Credit: Sergei Bachlakov

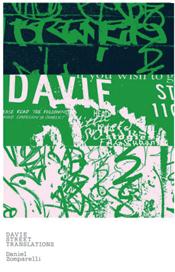

Daniel Zomparelli’s debut book of poetry, Davie Street Translations, was inspired by you.

You, high on drugs and admiring glances from cute boys, dancing at a club to a DJ who plays nothing but Lady Gaga.

You at Hamburger Mary’s at 2am eating your feelings.

You walking the streets, lonelier than the homeless guy sitting on the sidewalk.

You in the presence of a drag queen who’s such a star, each step she takes is trailed by a spotlight. Even if the spotlight is only in her mind.

You on Grindr, needing to be loved.

And you at the PumpJack Pub, looking at your future in all of its saggy-scrotum and leather-chaps glory.

When I meet Zomparelli over coffee, the first question I pose is, “What is it about Davie Village you find inspiring?” As soon as I ask, I feel dumb — hadn’t I read his book? You know, the one filled with a hundred pages of what he finds inspiring about the Village. I am about to start over when I notice him struggling for an answer.

“You only wrote an entire book about it!” I laugh, until he says it isn’t necessarily Davie St he finds inspiring but the culture it represents, for better and worse.

“The people who inhabit the Village are inspiring, and the amount of people it brings together is inspiring,” he says.

“I just question a lot of its culture,” he continues. “A lot of what I find inspiring is what I find wrong, complicated or confusing about gay culture, which is enforced in the Village.”

“A lot of the culture is about how you look and who you’re friends with, so it replicates a lot of the problems of high school, with popularity and cliques,” he explains.

The lives depicted in his poems are all connected by one main thread: yearning. A yearning to find their place in the world and fit in — and the sacrifices and self-destructive choices they make when they feel they don’t.

“We have to deal with so much growing up,” Zomparelli says. “We spend so much time beating ourselves up, or letting other people beat us up, that letting go and opening up takes longer than it would for someone who didn’t have those experiences.”

In his poems about drugs (he writes about them all, including the holy trinity: MDMA, cocaine and Special K), he conveys how when we get beat up, or beat ourselves up, we start searching for a way to flee the bruises. “We all use coping mechanisms for our insecurities,” he says. “There are healthy ways to deal with them and unhealthy ways. Usually, the unhealthy ways are the fastest and easiest to approach.”

Despite their potentially dark side, Zomparelli still believes in the importance of gay villages. “Usually you don’t have a lot of gay friends when you’re first coming out because you’ve been closeted,” he says. Having a space to go, “knowing that there will be other gays there, makes it easier.”

“That being said . . . I find a lot of people stepping into the Village and then stepping out once they’ve found their groundings. I think as we become more mainstream we diversify, so you don’t necessarily have to fit into the culture of Davie St if you don’t want to.”

Davie Street Translations is an attempt to capture a moment in gay Vancouver’s time. Each poem is a snapshot, Zomparelli says. Or a love sonnet. Among his poems are odes to the drag queens Isolde N Barron, Jaylene Tyme, Vera Way and Raye Sunshine.

“They all said they liked them; I don’t know if that’s them being nice or not. I think they really like that it was immortalizing their characters,” Zomparelli says. “That was the whole point of taking the Shakespearean sonnets — where he immortalizes his loves and immortalizes the beauty and youthfulness of it — and then replicating it for drag queens.

“To be honest,” he confides, “I’m not the craziest fan of drag queen performances, unless it’s done really well, so the queens I chose do it well. It’s their personalities when you talk to them in their drag queen persona. They’re captivating and they own attention. It’s kind of wonderful to be in their presence.”

My favourite poem in Translations is called “PumpJack” and is about growing older. It’s written as a conversation between two friends, with lines like,

I think we’ll just get more kinky

Yeah, like, first a slap, then a pinch, then butt plug

Won’t we just be antiquing by then?

The poem stands out to me because it’s about two people embracing their fate instead of holding on to their past, as so many of us do, even when our past is painful.

The poem captures the liberation of aging, the same liberty that Zomparelli feels the PumpJack Pub evokes. “Whenever I go there I don’t feel the pressure to be anything specific,” he says. “You don’t need to be on all the time or flirty. Going to 1181 or those bars, there’s a pressure we put on each other to be really fun, have nice clothes, be working out all the time, have a great body, the right haircut . . . It’s just too much pressure. Whereas the PumpJack, everyone’s really nice, someone’s hand is on your butt at all times, saying you look cute, no matter what you’re wearing.”

While illustrating the anxiety we inflict on ourselves and each other, our desperation to be loved and our escapism when we don’t feel good enough to be loved, Davie Street Translations also offers a glimmer of hope: we are at our best when we accept who we are and who we are going to become.

Which, if we’re lucky, will be buttplug-wearing antiquers, one hand holding a beer, the other on the backside of a young boy who needs to be reminded that not only is he cute, but that he’s going to be all right.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra