"A level playing field is an illusory concept to begin with," says the CCES's president and CEO, Paul Melia. Credit: Erik van Leeuwen

Sports in Canada is about to undergo a big transition, if the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) has anything to say about it.

The group released a report Oct 23 that makes numerous groundbreaking recommendations on gender expression and identity. It suggests that all levels of sports associations should let players compete as whatever gender they identify as.

The 35-page report, entitled Sport in Transition: Making Sport in Canada More Responsible for Gender Inclusivity, will surely shake up the discussion around gender identity in a field that has recently found itself facing some tough decisions about how to classify gender.

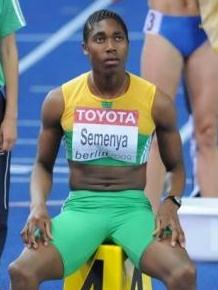

Just before London’s games, the International Olympic Committee drafted new regulations that set testosterone levels – not an athlete’s self-identification – as the metric for determining gender. That decision was born out of controversy, after South African runner Caster Semenya’s sex was called into question during a 2009 competition in Germany. The track and field governing body required her to undergo “gender testing.”

This report is looking to ensure that does not happen in Canada.

“This desire to definitively demarcate sex has proven to be scientifically elusive,” the report reads. “Of much more serious concern, it has also been harmful for some of the athletes ensnared by the ill-considered, usually inconclusive testing.”

The report looks to eliminate “fairness” as a barrier to stop intersex and transgender people from competing.

The report argues that it’s “Cold War suspicions that presume athletes with variations of sex development are motivated by cheating and must be policed.” It looks to dispel those suspicions by fostering dialogue and inclusivity.

“A level playing field is an illusory concept to begin with,” says the CCES’s president and CEO, Paul Melia. He says there’s no evidence of a professional athlete ever competing as the opposite gender to gain an advantage. He adds that sticking too rigidly to “male” and “female” creates “arbitrary exclusion.”

The idea that such Juwanna Mann-style antics are actually happening leads to “public shaming” of the athletes, Melia says.

The CCES’s tactic isn’t to establish a series of policy proposals, Melia says, but instead to encourage sport associations to “welcome the diversity” and hammer out their own proposals, taking the report as more of an inspiration.

Melia and the CCES set up an expert panel to draft the report. Fifteen representatives from the medical, trans, sport and women’s communities came together to establish the document. The goal was to bridge the gap between professional organizations and a science-based approach to dealing with trans and intersex people in sports. Two representatives were brought in from the professional curling league in Canada, an association that has dealt with these issues before. The panel also included a trans person, several doctors and a representative of the government.

Now that the report is out, Melia says, they’re looking to open a dialogue.

“The report can help inform all sport associations – from the [International Olympic Committee] down to a local soccer association,” he says. That’s all a part of their “playground to the podium” approach.

Melia, however, is realistic.

“We understand what the status quo is,” he says, noting he doesn’t expect the IOC to wake up tomorrow and draft trans- and intersex-inclusive regulations. The debate, he says, is what’s important – and what will change minds.

“This can be a mind-stretching idea for people,” he says.

The group doesn’t have much of a budget to take their message on the road, so they’re bringing the road to them. They’ve set up a comment section below the report to encourage dialogue on the issue.

Those wishing to join the debate can do so on the group’s website.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra