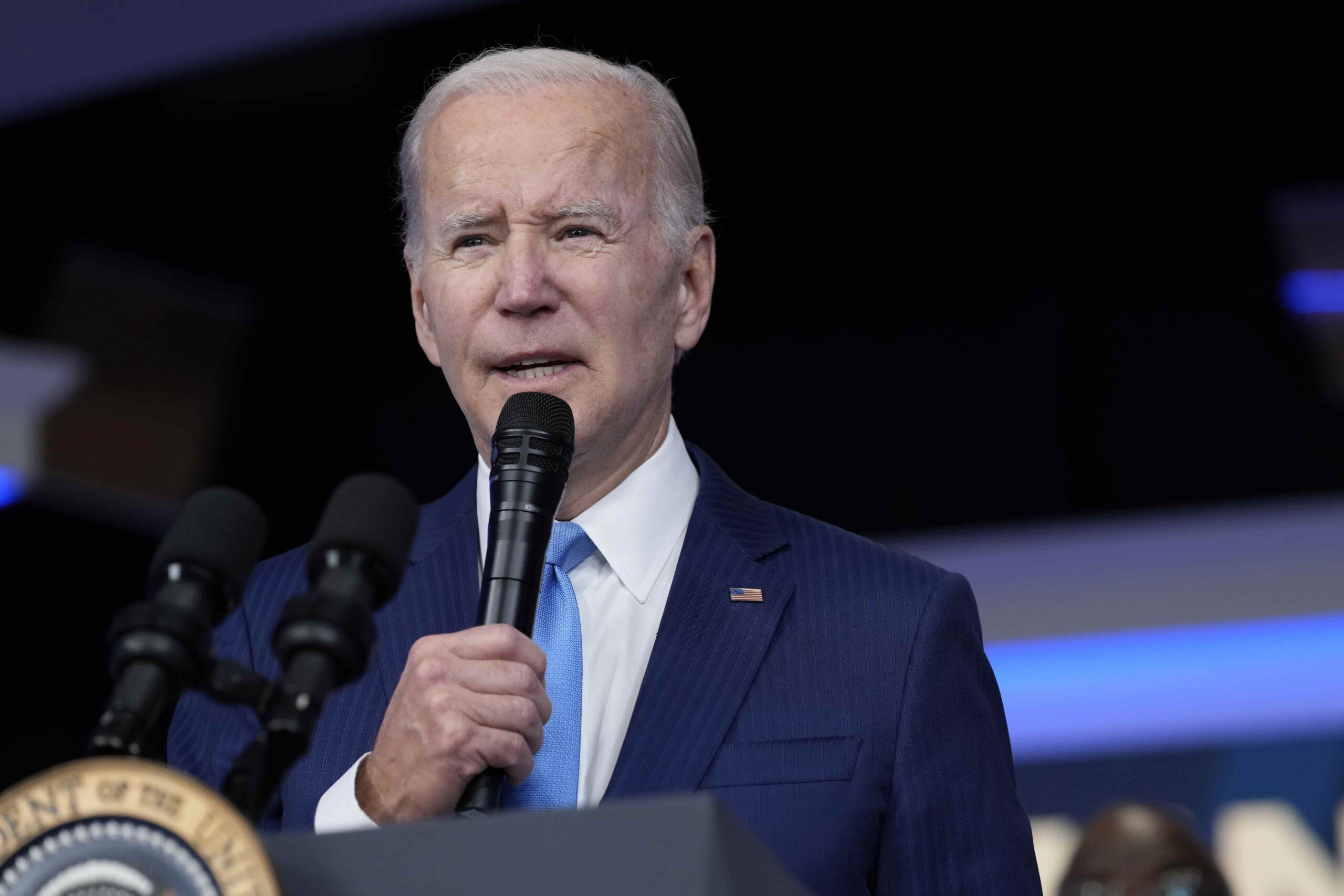

On December 13, President Joe Biden signed the Respect for Marriage Act (RFMA) into law. In a ceremony at the White House, Biden proclaimed the act a “final step toward equality toward liberty and justice—not just for some, but for everyone.” “For most of our nation’s history, we denied interracial couples and same sex couples from these protections. We failed to treat them with equal dignity and respect. And now, law requires that interracial marriage and same sex marriage must be recognized as legal in every state in the nation,” he said.

While LGBTQ2S+ advocates applauded the move in the face of recent threats to same-sex marriage rights, many say the act is far from perfect, and are calling for greater protections in the face of increasing conservative threats to queer rights.

So, what does the Respect for Marriage Act actually do?

Contrary to popular belief, the RFMA does not actually codify the Supreme Court’s ruling in Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized same-sex marriage at the national level in 2015. Rather, the RFMA officially repeals the 1996 Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which defined marriage as being between one man and one woman, and gave states the right to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages in other states.

While Obergefell technically overruled DOMA years ago, the latter remained on the books—meaning that if Obergefell were overturned, federal law would revert to DOMA. Now, in the event that Obergefell is overturned—as Justice Clarence Thomas hinted at in his concurrence to the Dobbs ruling in June—the RFMA would require that all legally performed marriages be recognized across state lines.

This also means that queer couples would be able to cross state lines to obtain a legal marriage, which their home state would then be forced to recognize. The RFMA also secures these rights when it comes to interracial marriages, which were also threatened under Thomas’s concurrence.

If Obergefell were overturned, same-sex marriage would become illegal in 25 states nationwide: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah and Wisconsin, according to the Movement Advancement Project (MAP). Under the RFMA, couples who were already married in those states will remain married if Obergefell is overturned.

Why are advocates concerned about Obergefell?

When the Supreme Court overturned the landmark abortion case Roe v. Wade in their ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization in June, conservative Justice Clarence Thomas issued a worrying concurrence in which he took aim at several crucial precedents: Griswold v. Connecticut, which secured birth control access; Lawrence v. Texas, which overturned sodomy laws; and Obergefell. As all these precedents were decided on the same basis as Roe, Thomas argued that they should be “reconsider[ed]” and called them “demonstrably erroneous.” While not mentioned by Thomas, legal scholars have noted that Loving v. Virginia—which secured the right to interracial marriage—could also be in jeopardy.

Thanks to the increasingly conservative makeup of the Court, advocates say it’s highly likely that conservatives will use the Court to try to chip away at LGBTQ2S+ rights. This has already proven true, with the Court hearing arguments in at least one case thus far this session that would foreground religious freedoms at the expense of queer rights.

What else should you know about the RFMA?

The RFMA includes significant religious exemptions, which were crucial in attracting Republican support for the Act in the Senate in order to bypass the filibuster. These ensure that any house of worship has the right to refuse to perform a same-sex wedding if it goes against their beliefs.

While advocates celebrated the Act’s passage, many say it’s far from enough, in the wake of the Supreme Court’s threats and a rising tide of anti-LGBTQ2S+ legislation in statehouses across the country.

Advocates point to the long-delayed Equality Act as an example of a better way to secure LGBTQ2S+ rights in the face of a hostile Supreme Court. The Equality Act would codify federal discrimination protections on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity into civil rights law. However, it has failed to receive the support it needs to make it through the Senate since it was first introduced in 1974—and there is little confidence that the upcoming Congress will have the votes to usher it to Biden’s desk.

The American public largely supports same-sex marriage, with a Gallup poll noting an all-time high approval of 71 percent earlier this year.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra