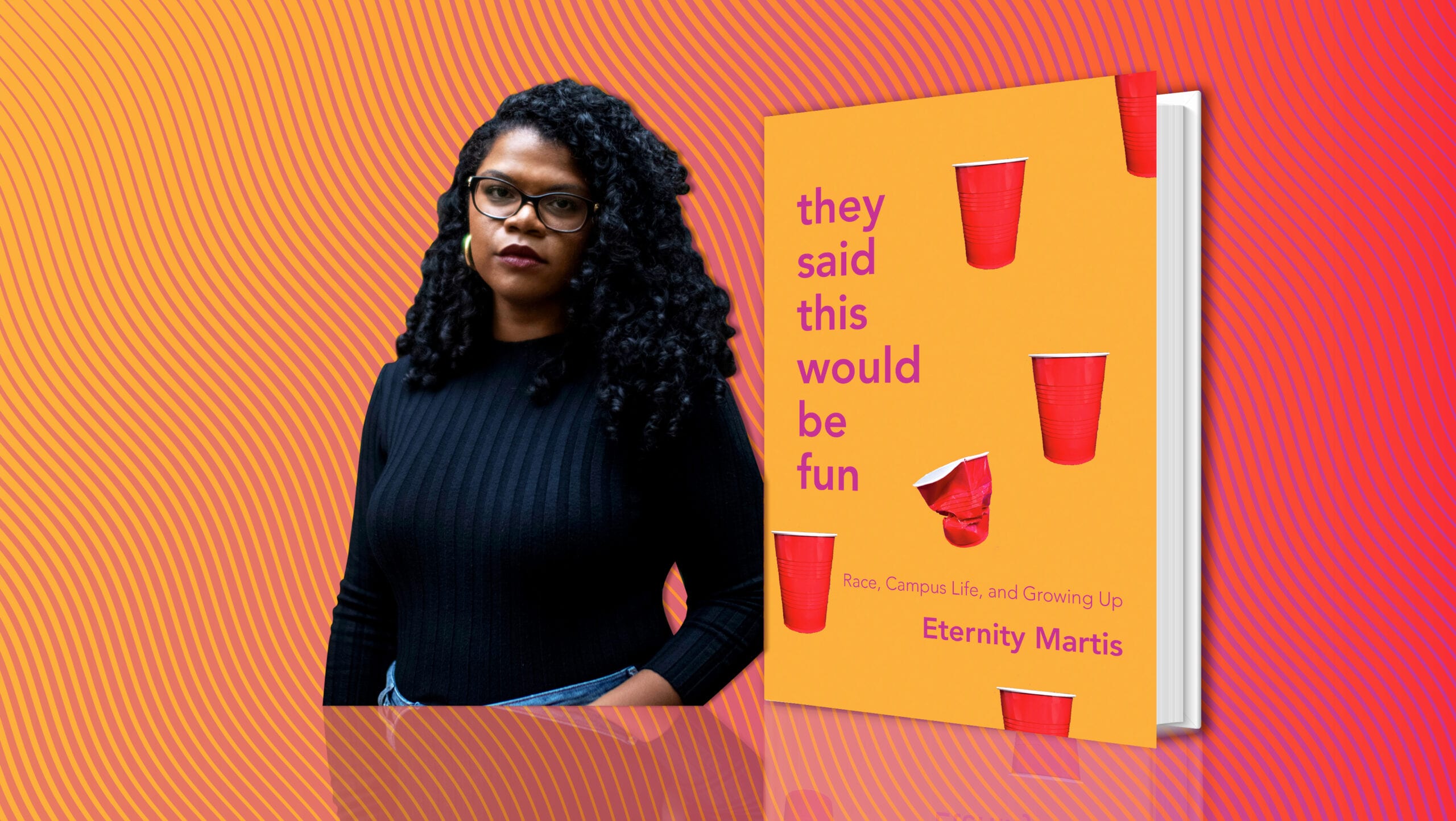

Award-winning journalist and Xtra senior editor Eternity Martis’ memoir, They Said This Would Be Fun: Race, Campus Life, and Growing Up chronicles her life as a young Black woman in a predominantly white university. It explores the complexities of relationships, sexuality and race. The following excerpt is adapted from the book’s introduction, where Martis debunks the myth of student life being a “fun” experience for all young people, the insidious nature of university towns, and being the first in her family to go to a Canadian university.

As I launched out the window of an inflatable bouncy castle, into the warm autumn air and then the mud below, the only thought undiluted by copious amounts of alcohol was: This is what freedom feels like.

It was Saturday, the last night of Orientation Week, and hundreds of first-years were coming together to celebrate on University College Hill, a giant grassy quad on campus. Western University was known for having the most epic frosh week in Canada, especially on the last night, when a B-list Canadian band always played. This year, it was Down with Webster. Sex with Sue, the infamous old lady who we watched after-hours on TV while our parents slept, would show us how to put on condoms, and loud music would play all night alongside carnival games, corporate sponsors and their free grub, and bouncy castles.

A week ago, I had been sobbing in the basement of the house where I grew up, clutching my high school boyfriend’s tear- and snot-stained shirt and cursing myself for thinking I could handle moving away from home. I cried the whole way to London, past the small cities I had never heard of and the luscious Green Belt. I cried as I walked up to my new room in Medway-Sydenham Hall and looked at the small space, crammed with two twin beds and two desks, that my best friend Taz and I would be sharing. I cried as I unpacked boxes, as I put my mattress protector on, as I wiped down empty drawers, as I unloaded my underwear from the vacuum-sealed bag and folded them neatly. I cried as I closed the drawer. I cried when I realized there were no other brown-skinned girls on our floor besides us. I cried so much that my floormates and their parents were calling me “the crying girl.”

The welcome package had given us tips on how to pack, but it didn’t specify how much we needed to bring. My family didn’t know either—I was the first and only one to go to a Canadian university—so I brought every bra I owned, every spare sock, pair of shoes, and picture frame from my bedroom. It took twice as many sophs, the volunteer students who help first years adjust to student life, to haul my stuff up to the third floor and make it fit into the shared fifteen-by-twelve-foot space. At one point, they lost the bag full of my pants and I was inconsolable, thinking that I’d have to walk around pantless because nobody would sell fashionable bottoms in a place nicknamed “Forest City.”

“It had never occurred to me that other cities in Ontario wouldn’t be as welcoming as the one where I’d grown up.”

When I had told people back home that I was going to Western in the fall, they had similar comments: It’s the best school. It’s a party school. It’s a white school—why would you go there? Their eyes widened and they’d lean in, whispering as if they were afraid of someone hearing, and say that London was notoriously white, Christian, and conservative. They told me cautionary tales of family and friends transferring out of the school after years of microaggressions and racial harassment on and off campus. “Don’t worry though,” they’d say with a smile. “You’ll have fun.”

It had never occurred to me that other cities in Ontario wouldn’t be as welcoming as the one where I’d grown up. In Toronto, there was always a mix of various ethnicities—Chinese, German, Filipino, Trinidadian, Somali, Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Jamaican, Guyanese. You can find numerous types of cuisine, schools, and places of worship on any given block. All around, people look like you and look unlike you and it’s nothing to fuss about.

But listening to people’s concerns, it was like I had chosen the Alabama of Canada to spend the next few years of my life in. It wasn’t that my hometown was exempt from racism—I knew which department stores would send their white employees following after me like a criminal, and I understood the intentions of the police when my peers would get stopped on their way home from playing basketball. But I was sheltered; I hadn’t gotten a complete picture of what it meant to be a Black girl at home before I left to become a Black woman in London. I wondered if I could form my own identity surrounded by white kids wearing Hunter boots and Canada Goose jackets. I worried I could be alienated for being “too Black.” I was even more worried about losing myself and being called “too white” when I got back home.

But people in London were friendly. They smiled as you passed by. Strangers said good morning. Everyone talked to me—the women in line at the grocery store; the people sitting next to me at a restaurant; the students also waiting an unacceptably long time for the bus. But many of our conversations ended up diverting into race. We don’t get a lot of Black people here. London has become very progressive in the last few years. My God, Black people are just so funny. Where are you from? No, no no, like where did you originally come from? Ethiopia? Kenya? Zimbabwe? Africa? As the months and years went on, these seemingly innocuous comments became more ignorant, and at times, malicious.

From the ages of 18 to 22, I learned more about what someone like me brought out in other people than about who I was. I didn’t even get a chance to know myself before I had to fight for myself.

“From the ages of 18 to 22, I learned more about what someone like me brought out in other people than about who I was. I didn’t even get a chance to know myself before I had to fight for myself.”

In the four years I spent in London, Ontario, for my undergraduate degree, I was called Ebony, Dark Chocolate, Shaniqua, Ma, and Boo. I encountered Blackface on Halloween and was told to go back to my country on several occasions. I was humiliated by guys shouting, “Look at that black ass!” as I walked down a busy street. I was an ethnic conquest for curious white men, and the token Black friend for white women. I was called a Black bitch and a nigger. I was asked by white friends desperately trying to rap every song off Yeezus if it was okay to use nigga around me. I was verbally assaulted and came close to being physically attacked by angry men. I came face-to-face with a white supremacist. I was asked if I spoke English and whether I was adjusting to Canadian winters. When I told people I was born in Canada, they’d impatiently badger me with, “But where are you really from?”

These encounters were about how I was perceived, not who I actually was—someone always in between worlds: A Canadian-born girl with two immigrant parents; a multiracial woman with Black features in a family of brown people; a daughter raised by a working-class mother and middle-class grandparents; the only baby born out of wedlock in a family all conceived after marriage; an only child with at least seven half-siblings; an astrology-lover born right on the cusp of Taurus and Gemini.

I have lived in the squishy middle all my life, at the margins of binaries—an experience that has made me as independent as I am lonely.

I felt trapped by these categories, whose walls felt so high that I might never get out. I wondered what kind of person I was outside those confines, and university seemed like a good place to start solidifying the pieces of myself that I felt I couldn’t explore back home.

A few things did solidify about my identity while I was there: I was Black, I was a woman, and I was out of place. I didn’t identify as Black until I got to London. This is common among people who come to Canada from countries with diverse ethnic communities, or who grew up in a mixed family where identity wasn’t discussed. I wasn’t ignorant to my own appearance; I definitely didn’t pass as white, and there was no way I looked Brown. At home, being a racial minority meant you belonged somewhere. In London, it was a marker of exclusion and difference, and you were squeezed into a category—Black, White, Asian, Brown— that became a way to navigate and survive the environment.

“A few things did solidify about my identity while I was there: I was Black, I was a woman, and I was out of place.”

My maternal grandparents, who raised me for the first half of my life, faced racism themselves when they arrived in Toronto from Karachi, Pakistan, in the early 1970s. But they didn’t know what to make of my claims of anti-Black racism. We never spoke about my father, a Jamaican man, who was absent, or what his ethnicity meant for my own identity. My family was shocked to hear me call myself Black, and even more shocked at the stories I told, despite police-reported hate crimes across the country soaring the year before I went to Western, and London having one of the highest rates of all Ontario metropolises. It was 2010, and we were only starting to get to a place where advocacy journalism and personal essays extensively covered these problems. Modern Black writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, Kiese Laymon, Morgan Jerkins, Reni Eddo-Lodge, and Ijeoma Oluo had yet to get the recognition they deserved—or even to write their stories. I had few examples to prove racism was a common occurrence and not an isolated experience.

My family thought that perhaps I was exaggerating. That I had developed a new, somewhat militant eye for race issues. Plus, I was so angry these days—maybe my irritability, they gently offered, was causing me to misunderstand people’s intentions.

Of course, I was angry. Instead of focusing on classes and adjusting to my new life as a student, everything had become about the skin I was in. I became a survivor of both inter-partner violence and sexual assault, and had to fight stereotypes about not being the perfect victim. Anger and fear were so etched in my body that I often felt I had no control over myself. Why could people take their anger out on me, but mine was irrational?

I internalized people’s doubts about my experiences. I grew stressed, anxious, and depressed, coping with food, alcohol, and partying. In public, I devised exit plans in case I was harassed. Everywhere I went, even in my own home, I felt a constant, electrifying pressure in the air, as if violence could erupt at any moment.

I kept a record of all the instances where I had been the target of discrimination, harassment, and microaggressions, scribbling them down on pieces of paper—notes to myself, a way to make sense of what was happening. At school, I naturally gravitated towards students of colour who were having similar experiences. Some couldn’t make it, even with our support system, and they dropped out or transferred schools. I decided to stay, weighing up the discomforts of starting over someplace new and the discomfort I was already familiar with. I accepted the emotional cost of this decision.

The year after I graduated from Western, I wrote a reported personal essay for Vice Canada, titled “London, Ontario, Was a Racist Asshole to Me.” I interviewed current students, city councillors and locals. The essay sparked heated discussions in homes, in city council, and in universities, and is still a point of reference for media when discussing race-related issues such as carding, the illegal police procedure of randomly stopping people of colour and collecting information.

I received hundreds of messages from people who read the article. Londoners promised to be better allies. People who had witnessed the racial harassment of friends asked for advice on how to intervene. Older folks recalled their experiences from decades ago, saying things hadn’t changed. People of colour of all ages and backgrounds shared their own stories.

Londoners confessed secrets about the tricks their bosses used to keep Black people out of their establishments. Women and LGBTQ2+ people told me about their own horrible experiences, from verbal slurs to physical assault, especially in nightclubs. Former residents of London told me they’d left because the racism was so bad. Current inhabitants told me that they were afraid for their lives.

“For many of us, the whole university experience—the independence, parties, exploration, sex, wild nights—may not be possible.”

Most of all, students attending other post-secondary schools in Canada shared their experiences and concerns, many of which mirrored my own. And high school students messaged me, worried about which colleges and universities were racially tolerant. In the years following the article’s publication, I’ve met students of colour around the world who’ve told me stories of the racism and isolation they experienced while attending university in the U.K., Australia, and the U.S.

To be clear, this isn’t just a Western University problem. Here in Canada, we have nearly one hundred universities and even more colleges, and yet there’s no evidence that we collect race-based data on students, so it’s impossible to know how many are visible minorities and what their needs and challenges are. There is also no unified, formal policy across schools on dealing with racism. Many students don’t report incidents because they fear they won’t be believed.

When our experiences are treated like they don’t matter, we learn to deal with them ourselves, especially when the institutions where we spend the first years of adulthood aren’t equipped to support us. But young people in post-secondary institutions today are up against a host of serious, life-changing issues.

In Canada, university-age young women face the highest rates of sexual assault and inter-partner violence in the country, and are stalked, cyberstalked, and harassed more than any other age group. Carding disproportionately affects young Black and Indigenous men. Young people living with a shaky socio-economic status are pressured to get a degree, and both have been linked to an increase in mental health issues. Racism and discrimination have devastating physical and mental health effects on students, which is linked to poor academic performance and dropout rates. And we are experiencing all of this while navigating the school system. Before our brains have even finished developing. Before we even get to know who we are.

So yes, our experiences matter. This shit is actually happening right now to our young people.

On top of all that, students of colour are living and studying during a time when the far right is using universities to its own advantage. Endless stories have made the news: white pride groups putting out pro-white flyers on campuses; white nationalists using university spaces to spew anti-immigration, anti-LGBTQ2, anti-woman hate under the guise of free speech; hate groups trying to convert young, angry men into joining their cause. All this coverage highlights white supremacy, not the students living under it.

We promise students that university will be the time of their lives, that they will come to know themselves, that it will be fun. But for many of us, the whole university experience—the independence, parties, exploration, sex, wild nights—may not be possible. Not when we may deal with racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, and assault—physical and sexual—from our peers and the people around us. This perceived utopia can also be unbearable and unsafe.

“I hope this book will be an urgent reminder that dismissing the experiences of young people today will have serious, permanent implications for our entire society.”

I wrote this book to bring attention to what is happening inside our schools. For years, I’ve collected these moments, trying to find the right format—a play, a blog, a novel—but nothing seemed more fitting than a memoir. I’ve used my own experiences, as well as examples from across Canadian universities, to illustrate that this is a nationwide issue that demands attention.

Thanks to the generosity and selflessness of my grandfather, I’ve had the privilege of going to university, an opportunity and luxury I know many do not have. I hope to put this privilege to good use here, by illuminating the not-so-secret lives of university students: the messy, complicated, exciting but harrowing experience of what it’s like to be a student and woman of colour today.

Nothing in this book is sugar-coated for you. It’s raw. It’s glaring. It’s imperfect, as is real life. I did not make all the right decisions, or all the smart ones, and I’ve made peace with that. I have done my absolute best to recall everything as accurately as I can. At times, this book is distressing, and at other times you will laugh. Some events may bring back painful memories of your own.

I have chosen not to hold back because, for so long, young people have been infantilized and shamed for talking about the things that affect us. We’re told we haven’t worked long enough, lived long enough, been through enough to have our own pain validated. I hope this book will be an urgent reminder that dismissing the experiences of young people today will have serious, permanent implications for our entire society.

Finally, this book is for anyone, past or present, who has struggled to make sense of their post-secondary experiences.

For those of you who feel alone and unheard. For those of you who want to learn more, and for those of you who courageously speak up and tell your stories, even in the face of denial and harassment. And this book is especially for those of you who came out at the other end, broken but not beat, resilient but still soft.

I see you.

They Said This Would Be Fun comes out March 31.

Excerpted from They Said This Would Be Fun by Eternity Martis. Copyright © 2020 Eternity Martis. Published by McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra