But it just feels more and more dangerous to even be that kind of role model.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra