EDITOR’S NOTE: This is a cautionary tale about internet scams. Everywhere you look online there are traps to catch the unaware and the vulnerable. The impacts of scams targeting the LGBTQ2S+ community can go beyond putting the finances of victims at risk. There is a special cruelty present in scammers who prey on some of the most vulnerable people in the queer and trans global community, especially activists fighting for change. If you think you or someone else you know is being targeted in Canada or internationally, contact the Canadian Anti-Fraud Centre online or by calling 1-888-495-8501.

Solomon Atsuvia thought he was going to cross Canada off his bucket list. When he saw a colourful flyer for an Ottawa “LGBTQ+ Rights Summit & Conference” on social media late last year, Atsuvia imagined himself converging with fellow activists this July “to connect with the global community, to build some networks for purposes of advocacy,” he says.

The native of Ghana, who now lives in South Africa, has attended conferences around the world similar to the one promised in the online post. They helped open doors for his work with Rightify Ghana, an advocacy group for queer and trans people in the West African nation.

For international front-line activists, attending a Canadian LGBTQ2S+ conference can represent a career milestone or a personal dream. This can be especially true for those in one of the 65 countries, Ghana included, that criminalize same-sex relationships.

Advocacy work in these countries is high risk and the people who do it are often isolated because of their identity. Conferences represent fellowship, learning and, even, acceptance. They can also offer a chance to enter Canada on a legitimate visa and apply for asylum to leave behind a nation where queer and trans people live in constant danger.

Travelling overseas for such an event can pose a significant cost and that alone can be an insurmountable barrier. In some countries, Ghana included, average monthly salaries are a fraction of what workers make in Canada. The average Ghanaian public service employee, for example, earns about CAD $240 a month, about 1/20 of an average Canadian salary.

It’s common for groups organizing conferences in wealthier countries to offer scholarships to reduce such inequities and help international guests attend. Atsuvia had been granted financial assistance for similar events before. With that in mind, he emailed the address on the social media post to inquire about the “exclusive sponsorship opportunities” organizers promised.

He learned full sponsorships were no longer available, but a limited number of partial ones were to be awarded on a first-come, first-served basis. Atsuvia alerted some of his teammates at Rightify Ghana. He and five colleagues applied. One was told in an email from conference coordinator “Thomas William (She/Her)” that the limit of four sponsorships per organization was being increased to five for Ghanaian and Ugandan applicants “in recognition of the extreme challenges faced by the LGBTQI+ community in these countries.”

Four of the six Rightify Ghana applicants were quickly offered partial sponsorships, covering round-trip airfare, accommodation and “basic expenses.” They each needed to cover only a CAD $396 discounted registration fee, according to emails reviewed by Xtra. Atsuvia says he and his colleagues immediately began raising money—some taking out loans—to make sure they could attend.

In an email to Atsuvia, William commented, seemingly with a touch of passive aggression, that they should apply as a group instead of individually in the future to create less processing work for organizers. Atsuvia and another colleague apologized for wasting her time with the extra work—but they shouldn’t have. It was the Rightify Ghana team’s time that was being wasted with lengthy email exchanges and a detailed application process. They just didn’t know it yet.

With the request for payment weighing on his mind, Atsuvia started asking questions about the event’s legitimacy.

Something seemed off

One particular detail left Atsuvia perplexed. The conference was willing to cover the costs of return flights—a round-trip flight from Johannesburg, close to where Atsuvia is studying law, to Ottawa, costs about CAD $2,600—but not the registration fee. Typically, in his experience, partial sponsorships pay for all expenses but flights.

“Why can you absorb that, and you can’t absorb a registration fee of $400?” Atsuvia says.

Suspicious, he reached out to Ottawa-based reporter Dylan Robertson, who, Atsuvia says, advised him that the event didn’t seem legitimate.

Atsuvia later learned that others in Canadian non-profit circles were quietly wondering about a similar Montreal-based conference advertised last year—again targeting international LGBTQ2S+ delegates.

This year alone, the same conference organizers have advertised sponsorship opportunities for international participants to attend an “Annual General Meeting & Workshop” at the “Marriott Conference Center” in November and for an in-person “Global LGBTQI Empowerment Week” next January

In Xtra’s investigation into these events, we have discovered the advertisements are part of a scam victimizing people who work to advance queer and trans rights. The group’s website describes an organization with an ambitious scope of LGBTQ2S+ activism, including grants for community organizations and assistance for asylum seekers and refugees. It claims the group has donated millions to LGBTQ2S+ causes and is funded by the federal government of Canada and the Ford and Rockefeller foundations, among others.

The scam begins to unravel

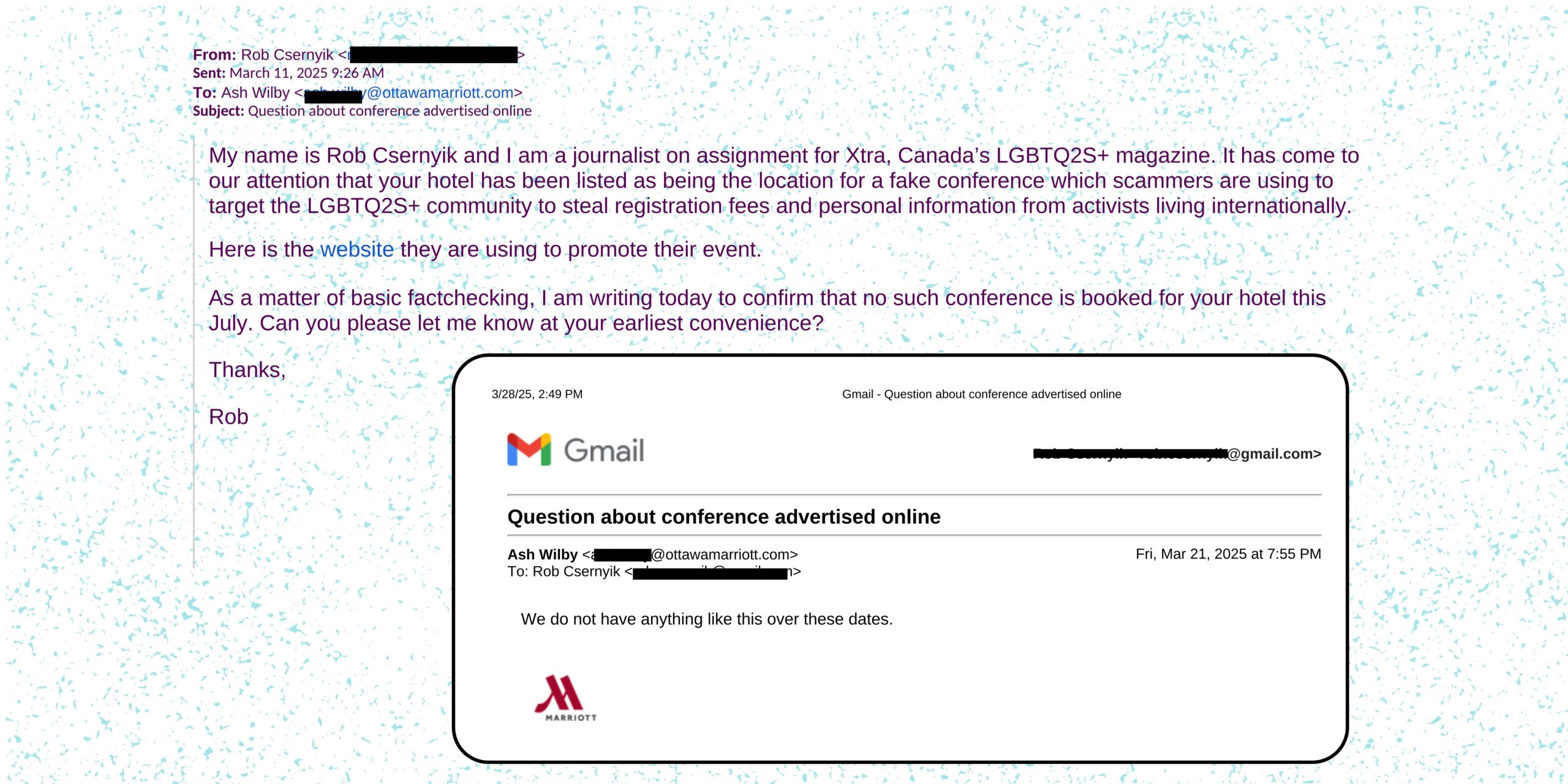

These bold claims are easily disproved. A spokesperson for the federal government told Xtra that the Ottawa conference was not assigned a registration number, which is necessary to grant visas to international conference attendees. The Ottawa conference was advertised on Facebook and on the organizer’s website as taking place at the Marriott Hotel. Xtra contacted the hotel and a staff member confirmed the conference was not booked there.

Xtra was also shown a letter sent to a registrant of the Montreal human rights conference, which included a special event code. According to an Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada spokesperson, the code does not correspond to a registered event. In other words, it was a fake.

Looking deeper into the organization’s online presence, photos on its Facebook page were from events not associated with the group. There were images from a legitimate 2024 LGBTQ2S+ conference, an Australian city council meeting and a British Columbia university. Some photos had been digitally altered with logos added and some identifying details blurred.

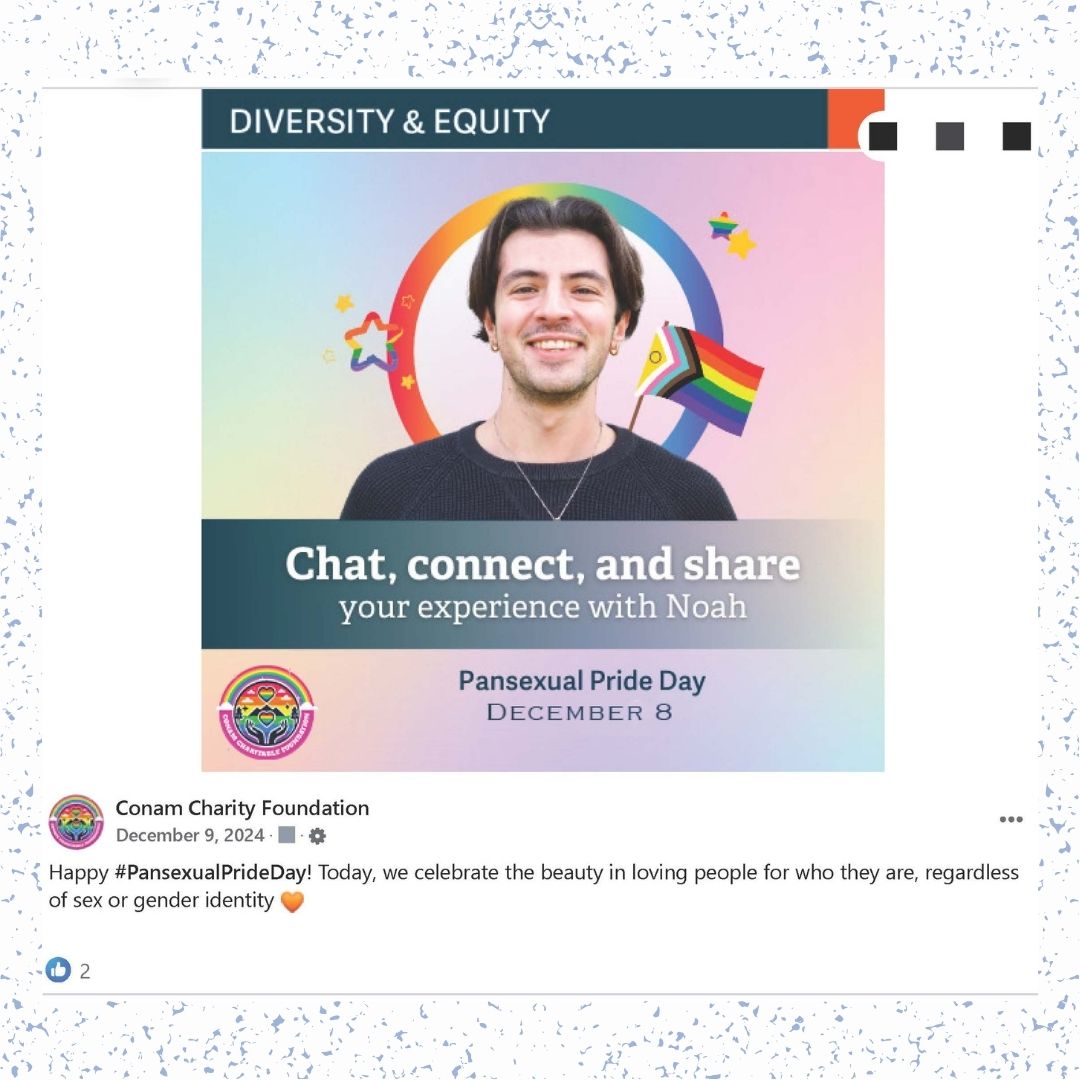

The scammers used a real charity to create their fictitious event and, in doing so, created another victim of their deceptions. The logos on its advertisements use the name Conam Charitable Foundation (CCF), which is a genuine registered Canadian charity that has been active for nearly 20 years.

The CCF supports other charities by facilitating donations of flow-through shares. It is not an LGBTQ2S+ focused charity and, until contacted by Xtra, had no idea its name was being used in the scam.

Steve Roth, a director of CCF, says neither he nor his colleagues are planning an Ottawa conference. The CCF lists a Thornhill, Ontario, residence as the charity’s address. That address remains listed on the scam organization’s website and Facebook page.

Furthermore, Canada Revenue Agency’s page for the real CCF doesn’t list a website for the charity. Roth says along with not having a website, the real CCF also does not have social media accounts or offices outside Canada.

“This is very disconcerting,” Roth said via email, adding he would try to have the website and Facebook page shut down. Later, the Facebook page disappeared for a few weeks but then came back online.

Xtra was able to trace some of the emails and online postings about the fake event to accounts in Tanzania, an East African nation of about 67 million where financial prosperity and LGBTQ+ rights are in short supply.

Read Solomon Atsuvia’s full email chain with the scammers as provided to Xtra.

The scam surfaces in Pakistan

Farhan Wilayat Butt, a Pakistan-based human rights activist with an interest in religious minority and disability rights, wanted to attend the 2024 event in Montreal. Though not LGBTQ2S+ himself, he’s also does advocacy and support work for trans rights. He, like Atsuvia, saw a social media post and was enthusiastic about combining his passion for human rights activism with a trip to Canada.

“I belong to a lower middle-class family, and I cannot afford air travel from Pakistan to Canada,” Butt emailed the event coordinator, requesting full sponsorship. He was awarded one and asked to pay CAD $445. “That amount is roughly half of my monthly salary,” he tells Xtra.

This is a letter the scammers sent to Farhan Wilayat Butt, inviting him to speak at a conference. Some information has been redacted to protect Butt’s privacy.

The person who responded to Butt identified themself as the conference co-ordinator and signed the email “Benjamin Logan (She/They).” In the email chain, they instructed “Shany,” “head of finance & support,” to create a payment link for Butt either using a digital wallet app called Skrill or the Pakistani financial institution Meezan Bank.

A bank holiday was going to delay Butt’s payment, so it was suggested that he use the wire transfer services MoneyGram or Western Union to send money to one of Maple Diversity Alliance’s “worldwide offices.” This included one in “East Africa,” the region where Tanzania is located.

Butt says when he visited a Western Union office to send the money, staff demanded several documents before they would complete the transfer. In his next email to event organizers, he sounded weary and exasperated.

“These visits consumed half of my working hours (as I took half-leave from my work) but I couldn’t make [the transaction] due to their mandatory requirements,” Butt wrote.

Organizers suggested Butt send money directly to an individual through MoneyGram.

“Our Regional head in Tanzania will be able to provide his government ID so you will find it easy to send,” the email said. “I am sure it won’t be difficult. You can tell them you are sending it to a friend.”

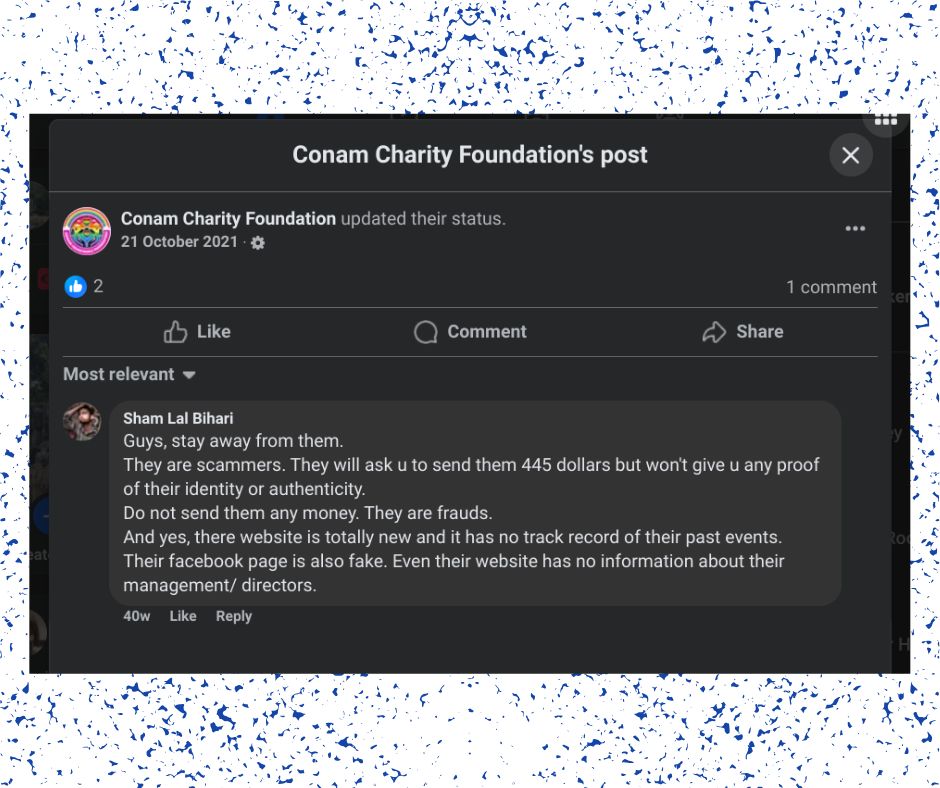

This was concerning to Butt. He did further research and noticed the recent creation date of the website that advertised the conference. The name of the Facebook page had also recently changed. That, plus a lack of photos and videos from past conferences, made Butt wonder if he should move forward with payment.

Victims can lose more than money, much more

Bhupendra Acharya, a postdoctoral researcher at Germany’s CISPA Helmholtz Center for Information Security, says there’s more at risk for scam victims than losing money. Their data may also be sold on the dark web, the untraceable portion of the internet accessible only through specialized software.

They may also become victims of identity theft. The fake CCF organizers asked activists registering for their events for supporting materials including photos of passports, non-profit registration details, letters of endorsement, signatures and banking information.

Atsuvia and Butt are unaware of their information being used maliciously—yet.

Internet scams are big business. They steal about $1 trillion U.S. globally each year. In developing nations, the Global Anti-Scam Alliance considers the impact to be so large that it can generate the equivalent of several percentage points of national GDP.

No formal trend of global scams targets the LGBTQ2S+ community specifically, but the advertisements for the Montreal and Ottawa events play into two common scam tropes: charity fraud, where a non-profit’s identity is used for financial benefit, and fake conferences. These are common, and they are now being used to target LGBTQ2S+ people internationally.

Conference scams a common hazard

Tyrone Curtis, a postdoctoral fellow and public health researcher at the University of Victoria, says conference scams are a common hazard for academics and researchers.

“We get so many emails from conferences that are predatory,” he says. Often, they entice with offers to present research. Curtis says he’s received many invitations to speak at conferences irrelevant to his area of expertise.

Curtis, who first made Xtra aware of the scam, noticed text on the fake CCF site appeared to be lifted from LGBTQ2S+ organizations such as Stonewall, a queer and trans charity based in the United Kingdom, and a relatively niche Canadian queer health research centre.

He contacted Xtra about the website, concerned at first that the real CCF was trying to make money off queer and trans communities, despite LGBTQ2S+ causes not being the focus of its work.

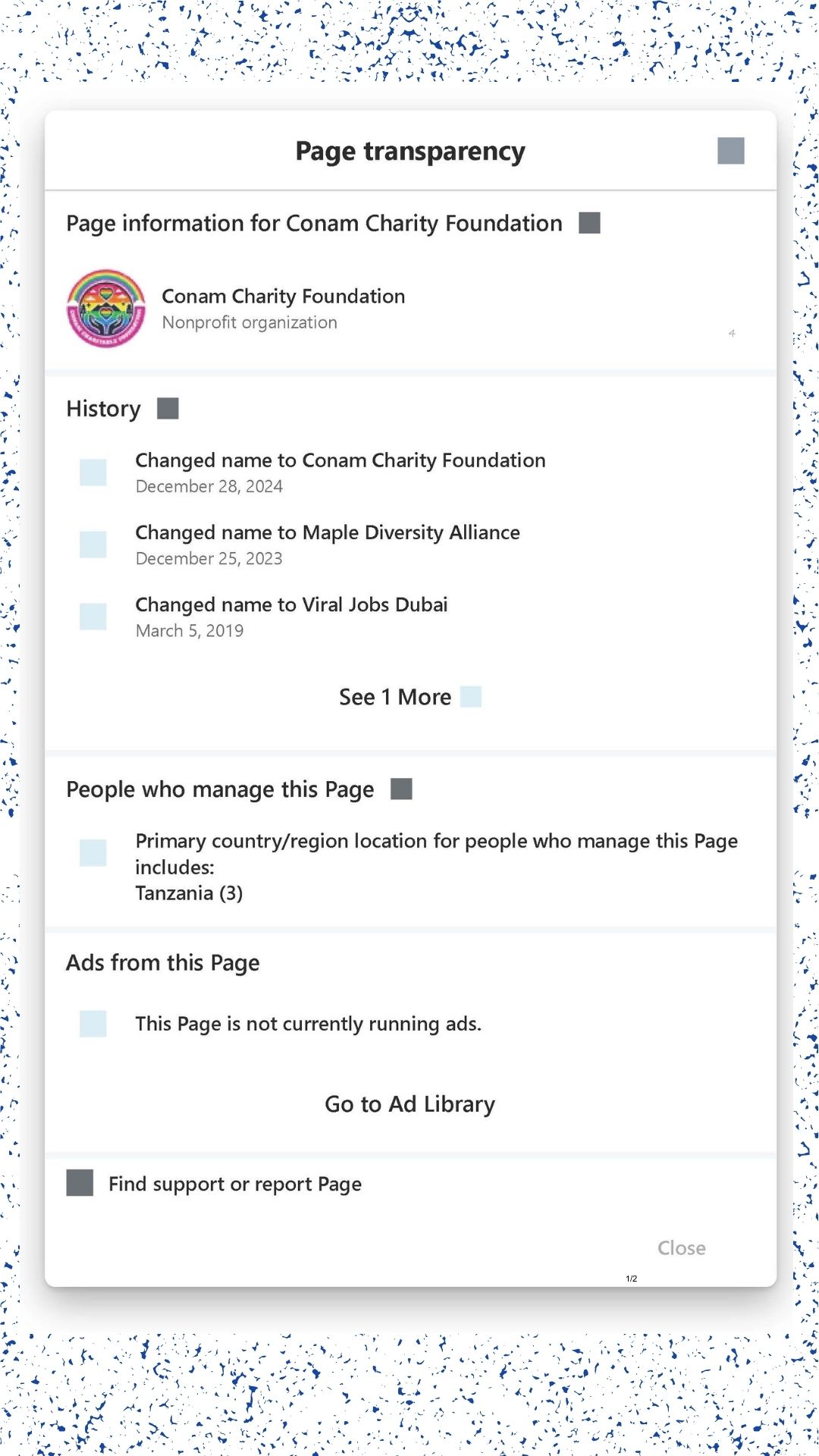

The scam Facebook page took on the CCF’s name in December 2024, the same day the fake CCF website’s domain was registered. Before that, the Facebook page, created in October 2017, bore the names Maple Diversity Alliance and Viral Jobs Dubai. Acharya says scammers often buy pre-populated social media profiles to help give them a more legitimate appearance.

The Facebook page used to promote the fake events does not list the names of its owners. Despite presenting as a Canadian organization, the Page Transparency information lists Tanzania as the primary country location of the page owners. According to Facebook, this is “determined by someone’s activity on Facebook products,” including Messenger, Instagram and WhatsApp.

The challenges of trying to take action

Doug Kerr, executive director of Dignity Network Canada, a network of organizations interested in human rights for LGBTQ+ people globally, forwarded emails to Xtra that show that LGBTQ2S+ activists in Canada expressed concern last year about advertisements for the Montreal event. Xtra learned complaints were made, formally and informally, to police and federal government departments.

Some of Kerr’s emails mentioned reporting concerns to federal government departments as well as Montreal police and the Sûreté du Québec (SQ) provincial police. Simon Gamache, executive director of Fierté Montreal, was part of the email chain and spoke informally with contacts at the police forces who advised him to make an official complaint. “I informed some folks who had brought [the conference] up of this necessary step to assure police help, but I am unsure if a formal claim was sent,” Gamache says.

Xtra sent written questions asking if Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada, Women and Gender Equality Canada and both police services had received complaints about the events. Xtra received no answers to its specific questions. However, an SQ spokesperson did offer an explanation via email: their system doesn’t allow them to isolate that information, but such a complaint might have been counted among the service’s 1,634 internet fraud dossiers in 2024.

Kerr later shared emails with Xtra confirming that representatives from WAGE and Global Affairs Canada were aware of the scam. “You raise important points about the harms this organization/conference could have both on activists sending money and on the overall work that we all do,” the WAGE representative responded to Kerr, in part. The representative from GAC referred to the situation as “strange and worrisome.”

The fact the scam keeps resurfacing and promoting different events suggests that complaining to officials has no effect. According to Xtra’s investigation, no organization, whether a Canadian LGBTQ2S+ non-profit, or a police or government department, has publicly released a warning about this scam.

Kerr knows that people in multiple countries asked about the legitimacy of the events. This year, a Thailand-based member of Dignity Network’s global advisory board asked for details after hearing about it from activists in several Asian countries. Still, Kerr expressed concerns that openly discussing the issue will cause some people to look negatively on legitimate work being done in the sector.

“What we do is really important in terms of strengthening the global [LGBTQ2S+] movement and showing Canada can be a support,” he says. “Stuff like this totally undermines it.”

Undermining legitimate work in the sector also hurts LGBTQ2S+ people, but when information about scam conferences is not shared widely, activists are left vulnerable to the scammers, and public trust in the system’s ability to weed out bad actors is eroded. Part of the aim of fostering a global LGBTQ2S+ community is sharing helpful information across borders; protecting potentially vulnerable members from scams like these is an essential part of that kinship.

How scammers mask their identities

Fraud is an under-reported crime. When it is reported, laws in the countries where the scam artists operate or their victims are based dictate what happens next. A scam targeting LGBTQ2S+ rights activists in countries such as Ghana and Pakistan, where there is prejudice, is not likely to garner much sympathy from officials. Victims reporting such scams to the authorities are at great risk because it reveals that they identify as LGBTQ2S+ or that they do supportive work for that community, which may lead to more harm than the financial loss.

Even in countries where there is LGBTQ2S+ support, it is more effective to go after scam artists’ tools used to take money and data from victims and make it more difficult to carry out illegal activity. Tools used to promote and take payment for the Canadian conferences included Skrill, Facebook, GoDaddy, WordPress and MailChannels.

Searching the WHOIS information of a website’s domain can identify the owner and represents a check, but the fake CCF domain in this case used Domains by Proxy, which is a GoDaddy service that creates website anonymity. On the review website Trustpilot, multiple comments for Domains by Proxy allege the commenter encountered internet scams using the service.

Xtra emailed the address associated with the conference, asking to register and inquiring about how many people were signed up. We were told registration was closed and a follow-up email was not answered. Sending the email allowed us to see what information was available on the IP address.

The IP address from that email address and another Solomon Atsuvia was in contact with show that a MailChannels account was used to mask its true origin. The Vancouver-headquartered technology company is among many services that can be used to send mass emails and avoid “blacklisting,” an action that flags IP addresses or domains and diverts their email to spam folders.

A spokesperson for MailChannels said the company considers the activity being done with the emails to collect fake conference registrations against the company’s terms of service. “We’ll look into these specific addresses immediately,” they said in a statement.

Too close for comfort

Butt forwarded his email correspondence and invitation letter to a friend who works at the High Commission of Canada in Islamabad. “After 24 hours, he confirmed that no such organization existed in Canada and that there was no record of such a conference,” Butt says.

He then wrote an email to the organizers explaining that he’d confirmed the conference was fake. He did not hear back.

Atsuvia says he and his colleagues abruptly stopped their email exchanges with organizers and never heard from them again. The scammers would have already moved on to courting new victims.

Neither Atsuvia nor Butt knows of anyone who paid the fee to the scammers, but it’s likely some have lost money to the scam. It’s unknown how many people tried to register for the events’ sponsorships or how much money victims handed over to the scammers.

For whatever reason—embarrassment, a desire to put it behind them, an unwillingness to tell authorities of a connection to an LGBTQ2S+ conference—we will likely never hear all of their stories.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra