On a Sunday afternoon in Crown Heights, a group of queer Brooklynites gather in a storefront on a street corner for an Indian-American feast.

Urja Dwivedii, a 26-year-old artist, arrives at the Nonbinarian Bookstore with a glass Tupperware container. Each guest at the event was instructed to bring a dish from a cookbook by a queer author. This month, the group is celebrating a cookbook by non-binary author Preeti Mistry, and Dwivedii is bringing fruit chaat.

“I’m a little shy and can be socially anxious,” says Dwivedii, who is returning after attending their first queer cookbook event here last month. They dole out servings of their dish, a fruit salad swirling with melons, yogurt and chutney, while another patron serves a salad with cucumber and fennel.

Dwivedii mentions that they prefer the idea of meeting other queer people in a bookstore rather than a bar. A bookstore “is an easier way to access that community that doesn’t feel overwhelming,” they say. “It kind of lets me do it at my own pace.”

The potluck is one of many events organized inside the Nonbinarian: a trans-owned shop offering an entirely queer-focused inventory, and a packed calendar of queer, mostly sober events. On their website, founder K. Kerimian says, “We especially want our store to become the ‘third place’ our community deserves but does not have.”

The concept of a “third place” was originally coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his 1991 book The Great Good Place. Oldenburg argued that informal gathering spots for people to meet outside the home and workplace in urban spaces like parks, bars and coffee shops were essential for a community’s flourishing.

Historians argue that queer third places—social gathering spots for LGBTQ2S+ people—are especially important as they have provided an outlet for queer people to find community long before queer liberation movements found mainstream acceptance. And, like the Nonbinarian’s queer cookbook club in Brooklyn, queer third places have taken on different forms over the years that extend beyond just nightclubs and bars.

Queer third places “have really run the gamut of history,” says Jack Jen Gieseking, a psychologist and researcher of queer history and culture. Gieseking is the author of A Queer New York: Geographies of Lesbians, Dykes, and Queers, which documents queer and trans history in the city.

Gieseking defines a queer third place broadly and loosely. “It’s really these kinds of places that queer people either own or manage or staff or are patrons of,” Giesking says. The factor that makes a place queer can range from the people who run and frequent it, to design elements in the space like the presence of Pride or trans flags.

Alix Genter, an academic editor and expert of lesbian history, says queer spaces in New York City—long considered the centre of the North American LGBTQ2S+ movement—started building steam after the Second World War. Her dissertation describes how the war led to more people migrating to urban spaces and socializing with the same sex either for factory work or in military service, which allowed the first few queer spaces to flourish.

“There were a lot of places that were just, like, neighbourhood dive bars that, maybe, the back door would be open for queer women and men,” Genter says of postwar New York. The initial queer bars in New York were also often more prevalent in Harlem, where many queer women attended neighbourhood bars founded by the Black community, who were also facing segregation.

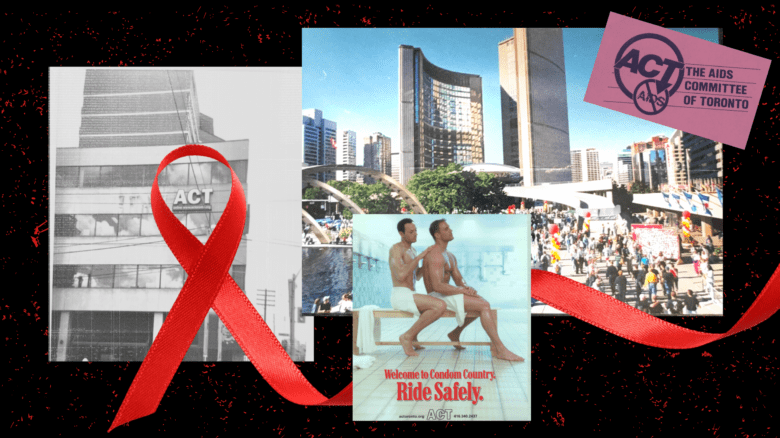

The 1969 Stonewall Riots gave way to a global rise in queer activism. With rising visibility of queer people in everyday life, more bars, bookstores and clubs that openly catered to queer clientele emerged across North America.

In Toronto, the Glad Day Bookshop opened in 1970, which has gone on to be the oldest continuously run LGBTQ2S+ bookstore in the world. In San Francisco, the Twin Peaks Tavern became the first gay bar in the country to uncover their plate-glass windows in 1972, which allowed people on the street to be able to peer in and see the patrons inside.

Queer third places extended beyond major cities too. Joshua Burford is the founder of the non-profit Invisible Histories, which documents queer history in the American South. He says that queer third places in the South began with “guerilla-style” gay bars as early as the 1920s, where queer people would take over straight bars on certain nights, even if they were never explicitly advertised.

The 1970s led to more visibility in the south too. Burford says that in 1975, the city of Birmingham had 15 classified gay bars, and almost every major southern city had a gay bar beginning in the 1970s. Founders of gay bars in the Rust Belt and American South would make use of extra land to set up shop in more rundown parts of town. Given the low population density in the South, the bars would also serve clientele from a much wider geographic radius compared to their coastal city counterparts.

“And they had the lives of mayflies,” Burford jokes, explaining how many gay bars in the South often closed after just one or two years of operation.

These bars weren’t perfect either. G. Samantha Rosenthal, who wrote Living Queer History: Remembrance and Belonging in a Southern City, a book about her experiences living as a queer person in Roanoke, Virginia, adds that early many queer bars in the city were racially segregated, either explicitly or in practice. “You have one geography of queerness for white Roanoke, and one for Black Roanoke,” Rosenthal says.

She also mentions how the strict rules against crossdressing—many of these gay bars were under the radar—prevented many early queer bars from being welcoming to trans people. “They were all really male-dominated spaces,” Rosenthal explains.

But bars weren’t the only way queer southerners connected. “From the 1970s, the largest gay organization in the United States was the Metropolitan Community Church [MCC],” says Nikita Shepard, a researcher of queer history from Columbia University by way of Raleigh, North Carolina.

A Mississippi preacher named Troy Perry founded the MCC after coming out and being rejected from his church and community. Perry started the church in his Los Angeles living room and eventually developed branches across the American South.

These churches became gathering spots for queer people in the South, especially in Black communities, Shepard explains, for whom the church was often a more central part of life than for many white communities.

Unlike bars or clubs, MCCs allowed queer southerners the chance to gather in more non-commercialized, sober-friendly places, and they allowed LGBTQ2S+ Christians to remain connected to their faith. Plus, Shepard says, laughing, it’s the American South: there are already churches everywhere, so the infrastructure was already there.

During the 1970s, as the Southern queer community experienced unparalleled visibility, so too did they experience increased vulnerability, Shepard explains.

There was a wave of arson attacks that particularly targeted LGBTQ2S+ institutions across the American South. Shepard mentions an arson attack in 1973 that killed 32 people at the UpStairs Lounge in New Orleans, in which almost all of the victims were MCC members. Afterward, Troy Perry flew out to Los Angeles and held a rally to console the surviving victims of the attack.

Shepard credits the arson attack as one of the “unfortunate reasons” why there are fewer visible queer third places in the South today.

In addition to churches, Erik Piepenburg, author of the new book Dining Out: First Dates, Defiant Nights, and Last Call Disco Fries at America’s Gay Restaurants, says that queer-friendly restaurants were another type of queer third place across the country that served a wider clientele by not serving alcohol.

“Generally anyone can go, and that includes gay youth who are too young to get into gay bars,” Piepenburg says. He explains that restaurants also attracted more elderly queer people than gay bars because it was easier to have a conversation without noise.

While Piepenburg didn’t gather exact numbers while writing his book, he estimates that based on phone books and travel guides, there were thousands of restaurants across the country in the 1980s and 1990s that specifically catered to the queer community. Like queer churches, many of them extended far beyond San Francisco or New York.

In Austin, Texas, Dinty Moore’s Café and Bar, a kosher deli with a bar at the back, developed a reputation as being a particularly queer-friendly establishment since the 1950s. Lesbians in Bridgeport, Connecticut, in the 1970s gathered at Bloodroot, a feminist vegetarian restaurant that still serves tofu salads and veggie burgers today.

But the golden age of queer third places couldn’t last forever, Gieseking explains.

Beginning in the late 1990s, many queer spaces began to close up shop in major cities. The cost of property skyrocketed in New York City between 1996 and 2006, which Gieseking explained made it unaffordable to open new institutions in the city, including queer gathering spots.

There were also some broader trends that made queer third places less of a necessity nationwide. Medical advancements reduced the need for organizing around AIDS, and more people began adopting sober lifestyles beginning in the early 2000s, driving down the demand for queer bars in particular.

Social progress was never an even road—cis white gay men had a far easier time assimilating into the mainstream than trans people or queer people of colour—but Gieseking says increased acceptance for LGBTQ2S+ people among the general public also lessened the demand for places catering especially to queer clientele.

“Oh my god, we have a shelf,” Gieseking jokes, referring to how LGBTQ2S+ sections in bookstores have replaced many in-person stores.

More recently, Gieseking points to how dating apps like Grindr and Hinge have made it easier for queer people to meet each other virtually. Nonetheless, Gieseking says that queer third places serve a critical social function that apps cannot replace.

“ These third places are really great because they don’t just like help us find, like, our next hookup or the love of our life,” Gieseking says. “We also find our proctologist and our next job.”

Gieseking credits pandemic-fuelled angst for the comeback of queer third places, especially among Gen Z. After years of being cooped up at home, many young queer people are looking to make more in-person connections as we move toward a “ not as intense” stage of the pandemic, Gieseking says.

They also credit TikTok for exposing younger generations to queer history. Accounts like @your_lesbian.mom have shared with young people the trials of growing up queer in the 1980s, while more history-focused accounts like @rainbowhistoryclass have provided short videos with LGBTQ2S+ history lessons.

“You have all these people talking about queer history on TikTok, and the youth are listening to their elders in record numbers,” Gieseking says. “They’re hearing about how great these spaces were and people bemoaning the absence and loss of them, and wanting to re-create them.”

Back at the Nonbinarian Bookstore—a present-day third place, sandwiched between a bar and a café on a residential block in Brooklyn —Dwivedii’s fruit chaat has attracted the attention of some neighbourhood children. The kids come inside the bookstore to chow down on some Indian food, while Dwivedii continues their conversation with me outside.

Dwivedii says they agree with Gieseking’s observation that social media helps young people find out about queer spaces. In fact, they had met the person who invited them to the queer cookbook event through a version of Bumble designed for people seeking friendships.

Dwivedii, who attended most of their college experience in Savannah, Georgia, online, say they had been craving in-person queer gatherings since graduating and moving to New York City in 2022. Social media and dating apps, while useful as a starting point for meeting people, could not replace the necessity of an “IRL” third place, they tell me.

“ I feel like there’s so many screens already involved in my life,” they say, smiling. “I don’t want to have a relationship through a screen.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra