A gay man convicted by a Mexican court of killing his lover is back in Canada trying to rebuild his life.

Dennis Hurley, who was sentenced to 15 years for the death of Toronto landscape architect Murray Haigh, returned to Canada in July 2002 to finish off his sentence after serving five years in a Mexican prison. He was just released this spring to a halfway house. Though he has been keeping a low profile since his return to Canada, Hurley has maintained his innocence throughout.

On Jan 28, 1993, Haigh was found dead in the bathtub of the cottage the couple had rented for the winter in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. A post-mortem indicated he died from blows to the head and drowning. After being questioned by the local authorities, Hurley fled the country. He was arrested two years later and served two years in the West End Detention Centre fighting extradition.

Hurley’s lawyer Frank Addario argued that he was unlikely to receive a fair trial due to “entrenched homophobia” in the Mexican judicial system. Two of Mexico’s leading gay and lesbian organizations expressed similar concerns in writing to the justice minister at that time, Allan Rock. But after appealing up to the Ontario Court Of Appeal, Hurley finally gave up the fight and was returned to Mexican authorities in October of 1997.

Although the campaign to fight his extradition was unsuccessful, it served a purpose nonetheless. “The Mexicans were very aware that I was going down there with a light on them so they couldn’t harm me, because that does happen. I saw that happening in the prison itself. I saw people being beaten and being taken out at night. The whole process before I went was to ensure that that didn’t happen to me.”

Of the conditions laid out at the time of Hurley’s extradition, one was access to a fair trial – something Hurley maintains he didn’t get.

“[The judge believed he] knew I was guilty before everything was done and he said that to me. It wasn’t implied.” Hurley recalls trying to communicate his concerns about the contaminated crime scene and circumstantial nature of the evidence against him. “He said, ‘These are all important points, but we know you did this. We know you’re guilty.’ How do you fight something like that?

“The only thing that was translated for me was if there were questions being asked of me directly or if something was being said by me in English and then the translator would translate it into Spanish. So when all of the experts of prosecution and even the defence experts [spoke], it was all in Spanish so I had no idea what was being said.”

Another condition was that he would be allowed access to Canadian embassy officials. But although there was an honourary Canadian consulate in the town where Hurley was tried, he says that no one from that office was present during his 10-month trial.

“I know that it probablywouldn’t have made a difference anyway,” says Hurley. “But it showed a ‘who cares’ attitude. I was a Canadian in a foreign jurisdiction undergoing stuff that was extremely scary. It would have been scary here, where you understood what was going on. But when you didn’t understand the words or the process – I couldn’t believe they could take such an attitude and leave you alone.

“After I was convicted and after about two years the Canadian government got a little more involved in my case and I started getting people coming up and visiting. But for the first little while there was nothing.”

In some ways, Hurley believes his experience within the Mexican prison system was better than the time he served in Canada.

“Part of that is that I was teaching English,” he says. “You’re just held in such respect because you have a position in the scheme of things…. At first it was just for administration, then for security guards. Eventually I started doing it for the inmates in my own area and then for the inmates in the general area.”

At the same time, the Mexican system doesn’t afford many of the things that Canadian prisoners take for granted.

“For the first three years and eight months I lived in an area where there were six cells, standard six-by-eight…. There was no access to the outside, I had no access to any sort of recreational facilities or even just going outside to see the grass. I was literally inside for that entire time. The only time I got to see the outside was when I had to go see a doctor in a different part of the prison. It was very tough.”

After an unsuccessful bid to get bail within the Mexican system in Jul 2001, Hurley was finally returned to Canada under the Bilateral Transfer Of Offender Treaties in July 2002. “It was really strange because I was viewed as having just come into the system, but I had eight years under my belt.”

Hurley calls the way Canada deals with prisoners transferred from a foreign correction system “a really awful double standard” because Canada accepts the foreign convictions without question, but doesn’t accept reports of good behaviour while in custody. “It seemed so ironic that they would take the bad but not the good.”

Going into his parole hearing last March, Hurley says he had hopes of being transferred to a lower security facility. “Much to everyone’s surprise I was granted day parole and by Mar 14 I was out.

“It was a bit overwhelming. We really went in not expecting it. My institutional parole officer was not supporting my bid for parole because I had no institutional programming and you don’t get parole without it, certainly not with a manslaughter charge. And I also maintained my innocence so I had three major strikes against me. I’d only been in the system in Canada for less than a year so we didn’t expect it to happen and they surprised us.”

Since then, Hurley has been living in a halfway house. His next hearing is set for Sep 3 and he’s optimistic he’ll get full parole at that time.

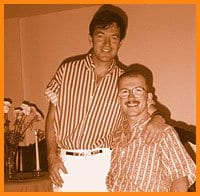

Hurley, who recently celebrated his 40th birthday, is now focussing on his relationship with his new partner and on the business that they’re opening together. He says that his experience has taught him to take each day as it comes.

“If somebody looked at me in early March and said in the next six months I could be out, I would have been as incredulous as if someone had said to me before all this began that all this was going to happen…. I wouldn’t have dared to dream of having as good a life as I have now. I certainly never thought I would find someone who would go out with me. There’s definitely not a line-up around the corner for someone willing to date someone convicted of killing his last lover.”

And although he hasn’t given up on the possibility of attempting to have his conviction overturned, he says it’s not something he’s ready to take on just yet.

“Are they ever going to say they were wrong and does it really matter to me? Plus it opens up a whole can of worms of what happened to Murray. It’s all behind me now and perhaps that sounds cruel, but whatever happened to my partner is no longer a part of my life. I know it didn’t involve me and I have to let it go. We’re talking 1993, 10 years ago that he died. The opportunity to find out what really happened has long passed. I’ve had to move on for my own survival.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra