Herb Spiers (right) with his lover Ray Gray in New York in the early 1980s. Credit: Gerald Hannon

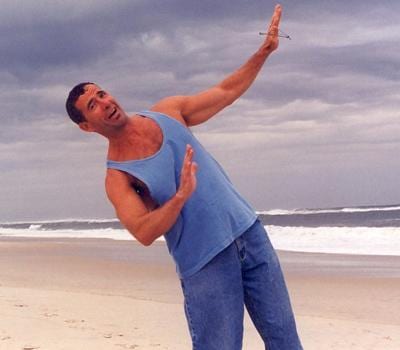

Herb Spiers seen in 1996 at Fire Island. Credit: Gerald Hannon

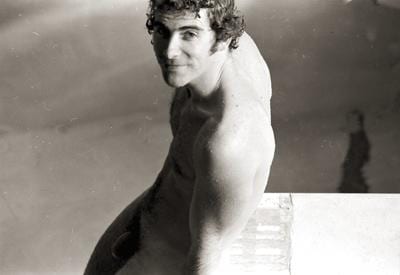

Spiers in the pool at the YMCA at Broadview and Gerrard in Toronto in the 1970s. Credit: Gerald Hannon

It was easy to fall in love with Herb Spiers. I did. So did many others.

That was back in the 1970s in Toronto, when gay liberation was young, brash and in your face, and Herb seemed the perfect embodiment of all those qualities. He would have been in his mid-to-late 20s, handsome, a Midwest boy minus the aw-shucks manner, his light brown hair curly and fashionably ’fro-ish, his manner forward, confident, funny and striving. He was American, and even though he was from the not-exactly-glamorous Columbus, Ohio, that touch of exoticism added to his allure.

In Toronto to work on his PhD in education at U of T, he was one of several Americans, like Jearld Moldenhauer, Michael Lynch and Rick Bébout, who made significant contributions to the gay rights movement in Canada. You can watch Herb, big hair and all, holding forth on Yonge St on Halloween in 1973 about seven minutes into this CBC Digital Archives clip. Pelting drag queens with eggs was good Toronto sport in those days. Herb, a founding member of the early activist group Toronto Gay Action, was on the scene to protest its barbarity. It’s no surprise the CBC cameras focused in on him. He had presence. He had smarts. He gave good sound-bite.

He was also the co-author of one of the most significant pieces of writing in Canadian gay history. It was called We Demand and was presented to the federal government in August, 1971. On August 28, more than 100 gays and lesbians rallied on Parliament Hill to support it. It was the first public demonstration of its kind in Canada, and it seemed to be asking for the moon: a uniform age of consent, the right to serve in the armed forces, and the removal of archaic homophobic laws from the Criminal Code. We Demand set the agenda for Canadian gay activism for the next decade. He wrote it, and the rest of us would, eventually and to our astonishment, win almost everything he demanded.

He and I and three or four others lived together for much of the ’70s. We’d rent a house and share expenses based on income – we wanted to live the revolution! Our first group bank account bore the name “A Half Dozen of the Other.” We were all involved with The Body Politic, the pioneering gay publication that gave birth to Xtra. Herb wrote for it, and stripped naked for it when required (we published the photos). He liked taking his clothes off and liked showing his dick. A dinner guest remembers him bringing a container of ice cream into the living room, whipping his dick out, rubbing it in the ice cream and trying to get us to eat off it. For a time, no drunken party was complete without someone demanding to see Herb’s dick, a wish that never went ungranted.

Sometime in the mid-to-late ’70s, he moved to New York. He started off working in sales in a dildo store but before long became partners in an art agency and publishing company. He fell in love with interior designer Ray Gray, moved into a 4,000-square-foot loft near Union Square (Ray owned the building – Herb got the second floor; Ray the eighth), and lived a pre-AIDS New York gay life the likes of which may never be seen again. Herb became a gym rat, got pecs, got abs, got biceps. He was hot, he had money and he shared it. When you visited him in New York, and many did, he took you everywhere, and he picked up the tab.

He was a regular at the famous discos of the period: Flamingo, The Saint. A friend of acclaimed novelist Ed White, he would become the inspiration for “The Oracle,” one of White’s best-known short stories. Every summer, Herb and friends rented impossibly glamorous summer houses on Fire Island. Sometimes they flew there from Manhattan. I joined them once, stepping out of the small sea plane into a gentle surf sliding up onto a beach bristling with porn-ready bodies.

Another Toronto friend remembers him at one of Fire Island’s famous parties, hosted in July 1979 by Canadian architect Arthur Erickson and his partner Francisco Kripacz in their beach house, a residence so huge and extravagant it was known (half enviously and half scathingly) as Lincoln Center. Herb was one of its lusted-after muscle boys, the centre of a world of beautiful men when, late, late into the night, the roof opened up, releasing hundreds of gold and silver balloons to float out over the water as disco diva France Joli took to the stage and belted out “Come to Me,” the song that would become that year’s hit.

Then AIDS happened. Ray, Herb’s lover, was among the early deaths. Eventually, all of his New York friends died. It happened that way then; you had a lot of friends, and then you had none. And then, if you were Herb, you wept, dried your eyes, started afresh and created a circle of intimates that would eventually include Joe Daniel, his partner of the last nine years. Herb reclaimed himself as an activist (he was also asymptomatically HIV-positive), becoming involved with the city’s Gay Men’s Health Crisis. In 1987, he became a founding member of ACT UP, the most vocal and active of the American organizations that fought for the lives of gay men in those years. In an echo of We Demand, he collaborated in 1989 with Toronto’s AIDS Action Now to write, for the International AIDS conference, what came to be known as the Montreal Manifesto: “The Declaration of Universal Rights and Needs of People Living with HIV Disease.”

Over the years, HIV slowly caught up with him. Technically, he died of cancer, but his health had been much eroded over the last decade of his life by the virus. He also suffered from what I think of as The American Disease: he wanted to be a celebrity. Not just any celebrity: he wanted to be a famous writer. He wrote charming, quirky, eccentric letters to his friends, but what he wrote for the world was probably unpublishable.

He laboured for years on a children’s book chronicling the adventures of Fifi, a French mouse. It mirrored his sunny good nature but drew out the narrative at a length unlikely to engage the attention of the school audience he had in mind. You loved him for never giving up on that dream, but you always wanted him to realize that the best sentence he ever wrote was undoubtedly the shortest. It was addressed to the federal government. It read: We Demand.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra