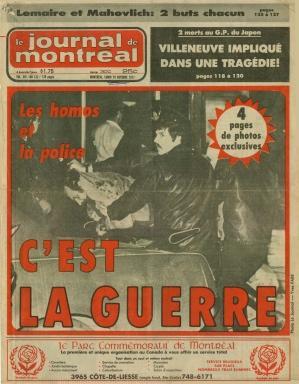

WAR. Front page of the Journal de Montreal following the 1977 police raid on the Truxx gay leatherbar on downtown Stanley St. Credit: image courtesy of Quebec Gay Archives

Imagine a cool breeze running through your hair as you’re having hot sex with your lover in a grassy field far from home. Then imagine being caught by the local authorities and sentenced to death.

It happened in Montreal in 1648, when the city was but a tiny outpost of the French empire, surrounded by valleys and fields as far as the eye could see. A gay military drummer with the French garrison stationed to protect the Sulpician Order of priests — the seigneurs of Montreal — was charged by the order with committing “the worst of crimes” and sentenced to certain death in the galleys.

“The drummer’s life was spared after Jesuits in Quebec City intervened on his behalf and he was given a choice by the Roman Catholic Bishop of Quebec: die or become the colony’s [first] executioner,” explains Ross Higgins of the Quebec Gay Archives.

The unidentified drummer took the executioner job.

I bet gays and lesbians everywhere know how that drummer must have felt. As I was researching the history of gay life in Montreal, I was impelled to uncover the parallels between contemporary queer lives and those of our siblings over three centuries ago.

Because, as many historians contend that gays and lesbians don’t have common goals and ideas or shared languages and experiences — in effect, no culture to call our own — we must remember that our lives are more than just a spotty chronology of dingy nightclubs, police raids and gay Pride parades. How those elements combined to shape the queer experience is what makes up our history.

GYPSIES, TRAMPS AND THIEVES

Before the young French officer Paul de Chomedy de Maisonneuve founded Montreal in 1642, it’s worthy to note the cyclical intolerance of minorities like Jews, homosexuals and Gypsies in Christian Europe.

“It seems to have been fatally easy throughout most of Western history to explain catastrophe as the result of the evil machinations of some group distinct from the majority,” the late historian John Boswell wrote in his landmark book Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality (University of Chicago Press). “And even when no specific connection could be suggested, angry or anxious peoples have repeatedly vented their negative emotions on the odd, the idiosyncratic and the statistically deviant.”

So it was in Montreal, where fewer than a thousand settlers endured grueling winters and disease for decades, and where guards stood on duty against Indians to protect workers tilling the fields outside their walled town.

During this period, military records show that a decade before the French signed a multilateral peace treaty with 38 North American native tribes at the inaugural Meeting of First Nations in Montreal in 1701, two soldiers and their lieutenant, Nicholas Daussy de St-Michel — likely caught having a threesome — were thrown into a bailiff’s prison and charged with sodomy. The soldiers were each sentenced to prison while Daussy was fined, ordered to pay all court costs and banished from New France.

“Considering the prescribed punishment [in Montreal at the time] was burning at the stake,” Higgins points out, “these sentences were relatively lenient.”

Though few records documenting gay and lesbian life anywhere in North America over the next 150 years have survived, historians agree queer life managed to thrive in gateway cities like Montreal and New York. For instance, newspaper clippings from this period clearly indicate Old Montreal’s military Champs de Mars (today located directly behind Montreal City Hall) was a popular cruising ground for gay men.

Just because queers were closeted, though, didn’t mean they didn’t have their own social circles. In fact, one of the ridiculous myths I believed as a young teen was that gays and lesbians led solitary lives, with no contact with each other outside their homes — and certainly had no nightlife — before the rise of the gay liberation movement.

The first recorded gay establishment in North America — and the namesake of this column — was Montrealer Moise Tellier’s “apples and cake shop” on Craig Street (now St-Antoine) in Old Montreal in 1869, where men met and had sex. But back then anyone outside of the loop had to be extremely careful about where they got laid. For instance, Montreal police records from the summer of 1891 document the arrests of William Robinson and William Looney for having sex by the fort on Ile-Ste-Helene.

“William Robinson was on his back with his pants down his legs and his shirt lifted above his chest,” the arresting officer wrote in his deposition. “Looney also had his pants pulled down and shirt pushed up and was lying on top of Robinson. Their private parts were touching and they were making up-and-down movements. They continued to do this for 10 minutes.”

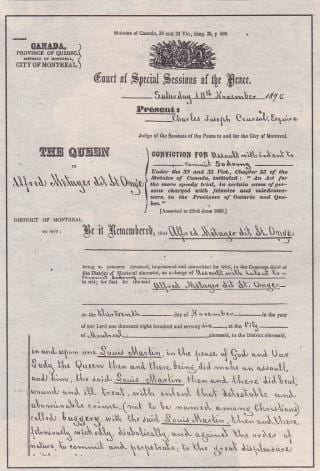

Alfred Metayer’s November 1876 conviction for assault with intent to commit sodomy is equally disheartening. Municipal-court judge Charles Jospeh Coursol sent Metayer to St-Vincent-de-Paul Penitentiary for three years for “that detestable and abominable crime (not to be named among Christians) called buggery, with the said Louis Martin, then and there feloniously, wickedly, diabolically and against the order of nature to commit and perpetrate, to the great displeasure of Almighty God, [and] to the great damage of the said Louis Martin.”

The fact that all gays and lesbians did not internalize the dominant culture’s view of them as sick, perverted and immoral went a long way to helping establish an exciting singles-bar scene in Montreal that, unlike the straight world, dominates queer life well beyond middle-age.

That went over especially well when Montreal was a major entertainment capital, second to only New York and ahead of Chicago on the vaudeville circuit, and the city was still wide open to gambling, boozing and whoring during American prohibition. Even Al Capone opened a nightclub here (it still stands today as the Lion d’Or).

The city’s unofficial theme song was Irving Berlin’s 1928 Prohibition-era hit Hello Montreal! and the festivities were presided over by “Mister Montreal,” the city’s beloved seven-time mayor Camillien Houde.

Like they sang in Hello Montreal!, “I’ll make whoop-whoop whoopee night and day!”

Later, when Canadian military recruits returned home from World War II knowing they weren’t the only fags and dykes out in the world, dozens of gay bars opened up downtown, notably the Down Beat at 1422 Peel and the debut of legendary female impersonator Armand Monroe — better known then as loudmouth Marilyn Monroe impersonator “La Monroe” — in that bar’s Tropical Room in 1957.

In fact, men were first allowed to dance together in Montreal on the night of Aug 27, 1958, to mark Armand’s birthday. “When I began managing the bar,” Armand told me once, “I introduced a new policy: gay customers served by gay waiters and gay bartenders!”

Meanwhile, Denise Cassidy, better known by her nickname Babyface — inherited from her brief stint as a professional wrestler — began her career in the bar business in the 1960s as a busgirl at the Ponts de Paris on St-André Street, then went on to manage six of Montreal’s first lesbian bars from 1968 to 1983.

“The girls were scared to come,” Cassidy told Hour magazine in 1996. “They weren’t out like they are today and they were afraid their families would discover what kind of bars they went to.

“The first bars were pretty tough — it was a hard milieu, especially when men discovered my bars were for women only. There were always men who wanted to come in. I worked with a baseball bat by my side for the longest time. And there were fights! Friday night was hell sometimes!”

“There were hurdles back then but we were all in this together,” explains Henri Labelle, who first went to a gay bar when he was 17 while working as an interpreter at Expo 67.

Like Cassidy, Labelle also worked as a waiter before becoming a gay-nightclub manager in the 1970s (he’s now a lecturer at Concordia University). “We had to work against the establishment for our own preservation. Once you were in the milieu and broke through the barriers, though, people were friendly and trusting.”

THE BOYS IN BLUE

Those who thought queer watering holes would shelter gays and lesbians from homophobia were mistaken. Some of the bars may have been owned and run by gays and lesbians, but at the end of the day when the boys in blue dropped in, we were still a bunch of queers.

In the 1960s, after Jean Drapeau was elected mayor of Montreal, vice squads raided gay clubs to fill up their quotas.

“It was too much paperwork if they booked everybody,” explains Ross Higgins.

When the 1970s rolled around, though, the cops arrested everybody. They burst in with machine guns and cameras. They threatened to call employers of the men and women they arrested and publish their names in Montreal’s daily newspapers. And they always, always snapped pictures.

When officers raided the Neptune bathhouse in Old Montreal in 1976 (today it stands as the huge 456 Sauna), Labelle — who was working as the cashier that night — says, “[The police] yanked off people’s towels and threw everybody together and took pictures and charged them all with being in a common bawdy house. There was a former mayor’s son there, a government minister, a secretary to the Catholic Archbishop and a couple of cops, but they were ushered out the back door while everyone else was thrown in paddy wagons.”

Labelle also wonders who really firebombed the Aquarius bathhouse on Crescent Street in April 1975, when the Gay Village was still downtown before the exodus east after the 1976 Montreal summer Olympic games.

Three customers died in the Aquarius fire, and two of them — found burnt to a crisp by the second-floor fire exit — were buried in paupers’ graves because their corpses were never identified or claimed by their families.

Over 30 years later, Labelle and I visited the overgrown graves of those two gay men in Paupers’ Field in Montreal’s Notre-Dame-des-Nieges cemetery atop Mount Royal and, I tell you, I couldn’t help but tear up.

Today, when I attend gay Pride parades, I think of these victims and count my blessings. I’m saddened so many lives were uselessly destroyed, and more spirits broken. I’m also maddened we felt powerless to do anything about it for so long.

For centuries, the Catholic Church, politicians and the Montreal police defined what it meant to be gay in Montreal, and they’ve never apologized for any of it.

Now that gay people are redefining our lives and reclaiming our history, I almost want to thank the cops and their systematic oppression for inadvertently mobilizing a gay liberation movement — but then I remember that we should have been able to come out several generations earlier.

Moise’s Apples is Richard Burnett’s monthly Xtra.ca column on the history of gay Montreal. Burnett is also Editor-at-Large of Montreal’s Hour magazine where he writes his national queer-issues column Three Dollar Bill.

Burnett’s column title — Moise’s Apples — is a reference to the first recorded gay establishment in North America. In 1869 in Old Montreal, men met to have sex at Moise Tellier’s “apples and cake shop.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra