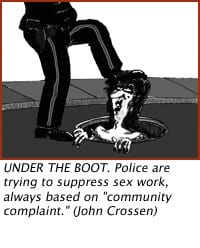

Representatives from the queer community are telling police to leave sex workers alone, but the police aren’t listening.

Sex workers — gay, trans and straight — were on Michele Penney’s mind at the Ottawa Police Services’ annual OUTreach conference on queer issues, in the wake of more measures designed to push the sex trade underground.

Penney is an outreach worker at Minwaashin Lodge. She assists homeless aboriginal women, some of whom are sex workers. She also helps transgendered sex workers, and, in her experience, their interaction with police is “not positive.”

Police can make the lives of sex workers difficult, but queer sex workers have a harder time than most, she says.

It’s doubly infuriating because Ottawa police claim that when they conduct street sweeps or send john letters, it’s in response to “community complaints.” But the police don’t appear to be listening to complaints from the queer community — complaints that boil down to “stop harassing street workers.”

Murdock MacLeod of the Ottawa Police Service says officers treat all sex workers the same regardless of orientation.

“We don’t keep statistics on male prostitutes but there is no question that we have them,” says MacLeod.

But that may be missing the point. The laws that subject hookers to criminal offences are the same ones used to raid bathhouses, most recently in Hamilton (2004) and Calgary (2002.) Gays have always argued for sexual self-determination — a position supported by queer groups like the Coalition for Lesbian and Gay Rights in Ontario, the Sex Laws Committee and the Committee to Abolish the 19th Century.

In the meantime, Ottawa is entering year two of its crackdown on street workers.

“Everybody fears the uniform regardless of who you are,” MacLeod says. “The people who work the street know the officers. Some [officer-sex worker relationships] are good and some are bad.”

Penney says those relationships often depend on the age of the officers involved.

“The younger generation of officers has had the upbringing of tolerance and understanding; some others are cemented in their ideas,” she says.

Penney and her colleagues sometimes visit police stations to ascertain the age of officers on duty before encouraging their clients to lodge complaints. But she also says her clients “do not have a good trust level with workers trying to help.”

“We need to get rid of that [distrust] as much as homophobia,” she says.

One way Penney and her colleagues work against that distrust is by accompanying clients to police stations, providing a trusted “third person” to whom they can tell their stories if they are uncomfortable talking to officers.

Meanwhile, Penney fears that measures designed to push the sex trade underground make workers invisible and endanger their safety.

“We have to deal with that,” MacLeod says. “But the community complains about the visible sex trade.”

Jeff Leaper heads the Hintonburg Community Association. That group is one of the loudest voices of complaint.

Hintonburg is the centre of the city’s controversial “community safety letter” program, often called the “Dear John” program.

MacLeod, the program’s founder, explains.

“If we catch an individual with a prostitute, we send a letter,” he says.

Leaper says 36 letters have been sent to known johns since early March, and sex trade activity is “much less prevalent than it has been.”

Penney calls the letter program a “crock of crap.”

“How do they know who is driving the car?” she says. “I could be doing legitimate business in the area, and what if I’m married?”

But Ottawa police are eager to defend the program.

“Our intent is not to be marriage wreckers, just to educate johns,” says MacLeod, adding that letters are sent by courier to known johns who have been approached by police. The letters are sent “not to the registered owner but the person driving the car,” he explains. “The person is positively identified.”

A pamphlet produced by the Hintonburg Community Association is full of lurid examples of community complaints. Leaper reports “women screaming at the top of their lungs fighting at a school bus stop” and a small child telling his mother, “Mom, there’s a naked woman in the backyard.”

He reiterated those views at a panel discussion on prostitution reform organized by the Canadian Civil Liberties Association for the national capital region in June. There, he said that the sex workers who live and work in Hintonburg are “not part of the community.”

Now that the police have heard from both the Hintonburg Community Association and the queer community, the question is: whose community are they listening to?

Todd Klinck, a gay man and former sex worker who now manages Goodhandy’s, a sex club in Toronto, rejects these perceptions.

“Since I clearly do not see prostitution as something that is bad, unhealthy or harmful, obviously I don’t think it causes harm to the community,” Klinck says. “The fact that people do not recognize that consenting adults are capable of having healthy relationships on an escort-client level is a big problem.”

Klinck and Penney both support removing the sections of the Criminal Code that address prostitution. Klinck believes sex workers should be allowed “to operate like any other freelance consultant.”

Klinck says he did not have much interaction with the police while working the streets of Toronto in the 1990s, but for Penney’s clients, the story is much different.

“They are ostracized, targeted and singled out,” Penney says, “and not taken seriously because they are working on the street.”

Penney encourages the police to “keep on doing outreach events and inviting the public” as well as becoming more involved in sex worker’s communities.

None of Penney’s clients agreed to be interviewed for this article.

“They’re targeted enough,” she says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra