This story is part of “Still Fighting”, a series exploring the past 50 years of LGBTQ2 activism in Canada.

As a writer, Gerald Hannon sings both the body electric and the body politic; his work mixes sexiness and activism in equal parts. His pieces document and interpret some of the biggest events in queer history — the 1981 bathhouse raids in Toronto, the AIDS crisis — that helped form aspects of this community of communities. In 50 years of work for Xtra and its predecessor, The Body Politic, as well as some of Canada’s most important mainstream outlets, Gerald has turned an unabashedly queer eye on the world, demonstrating a novelist’s ability to notice and convey the most telling of details.

As I page through an assembly of his greatest hits, I try to keep in mind the individual behind this distinguished body of work, printing up a portrait of him as a young man. It’s borrowed from his Facebook page: He’s sporting snazzy checkered pants, his big blue eyes dreamy behind his specs, his hair shoulder-length and floppy.

The places that young man would go, taking readers from bathhouses to opera houses, dog shows to late-night cruising spots. In one breath, he describes visits to the opulent homes of Rosedale hostesses; in the next, the pre-mating rituals of horny gay guys at a dive bar.

But it’s his renderings of people, rather than places, that he’s most known for — giving carefully reported, highly literate takes on those who’ve made Toronto the place it is today. Until Gerald* has written about you, you can’t really claim to be anyone in this city. Over the course of his career, he’s won a staggering 13 National Magazine Awards.

His qualities as a journalist, though, seldom get much space in stories about Gerald. His Wikipedia profile is a typical example: It’s almost entirely devoted to the two main scandals he’s weathered.

The first came in 1977 when he published a piece for The Body Politic about pedophilia — one that is an apologia for it in certain circumstances — and was prosecuted for it. Police raided the publication’s offices, collecting information about subscribers and advertisers, and charged Gerald and two others with “using the mails to distribute immoral, indecent or scurrilous literature.” His acquittal, 40 years ago, and the acquittal of Pink Triangle Press, the former owner of The Body Politic and current owner of Xtra, is widely considered a landmark case in the laws governing freedom of expression in Canada.

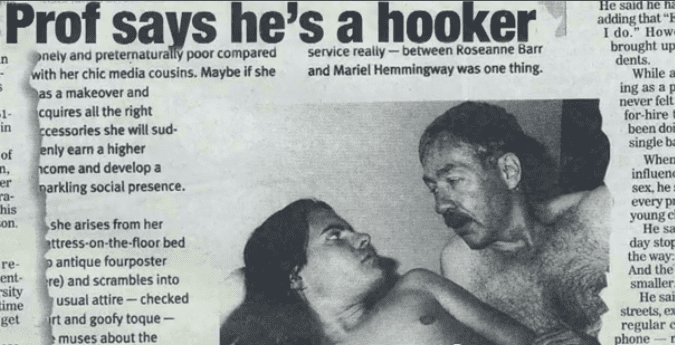

The second scandal followed nearly two decades later, in the mid-1990s, while he was teaching journalism at Ryerson University. Gerald admitted to a reporter from the Toronto Sun, who was poking around for some dirt, that he sometimes moonlighted as a sex worker. Although he had many supporters, the “Hooker Prof,” as he came to be known, was drummed out of the school.

These controversies form a part of Gerald’s legacy — and while he doesn’t shy away from either one, they’re not his whole story and aren’t, in my mind, even the best parts of it. His has been one of the most up-and-down-and-up-again careers in Canadian journalism history, and one I’ve followed closely for years. His work conveys a sense of Toronto’s explosive growth and change. Through his now 75 years — his birthday is today, July 10 — Gerald’s not only been a witness to gay history in Canada, but a prime mover of it.

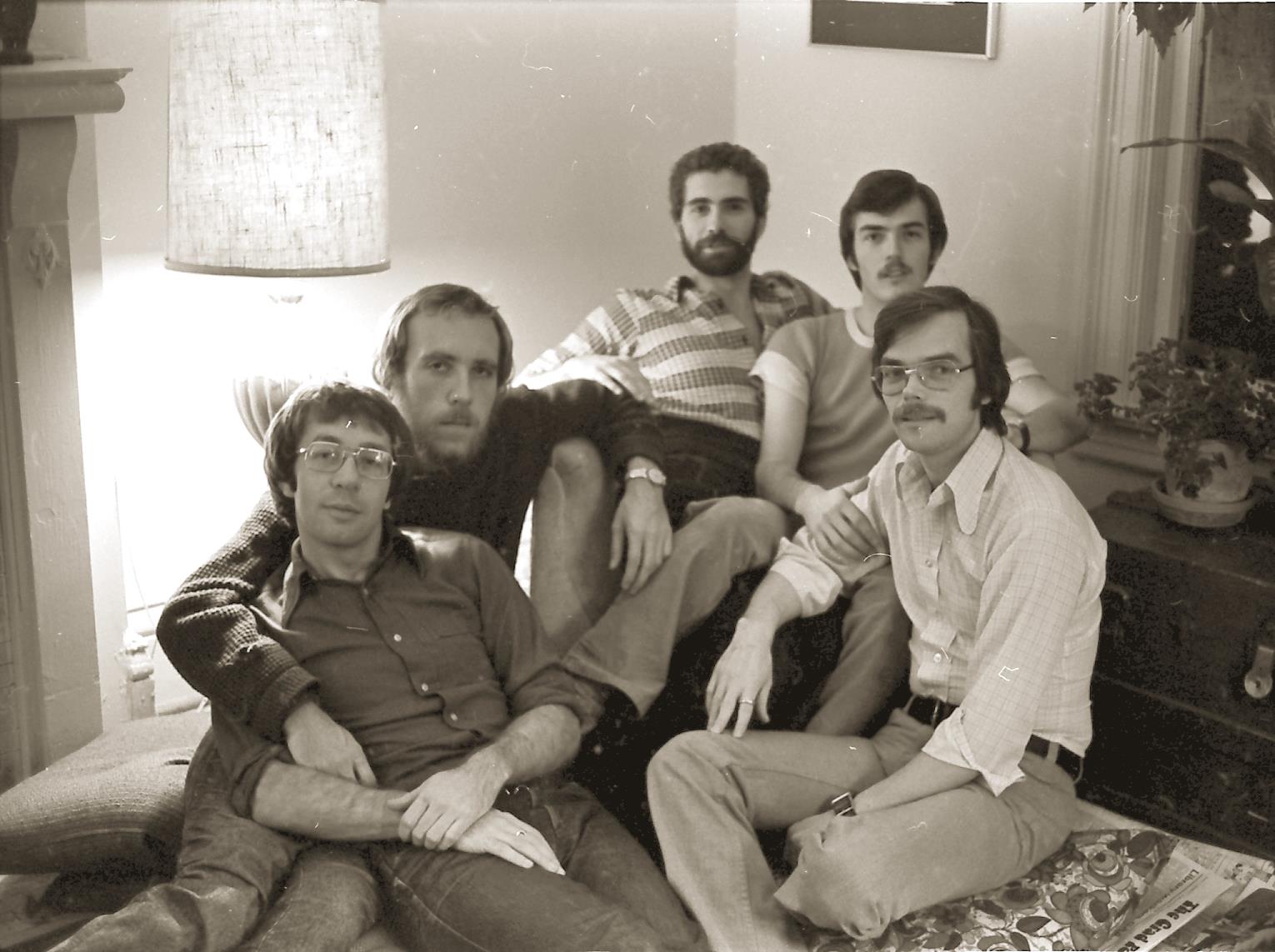

The Body Politic collective household at 48 Simpson Avenue in the Riverdale neighbourhood. From left: Gerald Hannon, Robert Trow, Herb Spiers, Merv Walker and Ed Jackson. Credit: Courtesy of the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives

The photo I’ve printed of him was taken not too long after he got off the train at Union Station in 1962, from a small town on the north shore of Lake Superior called Marathon. He came to the city to study with all the other Catholic boys and girls at the University of Toronto’s St Michael’s College. There, he says ironically, he lost his religion. After growing up in a house with few books or magazines, he started to find himself as a reader, then a writer.

His childhood and youth were tough. His alcoholic father sometimes beat him and his mother, and his doctor sexually abused him. When I ask him about his childhood, he packs a lot into a couple of sentences: “Did you know my mother came out as a lesbian?” he says. “She eventually left my father for a woman she worked with at the hospital . . . She moved to Toronto and he came after her, intending to get her back. He died [in 1977] in a bar car, an appropriate death for a drunk.”

“Controversies form a part of Gerald’s legacy — and while he doesn’t shy away from either one, they’re not his whole story”

Gerald didn’t walk off the train from northern Ontario, hands aloft, ready to fall into the welcoming arms of the gay community. Coming out took some time and some encouragement from his friend (and first male lover) Ed Jackson. The pair saved up for a trip to Europe — they both remember being excited and scared when they joined, in 1971, an early gay-rights rally in London, England. What if someone from home spotted them in photos of the march? The worry wore off, but the thrill of being part of this new movement did not; when they returned home, both began writing for the fledgling Body Politic — which had launched that same year — joining the collective while living and working together on it.

The early issues, which have been collected online by the Canadian Museum of Human Rights, feature Gerald’s homoerotic love poetry as well as his reports on the growing queer community. A photographer as well as a writer, Gerald’s photos of that time bring you into the thick of gay liberation’s early days: from the marches and in-your-face public displays of same-sex affection, to the angry riots and chatty (probably catty) annual Toronto Island picnics — precursors to the mega-festival that is today’s Pride.

There wasn’t much of what we now call intersectionality in the mix. The writers of the time were mainly white men (with the notable and ultra-talented exceptions of Chris Bearchell and novelist Jane Rule) from working and middle-class backgrounds.

There was a great sense of play on offer during that period — “I’m Forever Chasing Rimbauds” is the headline of a piece about the queer symbolist poet Arthur Rimbaud — as well as a strong desire to provoke.

And so, in 1977, Gerald published “Men Loving Boys Loving Men.” In the piece, he profiled three men who had sex with boys and adolescents, as well as one boy, the former object of a older man’s sexual attention, who’d grown up. The province launched a criminal case against Gerald, Ed Jackson, collective member Ken Popert and the Pink Triangle Press for the possession and distribution of obscene materials. As a result, The Body Politic went from being a paper serving a small but growing community to an internationally known outlet, the centre of a cause célèbre.

Civil libertarian lawyer Clayton Ruby took on the case and convinced a judge to dismiss the charges in 1979. In his reasoning, Judge Sydney Harris wrote: “I must judge with objectivity and concern for the right of free discussion and dissemination of ideas unless there be a clear incitement to illegal action.” The then-attorney general, Roy McMurtry, appealed the ruling without success.

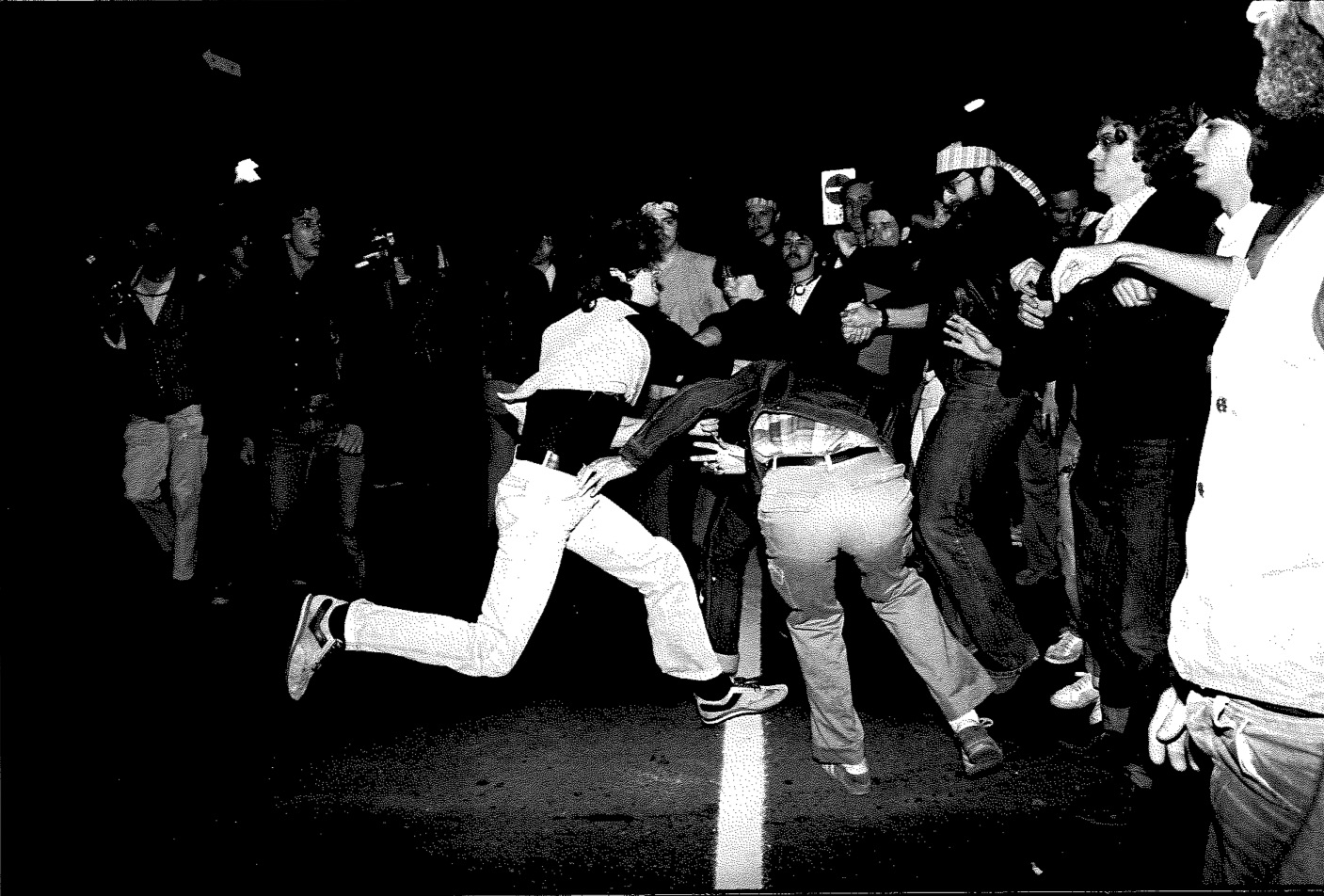

The publication’s acquittal and survival meant it was still active two years later when, in February 1981, Toronto police raided four gay bathhouses and arrested nearly 300 men — one of the largest mass arrests in Canadian history. Gerald and the other members of the Body Politic collective decided they had to respond, both as reporters and activists.

“Gerald doesn’t try to make gay sexuality palatable for Toronto Life’s establishment (or aspiring-to-be-establishment) readership; he never panders”

“It was scary,” Gerald recalled in a recent speech. “We went to every bath . . . and there was a police car outside every one of them and a paddy wagon outside of several of them, and men were being shoved out the door and shoved into the back. They had brought in sledge-hammers and crowbars and smashed the place to shit.

He says now: “We had to be both the paper of record and a centre for organizing — we had the only phone number and office of a gay organization.”

Using that phone and its network, the collective played a key role in organizing a protest the night after the raids. “We turned up at midnight, terrified that no one would come,” he says. “But within half an hour the place was packed; within 40 minutes, there were thousands. And we were suddenly marching down Yonge Street, taking it over,” before heading to Queen’s Park.

Again, the province’s top lawman McMurtry played a central role, his Crown Attorneys prosecuting the men found in the bathhouses. He told the Toronto Sun at the time: “They know the public is frightened by homosexual militancy and by their proselytizing, but they seem to enjoy feeding their fear.” The ensuing protests, though, generated sympathetic editorials from other local papers, and most of the men were ultimately acquitted.

And then, just as the community started to rise up and feel its power, along came a mortal ailment, the so-called “gay cancer,” AIDS. In one of his first big features for a mainstream publication, “Gay After AIDS,” published in 1988, Gerald documented the disease’s ravages for Toronto Life.

In high Hannonian style, the piece takes readers on a late-night cruise through some of the city’s parks after Pride. “Hot summer night. Come with me. The crowds are gone, but the park is not empty. No downtown park in Toronto ever is, not after one or two in the morning anyway. Him? Walking his dog. Really. For now, anyway . . . It’s like silent cinema — nobody ever talks, but everyone understands everything. Like those four guys — standing around in a circle, slowly jerking off. We could join them, and maybe we’d be wrong for it, and they’d just drift apart.”

Gerald doesn’t try to make gay sexuality palatable for the magazine’s establishment (or aspiring-to-be-establishment) readership; he never panders. Among the story’s many emotionally moving bits — a now-dead friend of Gerald’s reading aloud the names of the then-dead at an AIDS memorial; a vigil for a dying friend — is a plea that the dreaded disease not send everyone scurrying towards vanilla lives. “Promiscuity teaches,” he writes. “Gay culture is, among other things, the culture of promiscuity.”

There’s plenty more raunch that follows where the cruising scene led. “I can’t believe we got away with it,” said the editor of the piece, Lynn Cunningham. “For me, he was this guide to the night.”

I take pleasure in imagining some suburban man, a good husband, father and provider, cracking open another, later edition of Toronto Life to find Gerald’s accounts of the legendary Underwear Parties once held at the now-shuttered gay bar, The Barn. “The dance floor is small and that’s the way you want it,” he writes. “It’s small enough that you might feel someone’s breath on your shoulder. It’s small enough that you can’t miss those two hunks in jockstraps enjoying a languid bulge-to-butt pas de deux.”

A newspaper clipping about Gerald Hannon's sex work. Credit: Clip obtained by Andrea Houston

After losing many friends during the AIDS crisis, Gerald encountered a professional setback: he was fired from his teaching job at Ryerson for his side-hustle of, well, hustling. He worried that he might seem untouchable to editors of mainstream publications, but most kept sending work his way. “Why would we stop employing Gerald?” Toronto Life’s longtime editor John Macfarlane says. “That would be self-defeating. You want your readers to love your magazine. Anyway, if you had to administer a morality test to all of your writers, well . . .”

A longtime friend of Gerald’s, the artist and curator Peter Kingstone, says, “He’s watched — he’s helped Toronto grow up on these issues.”

“It’s not always easy being the subject of one of his pieces — those big, blue eyes miss so little”

And so, with the backing of some key editors in the 1990s and 2000s, Gerald came into his own as the city’s premiere profile writer. He’s had his way with politicians of all persuasions, with architects, with many of his fellow journalists and with practitioners of various art forms — from the divas who perform his beloved operas to artists like Edward Burtynsky, Betty Goodwin, Tom Thomson and Michael Snow. (“The main thing in his visual arts pieces is that Gerald’s got a hard-on for beauty,” his longtime editor Mark Pupo says.) Gerald’s “Toronto Lives” collectively create an image of the roast-beef-and-Yorkshire-pudding town it was when he started working — Toronto the Good, the Queen City. They convey something of how it has developed, how it’s gotten perhaps a little less uptight, how it’s become a city of out queens and assorted queers, one with restaurants offering tasting menus from multiple cuisines.

In a feature profile, Gerald anatomizes society columnist Zena Cherry’s haute WASP world as carefully as his piece on the Underwear Party does his own, gay world. Without animosity, the northern Ontario boy describes the houses and hostesses he visits with amusement and care. “The research for this piece took me to sumptuous country homes, to secluded Georgian enclaves in the heart of the city, sat me more than once beside the voluptuous blue eye of the inevitable backyard pool, brought me Pol Roger when I agreed that I would enjoy a glass of wine.” That bit of phrase-making, the “voluptuous blue eye,” may be as good as it gets in magazine writing, but this is no puff piece. In a quiet way, it illustrates the overweening pride and many prejudices of Cherry’s group — all while being a romp of a read.

His Cherry is both a social doyenne and a hard-working hack who meets her deadlines and gets her copy in. There’s an old adage about intelligence being the capacity to hold two contrary ideas in mind at the same time, and his profiles do this thing of letting different versions of the same person live side by side (which sounds elementary but isn’t).

But it’s not always easy being the subject of one of his pieces — those big, blue eyes miss so little; his talent to communicate his observations, his intuitions and thoughts, so complete.

In the run-up to the 2010 mayoral election, Toronto Life commissioned Gerald to write features about two of the candidates: blustery, conservative Rob Ford and blustery, liberal (and gay) George Smitherman. Although his piece on Ford details the would-be mayor’s many sins and wickedness, it’s sympathetic and humanizing, and devotes a lot of ink to Ford’s football coaching and his efforts to quickly address his constituents’ concerns. It serves up the counterintuitive take that editors of long-form journalism tend to love.

The piece on his fellow gay man, Smitherman, is tougher. Gerald begins with a run-in at the Church Street camera shop with a bullying Smitherman, a shop that the politician once ran, and ends with his classic double vision: “I understand why so many people find Smitherman easy to love . . . I love that there’s nothing small or pinched about him — he’s a big man, with big appetites, big passions, big dreams . . . The problem . . . is that he’s not that easy to like.”

Reached by email, Smitherman clearly hasn’t forgiven Gerald or forgotten his piece, sending a curt response to a request for comment: “The profile felt like being eaten up by one’s own community . . . My experience as a trusted, confidential film processor . . . was quite rewarding and generally positive … so it was very surprising to see that decade-long commitment turned against me.”

Gerald doesn’t apologize for it: “Many others had the same experience [at the photo shop] I did.”

“Something often happens when writers start to work on a profile,” Toronto Life’s current editor Sarah Fulford says. “Either the glamour, the charm of the subject or their power, something starts to affect the writer, and they end up writing the piece for the subject, not for the magazine’s reader. That never happened with Gerald.”

Toronto bathhouse riots. Credit: Gerald Hannon/Xtra

It sometimes seems I’ve been following Gerald my whole life. On the cusp of my own coming out in the 1980s, I remember tearing through his 1988 Toronto Life piece “Gay After AIDS,” intrigued and titillated by its sexiness, but terrified by the disease waiting for me out there. We studied the Body Politic case at the University of Toronto law school in the 1990s, in a then-new Law and Sexuality Class. I went on to practise media law, with a focus on free expression — even in that field, the case was one you needed to know about. After leaving the practice, I joined Toronto Life’s editorial staff, fact-checking and editing Gerald’s work. (When I told him once we had a special rate for his short profiles, he asked me, gently, whether the rate was higher or lower than the norm.)

But there’s one rhetorical place he went to in his early career, before I came of age and became aware of Gerald, where I don’t want to follow him. The last two pieces I read through are his explorations of pedophilia for The Body Politic, both written in the 1970s. The last of the two, which became the subject of the legal case, details the relations between three adult men and several adolescent and pre-pubescent boys. One of them is a 33-year-old teacher who says he has been involved with students at each of his four schools, including a 12-year-old at his then-current school. The teacher claims: “I just want to liberate my kids a little bit and help them find their sexual direction.”

This piece presented opponents of gay rights with the perfect cudgel to take to what was then the community’s main media outlet, solidifying the false idea that gay men pose a larger threat to children than other men do. The first time I went out to a gay bar, barely legal with few street smarts to speak of, an older man tried to override my noes, and I had to fight my way out of his apartment — so the piece hits a sour, still-vulnerable spot for me. And now, in this moment of #MeToo reckonings — a time when we are so much more aware of the scars many of us carry left by once-trusted clergy, coaches and teachers — the article pisses me off, but also puzzles me. It mingles something I put at the top of my list of social goods — the promotion of LGBTQ2 rights — with something that sits right at the bottom — adults taking advantage of children.

Gerald has said, over the years, that a critique of the teacher’s point of view could have formed part of the article. When I bring up the piece, I’m hoping for a full-throated disavowal of it, but he sighs and comments: “I can’t regret its publication. It helped put The Body Politic on the map.” I understand, of course, the free-speech arguments that led a judge to dismiss the charges; that was one of my areas of practice. But I still can’t get my head around why he felt it necessary to write those pieces — and why others decided to publish them.

Working on this profile of Gerald, I’ve sometimes felt like a domesticated house cat standing at the window, beckoned outside by this randy Tom. Come out into the streets. Go out and fuck life, get fucked by it. Our differences are probably partly temperamental, but perhaps also generational. For me, there was no gay before AIDS, and so my natural caution in matters sexual and my huge amount of internalized homophobia made the community’s sexiness (to put it nicely) or its sleaziness (not so nicely) sometimes hard to take. After my unfortunate sexual debut I eventually got there, I found my way into it: I picked up and was picked up, I cruised those parks he wrote about, making up for all that lost time. But I grew to want something else, something quieter, something that was both more romantic and also less work.

Another younger friend of Gerald’s, Gerry Oxford, recently married his partner and says of Gerald and his contemporaries: “The institution of marriage is one they don’t believe in, don’t accept.” For children growing up in the conformist, virulently homophobic 1950s, sexual liberation meant both a liberation from the closet and from families and authority figures who often shamed and brutalized them. It meant they had the right not to be married, not to perpetuate the horror that is the nuclear family, not to hanker after respectability.

An irony: Roy McMurtry, the attorney general responsible for the obscenity and bathhouse raid prosecutions, later became the appellate judge who approved same-sex marriage in Ontario in 2003, even while an appeal to the Supreme Court was pending.

In a 2007 piece for Xtra, Gerald writes about attending an event honouring McMurtry for his role in the gay marriage cases, and a subsequent sit-down he had with the man. In the interview, McMurtry downplays his involvement in the bathhouse raid prosecutions and the Body Politic trial. He claims not to remember the obscenity charges laid against Gerald and others, prompting Gerald to write: “You sure know how to hurt a guy, Roy McMurtry. That trial was my big moment; those were my 15 minutes. I spent weeks in his prisoner’s box in his courtrooms and he doesn’t remember?! It’s like Batman not remembering the Joker. Popeye not remembering Bluto. Godzilla not remembering Bambi. It hurts.”

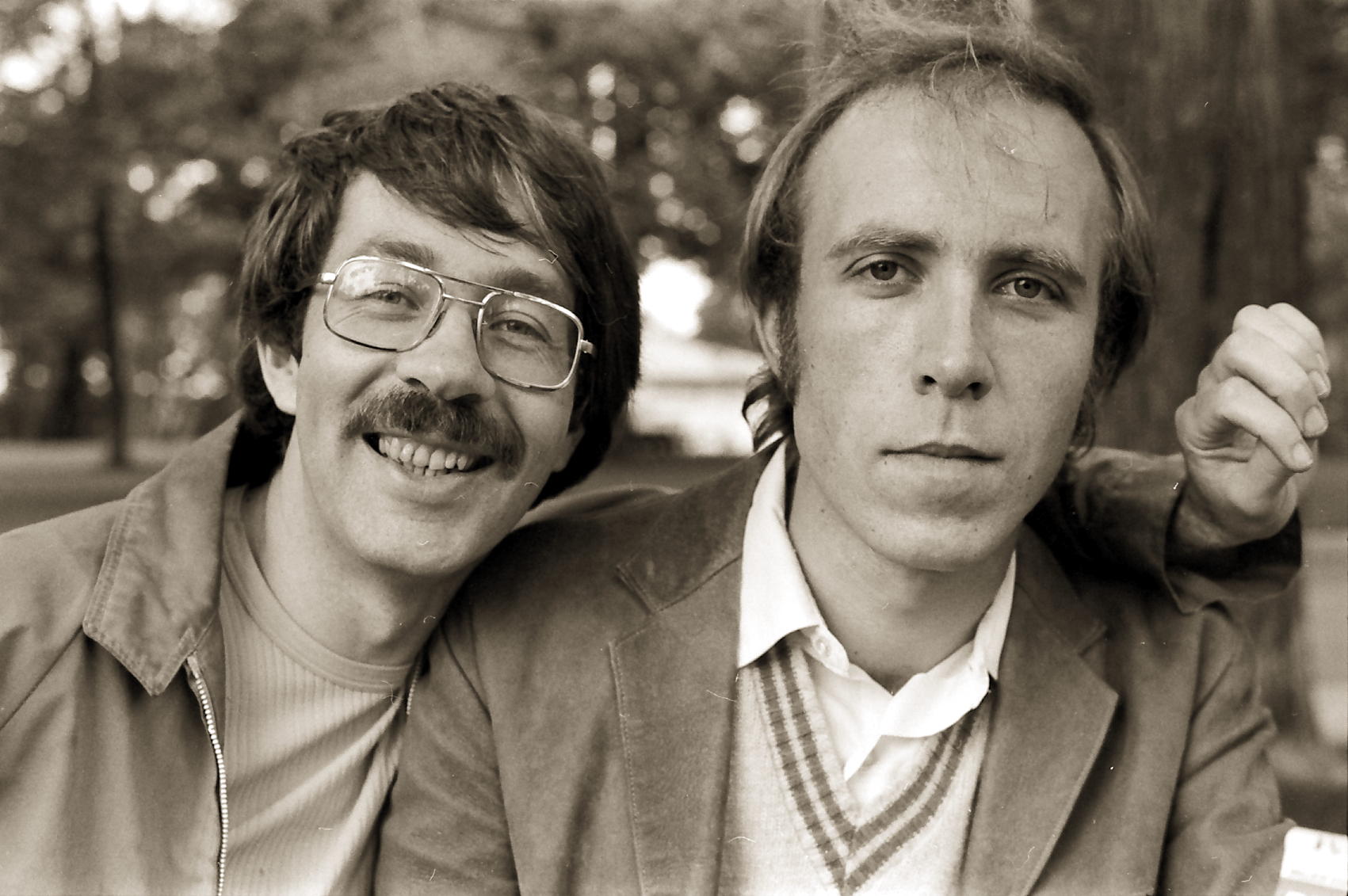

Gerald and Robert Trow, in 1976. Credit: Courtesy Gerald Hannon

The pieces I’ve reviewed for this profile are mostly those recommended by Gerald, his longtime editors and a few of his staunch friends. A few of his pals have formed Team Gerald, a group that is hoping to shepherd a memoir he’s largely drafted into print, and to get a collection of his best pieces published in one form or another. This is essential work if his legacy — important to LGBTQ2 communities and the country at large — is to be preserved, and if others are to have the pleasure of reviewing his pieces. He’s made me laugh, often, and brought me to the brink of tears twice — once with his profile of the late singer Rita McNeil and again with his post-mortem tribute to Rick Bébout, a fellow Body Politic collective member and archivist of the early gay movement. (In the latter, reviewing his dead friend’s orderly files he writes: “The contents crackle and hum and yearn and sigh and weep; they protest and acclaim; they laugh and agonize. They shout. They fall in love. They plot. They think: So much energy spent on thinking and debating and analyzing, but allowing time, always making time, to lick some cute dancer boy’s belly . . . or revel in being called an amazing cocksucker by some blissed-out, lucky neighbour.”)

“Gerald’s work seems to originate from a curious mixture of courage and love”

The work involved in producing an anthology and finalizing his memoir is complicated by the current state of Gerald’s health — he’s dealing with a form of Parkinson’s called Pseudobulbar affect (PBA), a condition that makes it hard, on some days, for him to express himself with his customary fluency, causing this soft-spoken man sometimes to shout, and making him giggle suddenly at surprising moments.

When I spread his various works out, one grabs my attention, giving me a Paradise Lost feeling in light of where we are now politically. It’s a short profile accompanied by photos of Olivia Chow and the late Jack Layton, the then-darlings of the Canadian Left, looking young and vibrant. In the write-up, Layton tells Gerald that their downtown Toronto house was once the vintage clothing store Courage My Love. And Gerald takes that and runs with it: “I can’t help but think that given their frequently unfashionable politics, and given the way they bolster and balance and somehow bless each other, it’s a name that still kind of fits.”

Gerald’s work also seems to originate from a curious mixture of courage and love. What guts and passion it took, after the raids, to be a reporter holding the police to account, and to sit down, years later, with Roy McMurtry and push him to justify his past choices. To document the AIDS crisis even while it was killing off his friends and lovers — an unspeakable task, thankfully taken up by someone with his talents. Pushing that gorgeously written, sex-forward work about Toronto at large is a form of activism — we are here, queer, better get used to it. And now he’s stoically dealing with his latest challenge, PBA, while pushing through my interviews — his intelligence deking around the blocks the condition has put in his way. When, towards the end of our second interview, I ask him about his sex work, he struggles but is able to get this little Geraldian epigram out: “I learned you don’t have to be young, hung and full of cum to do it.”

In the Zena Cherry piece, Gerald recounts how he brought some flowers to the former society columnist, then living in a nursing home, dementia having invaded her once sharp mind. I initially thought of this piece as a bouquet of flowers brought to Gerald on the occasion of his 75th birthday, but I ended up writing something more complicated than that.

I took this piece on partly for selfish reasons, as a refresher course in how to write a profile. What I discovered was deeper than just a set of fancy tricks: some ingenious alliteration here, an amusing parenthetical there. In his profiles, Gerald lets complexity live on the page — and it seems right to do that here. We are seldom just one thing or another. The boy with the floppy hair became a committed gay rights activist, a provocateur intent on pushing hard against what he viewed as social hypocrisy and one of the nation’s most decorated and dearly beloved journalists.

In Gerald’s best work, he gets behind the masks we put on to speak to our actual needs and wants, the things that drive us to become who we are. He wants to find the real stuff, and when he does, he doesn’t look away.

* A note on naming: Everyone calls Gerald by his first name. It would feel both distancing and disrespectful to refer to him as Hannon. So I haven’t done that here.

Legacy: July 13, 2019 10:00 amAn earlier version of this story incorrectly noted that Gerald’s eyes were brown, not blue. The story has been updated.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra