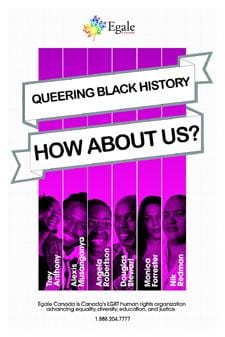

AWARD WINNER. Trey Anthony is one of six recepients of the first Queering Black History awards. Anthony is the creator of the television show Da Kink in My Hair. Credit: egale.ca

To mark Black History Month, Egale Canada and Stop Murder Music Canada (SMMC) have named six recipients of its first Queering Black History awards.

The winners, selected from nominations submitted to Egale, will be featured on a postcard and poster that will be distributed to universities, school boards and queer community centres across Canada.

“With any racialized group within the queer community the voices or names of people can be left off,” says Akim Larcher, the founder of SMMC. “Within the wider black, African or Caribbean communities queer names and people tend to be a bit invisible during Black History Month.

“There tends to be no discussion of sexual orientation or gender identity.”

The winners include Trey Anthony, the playwright of Da Kink in My Hair and creator of the television series of the same name.

Also named was Alexis Musanganya, the Montreal-based founder of Arc en ciel d’Afrique, a community organization for queer immigrants of African and Caribbean origin, facilitator of Gris Montreal, which seeks to educate students and recent immigrants about homosexuality, and copresident of Multimundo, which tries to build coalitions among queer groups in various cultural communities.

Angela Robertson, the executive director of Sistering, an organization aiding poor and homeless women, was a winner. Robertson is also currently a board member of both Central Neighbourhood House and Second Harvest and the chair of the Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention (Black CAP).

Equity consultant Douglas Stewart was a founding member in 1983 of Zami, the first black and West Indian queer support group in Toronto. He also helped found the Black Lesbian and Gay Action Group, Aya Men — a group for black gay men — and the Blockorama venue at Pride. Stewart was also the founding executive director of Black CAP.

Monica Forrester has worked with the 519 Community Centre for 10 years on programs for sex workers and on guiding trans women to social agencies. She has also been an educator on trans issues at the Fred Victor Centre and produced the bimonthly zine Trans Pride Toronto.

Nik Redman is a member of the GBQ Trans Men’s Working Group, the Ontario Gay Men’s Sexual Health Alliance, Toronto’s Prisoners Justice Action Committee, the Trans Fathers 2B Parenting Course Project Team and the MaBwana Community Advisory Committee, He is also an online facilitator for Ontario’s HIV Stigma campaign for HIV-positive gay men.

Robertson says she’s honoured to be named and hopes the awards will help make black homosexuality more visible.

“It serves as an affirmation both of the individual and as an historical marker for those who will be coming behind, particularly young people, those who will be coming out in places where there are no critical masses of people who look like them,” she says.

Robertson says there is a long, unacknowledged history of queer black activism.

“Black queer activism has had a very long tradition,” she says. “That history has not always been clearly visible outside the queer community. We need to bring that history beyond the queer community. Black and African queer leaders have also been leaders within black communities. There have been a number of black queer women who have been leaders in the fight against violence against women.”

Robertson says there has also been a lack of acknowledgement within queer communities.

“I think we have had struggles to be recognized within queer communities,” she says. “This is also a recognition of our contribution as racialized people within queer communities.”

Redman agrees that queer people of colour often get lost.

“There’s racism still in the queer community and obviously homophobia and transphobia in the black community,” he says. “Queer voices and trans voices are basically invisible a lot of the time in the black community. Black people and people of colour are often not visible in the LGBTQ community. It’s not even visibility, often there’s a failure to acknowledge that we even exist there.”

But Redman says the awards are also about the work done by individuals.

“It’s about visibility but it’s also about acknowledging members of our communities and what they’ve accomplished.”

Larcher says the program will continue in future years and he hopes winners will expand beyond the Toronto area. Except for Musanganya, all of this year’s winners are from Toronto.

“I think it’s reflective of the community itself by virtue of the activism and achievement that’s taken place,” says Larcher. “We don’t want to only choose people from Ontario but that’s where the concentration is at the moment.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra