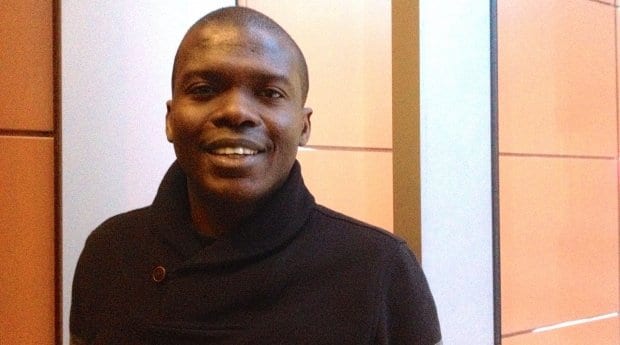

The Quebec Superior Court accepted a black, gay graduate student’s claim for judicial review on Friday, Jan 9, after he decided to appeal a decision by the Human Rights and Youth Rights Commission of Quebec that concluded he was not discriminated against for his sexual orientation.

Kofi Norsah, who is writing his thesis within the School of Social Work at McGill University, was dismissed from a field placement in 2011 after he objected when his supervisor told him to hide his sexual orientation.

“It’s a victory for Mr Norsah,” said Melissa Arango, Norsah’s lawyer. “He didn’t get a chance to be heard.”

The Human Rights Commission filed a motion to dismiss the request for judicial review; the motion was rejected by the judge. Although Norsah’s case will be heard at the Superior Court, he will not have the chance to receive the $15,000 in compensation he originally asked for, according to the judge’s ruling. While the court cannot change the commission’s decision about whether discrimination occurred, it does have the power to order it to redo the investigation.

Norsah claims that after meeting with a representative from the School of Social Work, he received no support and within days was dismissed from his placement at Saint Columba House, a community centre affiliated with the United Church and situated in a low-income Montreal neighbourhood. The internship was a prerequisite to entering the graduate program.

Norsah asked his supervisors for advice after a woman from the community centre asked him whether he had a girlfriend. His supervisor allegedly told him to keep his sexuality a secret, because the client, who has a history of domestic violence, was “afraid of gay men.”

“If you Google my name, you can find out that I’m gay, because I’m engaged in those community programs,” Norsah told his supervisor. “I’m not visibly gay, so you can tell me not to be open,” but this approach doesn’t work for LGBT social workers that are more open about their sexuality, he said.

He then filed a demand for compensation with the Human Rights Commission, which originally rejected his case on the grounds that “sexual orientation is a private matter,” siding with Saint Columba House’s position that it shouldn’t be mentioned to a client.

“What policy and what legal analysis does that come from?” asks Fo Niemi, co-founder of the Center for Research-Action on Race Relations (CRARR), a non-profit civil rights organization. CRARR is representing Norsah, who is also a native of Ghana.

The Canadian Association of Social Workers told The McGill Daily that it “does not have a formal position defined on this subject.” In 1977, Quebec was the first province in Canada to include a sexual orientation clause in its Human Rights Code.

Norsah appealed the initial rejection on the grounds that his sexual behaviour was private, but his orientation and gender identity were not. His case was eventually accepted and investigated. If the commission had found his complaint valid, Norsah could have received financial compensation and it would have set a precedent that might prevent the situation from happening in the future.

“I have the right to get married in Quebec, but I can’t talk about my family at work with a client because if I talk about my family, I will reveal my sexual orientation.”

Three years later, in April 2014, the commission presented a draft of the factual report to Norsah for review. The first sentence of the report states that Norsah is black, then goes on to use language that suggests Norsah’s sexuality is a lifestyle or choice. The draft report also says incorrectly that Norsah is from Guinea.

“When we saw the decision, we realized the commission just didn’t get it,” said Niemi.

Norsah’s lawyer, Arango, will fight to get the commission to review his case based on intersectionality, which considers multiple identities as being inseparable.

Norsah says the commission’s investigator ignored evidence he submitted of recorded conversations with supervisors and refused to meet with him to discuss the incident.

CRARR presented a multipage commentary on the original draft, but in October the commission concluded that Norsah’s case was not discrimination.

Norsah says he is afraid the investigation’s conclusion will be used to continue to discriminate against minorities on the basis of client privilege.

No date has yet been set for when the court will review the case.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra