On Mar 17, St Patrick’s Day in 1992 I met with a group of friends at my home to solicit their thoughts and opinions about running for Edmonton’s City Council that fall.

By April, the Edmonton media was reporting that “Michael Phair, a gay activist, announced he would seek election in Ward Four to city council as the first openly gay councillor.”

That October, among 14 candidates running in the ward, I topped the polls and became Edmonton’s first openly gay councillor. It was exhilarating for me and, I think, for Edmonton’s lesbian and gay community. When I look back, I realize, that despite conventional wisdom, it was much easier to be out before becoming a politician, rather than face the possibility of being outed while in office.

I had moved to Edmonton in 1980 and became publicly active in a number of gay, lesbian and AIDS organizations. When Jan Reimer was elected mayor in 1989, she urged me to run for city council in the next election. My initial reaction was that I was sure that an openly-gay person could not win, especially in Alberta. I was too public to try to go back in the closet, nor did I want to go back in.

Truthfully, the prospect of running as a gay man was frightening – I was afraid of the kind of comments or worse that I might face. Though there were many lesbians and gay men living in my chosen ward, there weren’t enough to win an election. I worried that I might well lose and knew that would affect me personally and could affect perceptions of the gay and lesbian community.

On the other hand, the only other person that I knew who was out and then ran for office in Canada was Glen Murray in Winnipeg, and he had been successful.

Murray Billett, who had run Glen Murray’s first campaign in Winnipeg, agreed to chair my 1992 campaign team. He was well aware of the task of winning an election for an openly gay candidate.

“The campaign team did spend time discussing and planning the homo factor,” Billett recalls. “Running for political office in the late ’80s and ’90s had distinct disadvantages. Homophobia was a larger factor at that time. It had a definite chilling effect to the dynamics of the campaign if we allowed that to happen. There were even issues of safety to consider, being very out, very public, leaves one open for reprisal. While we didn’t dwell on it, I know those of us close to the core of the campaign knew the reality.”

My successful re-election campaign in 1995 was personally more difficult for a number of reasons, including that this time thousands recognized me as a gay man – what people might not have absorbed from my first campaign, they absorbed from my activities as a councillor. I realized the possibility of losing power for being gay.

While the landscape of public attitudes has gradually shifted positively, there are also new drawbacks. Billett, who organized my 2001 campaign, says, “the gay candidate running today can no longer count on the orientation based ballot cast in his or her favour. I believe that running today is done more on merit than on orientation.”

So there are more pressures to face in coming out once in office, from the media and from the public and from a politician’s desire to keep the focus on merit, not orientation.

In the end, I stand my decision to be out before running for public office, to avoid tougher decisions later on.

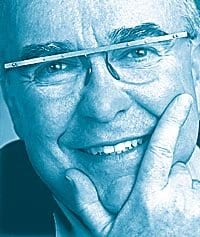

* Michael Phair has represented his Edmonton riding on city council since 1992.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra