Théo Wouters looked exhausted and heartbroken as he began to digest the news of the judge’s ruling on Nov 26.

“I can’t believe this,” he told me. “This is a terrible day for all minorities in Quebec.”

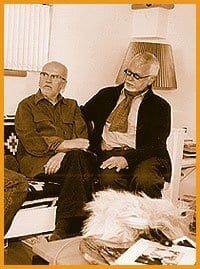

Wouters, a resident of the Montreal suburb Pointe Claire, had just heard that his neighbour Robert Walker had been acquitted of all four counts of harassment and assault. Wouters and his lover of almost a quarter century, Roger Thibault, had made loud claims over a two-and-a-half-year period that Walker was a vicious homophobe who’d made victims of them.

Walker and his wife Norah had lived harmoniously beside Wouters and Thibault for more than a decade. Then suddenly, the neighbours’ relationship began to deteriorate, spiralling downward in a very nasty manner.

The case came to light via Wouters and Thibault, who made their case to the media that they were being subject to harassment because they are gay. Neighbours from two different households, they claimed, were attacking them verbally, with one neighbour even trying to run them down with a car.

Understandably, gay activists and the media were immediately drawn to the story. On first glance, it appeared to be the clear-cut case of a relatively defenceless, sweet and elderly couple being mistreated simply because they were gay. Operating under the usual journalistic principles of balance, Montreal media types were at something of a disadvantage, in large part because the Walkers simply refused comment.

Left to the spin of Thibault and Wouters, who soon came to be referred to as Roger and Théo by the local press, the case snowballed into a national story. In the summer of 2001, more than 4,000 people marched through the streets of Pointe Claire in solidarity with them, concerned for their safety in the conservative suburb.

When the Walkers finally did break their silence last spring, I, along with a number of other Montreal journalists, found ourselves feeling rather odd. Both told stories which painted a very different picture of things. Thibault and Wouters, according to the Walkers, had been model neighbours, and then, abruptly changed, virtually overnight, starting to complain about things that seemed trivial and nonsensical: a compost heap out of place, flower boxes that didn’t sit quite right, the sound of a dog barking. There were incessant phone calls to the police, resulting finally in a restraining order against Walker.

When the Walkers finally broke their silence, they chose to speak with me, in part because I’d written about the case, also in part because I am a gay reporter myself. They told me long stories of how Wouters and Thibault had taunted Norah Walker as she arrived home from hospital after enduring another bout of chemotherapy. “You’re not that sick!” they would reportedly yell. Amazingly, when I asked Wouters about this story later, he didn’t deny it.

What was once a clear-cut case of homophobia now seemed far murkier. Both couples were claiming they were the real victims of harassment. After my new accounting of the affair ran, gay activists immediately began to distance themselves from Wouters and Thibault.

Two things had already happened, though. Parti Québécois activists had already earmarked Wouters and Thibault to have a spot in history. They would be the first same-sex couple to legally unite under Quebec’s new civil unions law. Their bond was drawing international attention, including a segment on the PBS series In The Life. (Appearing to sense a growing doubt about Wouters and Thibault’s version of events, the program sidestepped any mention of the harassment charges against their neighbours.)

Second, the criminal trial began to unfold. And many of the community’s worst suspicions became confirmed. Wouters contradicted himself repeatedly on the stand, getting stories wrong, mixing up facts and admitting to paranoia. The Montreal Gazette’s Sue Montgomery attended the trial every day in November.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she says now. “They really looked ridiculous.” Among the evidence they presented was a photo of a golf ball, one Walker had allegedly lobbed at them as they sat outside.

Now that the criminal case is over, Wouters and Thibault say they will push ahead. Though they’ve opted against a civil trial, a Quebec Human Rights Commission Tribunal is slated for April.

Their effect upon the evolution of gay rights in Quebec, the most progressive territory for gay men and lesbians in North America, is impossible to tell. But as it stands, public perception is that two of the most famous gay activists in the province could be anything from overzealous in their pursuit of persecution to simply out of their minds.

* Matthew Hays is an associate editor at the Montreal Mirror.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra