Along highways and atop buildings in Port Louis, Mauritius, billboards featuring lesbian and gay couples and a trans woman ask passersby to end discrimination and hate. On the metro in Kiev, Ukraine, ads with a rainbow-coloured telephone beckon LGBT people who need help and support to call into a free hotline. In San Jose, Costa Rica, police receive sensitivity training for dealing with the LGBT community.

The common thread in these LGBT rights initiatives? All of them received funding from the Canadian government through the Canada Fund for Local Initiatives (CFLI), a $14-million pot of money distributed through Canadian embassies to non-governmental organizations to promote human rights in areas of particular concern to the Canadian government. In the 2014-15 fiscal year, the government chose to include LGBT human rights and inclusion as a priority area for funding.

In all, 44 organizations in at least 34 countries around the world received $886,000 from the Canadian government to promote local projects. The Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development provided Daily Xtra with a partial list of funded projects totalling $686,000, citing the security concerns of some LGBT organizations in refusing to provide the full details.

“Information on some LGBT projects is not released publicly, as the promotion and protection of LGBT rights can be a sensitive issue in certain countries, and we wish to ensure the operational security of the organizations, as well as the safety of the populations they assist,” says department spokesperson Nicolas Doire.

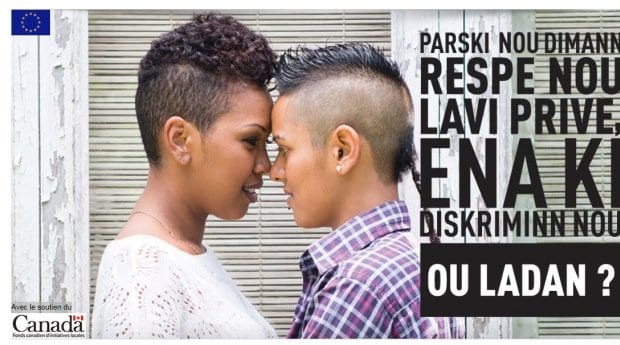

On the small African island nation of Mauritius, a former British and French colony near Madagascar that’s home to 1.2 million people, a CFLI grant helped the country’s fledgling LGBT rights organization, Collectif Arc-en-Ciel (CAEC) launch an awareness and sensitivity campaign about LGBT people.

An attempt in 2011 to update Mauritius’s sexual offences law to remove the sodomy provisions fizzled despite other successful pro-LGBT initiatives, including a ban on workplace discrimination that passed in 2008. Still, the country lacks hate crime laws, and gays routinely face violence and ostracism.

“It is still very difficult for homosexual people to come out because family and social pressures are very strong,” says CAEC coordinator Pauline Verner.

CAEC responded to a call for projects from the Canadian embassy in South Africa and received $19,807 to launch its campaign. The funds went toward purchasing 31 billboards on the island’s main roads, ads in four of the most-read newspapers and radio spots on the two most popular stations, for a month-long campaign in February 2015. CAEC also received money from the European Union to complement the campaign with a web and social media component.

“This was the first Mauritian campaign for LGBT rights. We are very pleased to have been supported by Canada for this project,” Verner says. “The buzz has allowed us to get unprecedented media coverage, and power to bring to the forefront the issues of LGBT rights. For nearly 20 days, we were able to speak freely about the living conditions of people in the LGBT community: discrimination, exclusion, violence, etc.”

The ultimate goals of the campaign are to repeal the sodomy law, create a hate crime law, and intervene in public schools to talk about sexuality and safer sex. Verner says that the campaign sparked some hostile and even threatening reactions from the public, but was an invaluable contribution to the dialogue on LGBT rights.

“Lots of people outside the LGBT community have sent us messages of support and relayed the campaign on social networks,” she says. “But our greatest joy is that this campaign has allowed some people in need to know the CAEC and contact us for help or counselling. The need is real and this campaign also allowed us to make clear to these people that they were not alone.”

In Ukraine, the legal situation is better, but gays and lesbians still face violence and discrimination. The national LGBT organization Gay Alliance Ukraine (GAU) is headquartered in the basement of a nondescript building in Kiev with no exterior signs — for safety.

A $19,971 CFLI grant helped GAU advertise a hotline it had set up to provide information and support to the country’s LGBT people — it was the first such service for LGBT people in Ukraine.

“It’s necessary because we have LGBT organizations only in big cities in Ukraine,” says GAU program officer Valentina Samus. “But if we have calls from a small village deep in Ukraine territory, where he or she is the only gay or lesbian in this area, or they don’t know about any other, and it’s probably a very religious family and city, and they’re nearly [suicidal] because all this oppression, this helpline is a very important support in these cases.”

GAU raised its own funds to start the hotline last fall and applied to the CFLI for money to launch a three-month ad campaign in five cities to promote it over the winter. Call volume increased from 300 calls in January, before the campaign began, to more than 800 in March, the last month for which statistics were available. GAU had to use the grant money to train additional counsellors to support the growth in call volume.

The Canadian money was integral to getting the word out. Although most cities would allow social service advertisements on their public transit systems for free, GAU predicted their applications for free ad space would be rejected.

“If we ask for it for free, I think it would be impossible in Ukraine,” Samus says. “In a few cities [we had ads] that said ‘Hotline for LGBT’ and in small type ‘lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender,’ and they asked us to remove the small type because we can’t write gay on this big board, children will probably see it.”

Despite these setbacks, the LGBT hotline has already helped hundreds of LGBT Ukrainians access information about HIV testing, legal and medical services, counselling and even social and nightlife information. While the Canadian grant has now expired, GAU continues its operations with its own funds and with a new grant from the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency.

At present, it is unclear if the Canadian government intends to continue funding LGBT rights programs through the CFLI. Its inclusion in the 2014–2015 program came under the tenure of former foreign affairs minister John Baird, who resigned from politics earlier this year. His successor, Rob Nicholson, declined to be interviewed for this story.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra