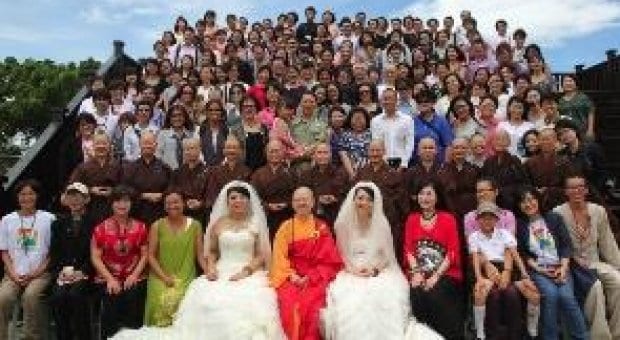

Credit: Taiwan LGBT Family Rights Advocacy

Two 30-year-old women from Taipei married Aug 11 in Taiwan’s first gay Buddhist wedding ceremony.

Huang Meiyu and You Yating exchanged prayer beads in front of about 250 guests at the Hongshi Buddhist Seminary in the lush farmland outside Taipei. Guests included Buddhist classmates, journalists, monks, and gays and lesbians from across Taiwan.

Before this year, neither Huang nor You had given much thought to marriage. “We didn’t think we needed it to legitimize our relationship,” Huang tells Xtra.

But this winter, as Huang watched an English television program about gay marriage, she thought, “Marriage is more than just a piece of paper. It’s something a whole family shares in.” When her girlfriend of seven years, You, came home from work, Huang proposed.

You had also been watching television. In the movie If These Walls Could Talk 2, she saw a lesbian unable to stay with her dying partner because they were in the closet. “What if that happened to us?” she thought. So when Huang proposed, she said yes.

Gay marriage still has no legal status in Taiwan. Challenges to the law are slowly making their way through the courts, but progress has been slow. Wu Shaowen, the head of the Taiwan LGBT Family Rights Advocacy, says Taiwan’s large and interconnected families put pressure on gays and lesbians. It’s hard to come out of the closet in a small, traditional country where family is always close at hand.

Beyond the challenge of being gay in Taiwan, Huang and You are also Buddhists. They attend Hongshi Buddhist Seminary together, and Huang works as an addiction counsellor with a Buddhist non-governmental organization (NGO). For their wedding to be meaningful, they decided it would have to be Buddhist.

They spoke to their friends at Hongshi, and even to monks, but nobody was sure if gay weddings were allowed under Buddhist rules. For a real answer, they were told, they would have to speak to the head Buddhist teacher at Hongshi, Zhao Hui.

Buddhism’s relationship to homosexuality is even less defined than that of Christianity. Ancient texts make little mention of homosexuality, as such, leaving everything open to interpretation.

Some Buddhists ban gay sex based on a precept against “inappropriate sexual behaviour.” Others ban gay people from becoming monks. Some Buddhist traditions in Japan, China and Mongolia, on the other hand, have historically celebrated homosexuality and even encouraged it.

There are now as many traditions and opinions on sexuality as there are branches of Buddhism. The Dalai Lama, the head of one Tibetan sect of Buddhism, has rather apologetically stated that, while there is nothing wrong with homosexuality from a secular perspective, Buddhist scripture warns against it for believers. But progressive Chinese Buddhist teacher Xing Yun endorses homosexuality provided that, like all pleasures, it is enjoyed in moderation.

Bhikkhuni Shi, a Buddhist teacher at the Yuan Rong Buddhist temple in Vancouver, says that although she has no prejudice or ill will toward gay people, it would be unlikely that a gay wedding could take place in her temple. Most Taiwanese Buddhists, she says, are simply too traditional and unaware of gay culture to accept a gay wedding. Even in Vancouver, of three Buddhist temples contacted by Xtra, not one had performed a gay wedding.

So it was with understandable nervousness that Huang and You approached their Buddhist teacher, Zhao Hui, with their proposal. But they need not have worried. Zhao Hui was more than happy to see a loving, committed couple married in a Buddhist ceremony.

“She was delighted,” Huang says. “She supported us absolutely . . . She even offered to let us hold the wedding right there at the seminary.”

According to Huang, Zhao Hui stresses the importance of reasonableness and moderation in spirituality. As a teacher, she lets her students think for themselves and come to their own moral conclusions. “Zhao Hui didn’t think there was anything special or different about our relationship,” Huang says. “We’re partners. It’s love. There’s no difference.”

For Taiwan as a whole, however, this was a very different kind of marriage. The news of Huang and You’s engagement quickly landed in Chinese language papers in Taiwan, Hong Kong and around the world. The wedding became not just a ceremony, but a symbol.

Huang says the pressure on her and You was enormous. Only months after her engagement, her guest list had shot up to 200 people. Some friends and family — while privately supporting the wedding — told her they couldn’t face all the media attention and publicity.

“I’ve known I was gay for 20 years,” Huang says. “It’s easy for me to face this stuff. It’s harder for my friends and family who have been dragged into the spotlight as well. It’s too bad.”

Now that the wedding is over, Huang worries about her future. “I don’t know how secure my work will be after this,” she says. “I don’t know how people will treat me in Buddhism classes . . . We’ve had to give up a lot.”

But Huang still thinks the public wedding was worth the effort and sacrifice. She says it is important to show Taiwan’s many traditional Buddhists that even Buddhist teachers are getting behind gay rights.

“It was a spectacular wedding,” says Wu Shaowen, from the Taiwan LGBT Family Rights Advocacy. “All those gays and lesbians and their parents and families who were able to come together to support a couple, that’s very important.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra