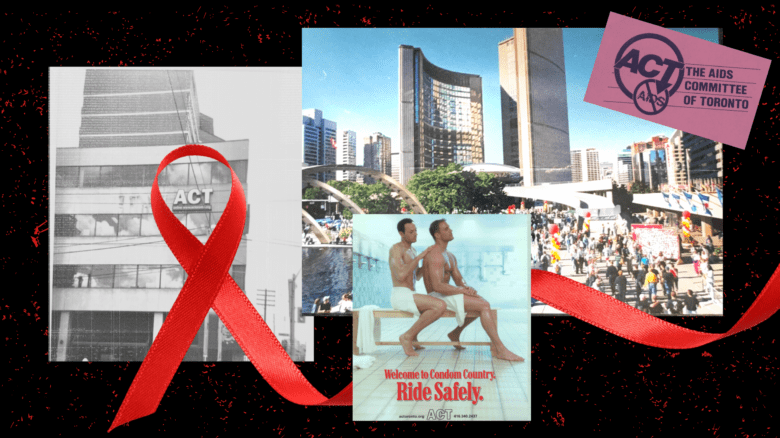

It was hot in the gallery of the House of Commons on June 23, 2005—the day that MPs voted to codify equal marriage into federal law. I was sitting there, elbow to elbow with fellow activists, many of whom had been fighting for LGBTQ2S+ rights for longer than I had been alive. We all shifted uncomfortably and rolled our eyes as we heard Conservative and some Liberal MPs make ridiculous claims about how allowing gay marriage would lead to the destruction of the nuclear family.

But when the issue came to a vote and we won, we stifled our hoots of joy, instructed by the stern security guards to remain quiet. As we filed into the lobby of Centre Block to celebrate, it felt like we could finally exhale. Codifying trans rights into federal law would come next, we said, and then we would all be protected. The dinosaurs will eventually die out and so will the discrimination against people like us, we said. There is no going backward after this, we said. How wrong we were.

I used to think I was privileged to come out as queer in 1999. My family was supportive and kind, having already accepted my younger brother when he came out as gay as a young teen. I was a university student in Montreal, where I could take classes in queer theory and spend my weekends at gay bars or lesbian parties with names like Meow Mix. As I explored my identity, more and more rights for LGBTQ2S+ people became recognized by the courts: the right to adopt children, to share health benefits, to inherit each others’ pensions and, eventually, to have our marriages officially recognized by law.

It took many more years and several failed private members’ bills before protections against discrimination due to gender identity and gender expression were codified in the Canadian Human Rights Act. I was sitting in the House of Commons gallery again in 2016 when that law was amended. I exhaled once more, but did not anticipate how life would soon become so much more dangerous for trans people, and how homophobic and transphobic vitriol would soon coalesce into an online mob targeting me and the people I love.

It’s 2022, and I have been out for 23 years. For the first time, only weeks ago, I was accused of being a “groomer.” In case you are not familiar with this particular term, it is meant to suggest that I am a child abuser. In the largely unregulated world of online discourse, it is a term being lobbed at queer teachers, parents of trans kids and folks like me—openly queer people running for city council, their local school board, or any other form of public office. It harkens back to the 1970s, when Anita Bryant launched a “Save Our Children” campaign in the U.S., aimed at outing gay teachers and removing their livelihoods.

“I didn’t anticipate the volume and the viciousness of the online harassment I would receive.”

When I decided to run for Ottawa city council to represent Somerset Ward a few months ago, I knew that I would be giving up a certain amount of privacy. I accepted that people would recognize me on the street and want to talk about bike lanes or snow-clearing. But I didn’t anticipate the volume and the viciousness of the online harassment I would receive. I have blocked thousands of troll accounts over the last few months and have had to start using a third-party app to manage my Twitter mentions. The last straw was just this week, when someone sent me an email asking how I would “prevent the dangers that the LGBT community is subjecting our children to.”

While many people seem to believe that the sustained backlash against the LGBTQ2S+ community (and particularly against trans children) is a uniquely U.S. phenomenon, it’s not. Many of us look on with disgust at the recent spate of attacks against drag queen reading events for children across North America. But this kind of hate has been festering in Canada for years now. Recall that three years ago, a group of anti-LGBTQ2S+ fundamentalists stormed a Drag Queen Story Hour in the Ottawa suburb of Bells Corners, shouting at the performers, scaring children and filming the attendees without their permission. Ottawa-based author and non-binary activist Amanda Jetté Knox regularly faces doxxing online, as well as direct threats against their wife and children. And just last week, former Ottawa mayoral candidate Alex Munter reported having homophobic slurs yelled at him while he went for a walk with his partner and son.

And now, there are currently several candidates running for positions on the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board with platforms seeking to remove queer and trans-positive lessons from the classroom. When the so-called “Freedom Convoy” occupation of Ottawa happened in February, at least one household displaying a rainbow flag found human feces on their front porch, and on Wellington Street, protestors displayed signs with vitriol about “gender ideology.”

I am obviously troubled by this rise in anti-queer hate. The good news is that every resident I have spoken to during weeks of knocking on doors is deeply committed to a city that is welcoming of people from all sexual orientations and gender identities. But I am seriously concerned about the impact of online radicalization, especially after so many of us have spent the last two and half years confined to our homes.

In June, when I attended the Federation of Canadian Municipalities’ annual conference in Regina, I heard over and over again how communities of all sizes were having trouble recruiting candidates from diverse backgrounds and that the potential for harassment was a huge reason why. Anti-vaccine trolls have formed an unholy alliance with anti-queer extremists, making it not uncommon for me to receive a Twitter comment simultaneously accusing me of killing children by promoting vaccination and suggesting that I am not credible because my bio clearly states my pronouns.

“Anti-vaccine trolls have formed an unholy alliance with anti-queer extremists.”

A lot of people have asked me why on earth I would step forward to run for public office in the midst of this nasty political climate. And it’s true that since the convoy occupied Ottawa and an army of trolls descended on my Twitter mentions, I have tightened up my online and personal security. But at the end of the day, I don’t believe that we should let the bullies win.

The campaign I am running for city council is not explicitly about fighting homophobia and transphobia, it is more about reviving our downtown core, investing in social services and promoting active transportation. But the reality is that queer and trans folks are deeply impacted by city politics. For example, between 25 percent and 40 percent of homeless youth in Canada are LGBTQ2S+. Fighting to maintain and expand services that help queer and trans youth access housing and mental health support is key to solving homelessness in any Canadian city.

And when it comes to school board elections, the need for queer and trans school trustees couldn’t be greater. The decisions that trustees make impact whether or not a non-binary kid will have a place to go to the bathroom, or whether or not children will learn about families like mine in the classroom.

No matter where you live, do your research when it comes to voting for city council and school board representatives, and make sure that you are not elevating people with hateful views to positions of power. Municipal and school board elections typically have the lowest voting rates of any level of government in Canada. By knocking on thousands of doors in my neighbourhood, I hope to help change this.

I often think of a protest sign that became popular after Donald Trump was elected in the U.S. that stated: “I can’t believe we still have to protest this shit.” But I refuse to even imagine a world where my daughter could lose the rights that my generation fought so hard to gain.

This is why we march in Pride. And this is why I am running for office—trolls be damned.

Ottawa’s Capital Pride Parade is August 28; the city’s municipal election is October 24.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra