Though controversies over using the singular “they” as a gender-neutral pronoun rage on, it should be recognized that English is still much less gendered than most languages. It’s also more inclusive and flexible by design: English easily absorbs words from other tongues and is constantly reinventing its own. Throw an “ing” on practically any noun and, bam, you have a verb! And while the use of the singular “they” can be traced back to the 14th century, many other languages are without this sort of historical option, necessitating a search for new words to express gender neutrality. Hebrew speakers are creating gender-neutral pronouns, some Spanish speakers replace the male-gendered suffix “o” and the female-gendered suffix “a” with “x” or “@” (giving us words like Latinx and Chican@), while Sweden added the gender-neutral pronoun hen to the Swedish Academy Dictionary in 2015.

In my home province of Quebec, like all matters linguistic, adopting inclusive language is a tad more complicated. If you know anything about French, you get that it’s an inherently gendered language in which verb conjugations depend on the pronoun and every noun is either masculine or feminine, leading us to essentially call things Mr. Wine or Ms. Table. You might also know that French defaults to masculine, so if you’re referring to a group of 10 people, nine of whom are women with just one guy hanging out, the pronoun to designate them defaults to the male ils.

In recent years, some publications have opted to feminize their content for greater equality, like the Université du Québec à Montréal’s newspaper Montréal Campus did in 2019. Now, for example, when the paper is writing about professionals, they’ll make it inclusive by spelling it professionnel(le)s, and they no longer default to masculine. Around the same time, an anonymous group also published a guide for LGBTQ2 usage within the school, calling for greater awareness and support of gender-neutral and inclusive language by professors and students alike, proposing alternatives that involve using dots in conjugated words in order to reflect many genders (like professeur·e·s and étudiant·e·s). With gender so enmeshed in the language’s structure, it’s naturally more of a struggle for French speakers to embrace new gender-neutral options.

In Quebec, iel, a contraction of the male and female pronouns il and elle, is a common choice for non-binary and gender non-conforming people. Definitive articles like le and la (both meaning “the”) have alternatives like lae, lo, li and lu, but are not as widely used. Instead, the dominant idea is to create gender-neutral sentences, like changing la fille (the girl) to l’enfant (the child). That means Mr. Wine or Ms. Table are sticking around.

Gender-neutral language versus the French love of officialdom

New words or constructions are one thing, but French culture is altogether another. The French have a passion for officialdom. Whether it’s the names of your favourite cheese and bubbly wine or what words constitute correct French, there’s a council or academy for that. The Académie française, France’s ruling body that gets to select which words are correct French, is notorious for its gatekeeping. In Quebec, we have the slightly more lenient Office québécois de la langue française (because we love a long acronym almost as much as we love Céline and all-dressed pizza, we know it as the OQLF). In 2018, the OQLF officially added a page about designations for non-binary people, detailing pronouns like iel and nouns like froeur to replace frère and soeur (brother and sister), as well as promoting gender-neutral usage.

Marie-Pier Boisvert, the general director of the Conseil québécois LGBT in Montreal, Quebec’s main organization for defending queer and trans rights, appreciates the flexibility of the OQLF’s online resource. “Unlike with a traditional dictionary that’s final after being printed, [the OQLF] is constantly changing and is a lot less rigid than the Académie française,” she says. That sentiment, however, isn’t shared by all: Some would want to lock up the French language like a princess in a tower and throw away the key. In a November 2019 article in the Journal de Montréal, journalist and media personality Denise Bombardier called out the so-called “LGBTQ+ lobby” and accused the OQLF’s linguists, who put together the page’s information about degendering French, of essentially “destroying its genius, its beauty and its capacity to define reality.”

Of course Bombardier doesn’t care whose reality is being defined—certainly not the everyday lives of people who feel excluded by their own mother tongue. Shortly after the publication of Bombardier’s article, the OQLF modified its page about non-binary designations and significantly reduced its explanation of gender-neutral language use. Though the page still mentions iel and froeur, it added a framed section of bolded text stating that the OQLF does not recommend using the new terms in common writing practices. As Séré Beauchesne Lévesque, co-founder of the Groupe d’action trans de l’Université de Sherbrooke, puts it, the retraction was equivalent to being told that non-binary people don’t exist. “Our visibility is being destroyed and willfully censored,” Beauchesne Lévesque says. “The transphobic lobby is actually the one winning against us. A single person publishes this opinion and that pushes a governmental organization that’s supposed to represent the population as a whole to stop using these words.”

Over the decades, Bombardier has been an outspoken defender of French, which she showcased in her Journal de Montréal article by mentioning that the OQLF was created to “preserve French in the face of an English invasion.” In Quebec, surrounded on all sides by English-speaking regions, fear of losing French has led to a lot of ink being spilled about the need to bolster and preserve the language. While understandable, that fear can prevent the language from officially keeping up with how people use it in their everyday lives. “People accuse us of wanting to destroy the French language,” says Conseil québécois LGBT’s Marie-Pier Boisvert. “They don’t seem to get that it’s actually the opposite. The reason we’re trying to create our own terms is because we want to stop using English ones and make French more inclusive.” A lot of language about gender and sexual diversity has originated from the English because Francophone Quebecers have found in it words that fit their identities. A quick search of agenre, a translation of “agender,” in the French dictionary Larousse yields no results, whereas Merriam Webster has a page devoted to the term with its usage traced back to 2006.

This fear of creeping English is also the motivation behind the OQLF jumping to create French equivalents for commonly used English terms. Instead of “selfie,” for example, a word that quickly spread everywhere on social media and in our parlance, Quebecers were told that “égoportrait” was the proper word. I recently spoke about officially formailzing languages with Conseil québécois LGBT’s Lou Tajeddine, who is developing a guide for media and other organizations about language usage for trans and non-binary people. When we talked about official resistance toward gender-neutral pronouns, they pointed out that the OQLF has focused on much less important terms (that’s you, égoportrait). “It’s not that we can’t invent new terms, it’s that these pronouns aren’t used by enough people for there to be pressure for them to get translated,” Tajeddine says. “We’re trying to apply that pressure.”

Despite these roadblocks, Beauchesne Lévesque feels that the fight for inclusiveness in the province is finally gaining some ground. Their group, founded in 2016, made some headway last fall when Université de Sherbrooke became the first university in Quebec to allow students and employees to use a name other than the one that appears on their legal documents and to offer autre (other) along with “male” and “female” as a gender option for all university communications. (And a non-gendered locker room is planned for the spring.) Though this is a win for gender diversity, it’s also not the one that Beauchesne Lévesque is ultimately striving toward—they were hoping for something more affirmative, like “non-binary.” Instead, the option the university chose leaves Beauchesne Lévesque feeling like their school would prefer to opt out of gendering people altogether rather than gendering them correctly. According to them, the conversation needs to steer toward true inclusion, which is intrinsically rooted in language. “As a non-binary person, if I wear a dress or something more masculine, I’m automatically categorized. Language is often the only thing we have to make progress with, so it’s extremely important to respect it,” Beauchesne Lévesque says. However, they also feel like there can be instances when speaking such a gendered language is actually a positive experience. “I like that in some circumstances French emphasizes gender, because it allows us to highlight our gender however we like, whereas in English, it can be difficult to do so since everything is non-gendered from the get-go,” Beauchesne Lévesque says. “If you say that you’re heureuse (happy), you’re affirming that you’re a woman and that you prefer female pronouns, and if you say that you’re heureuxe, you’re affirming that you’re non-binary.”

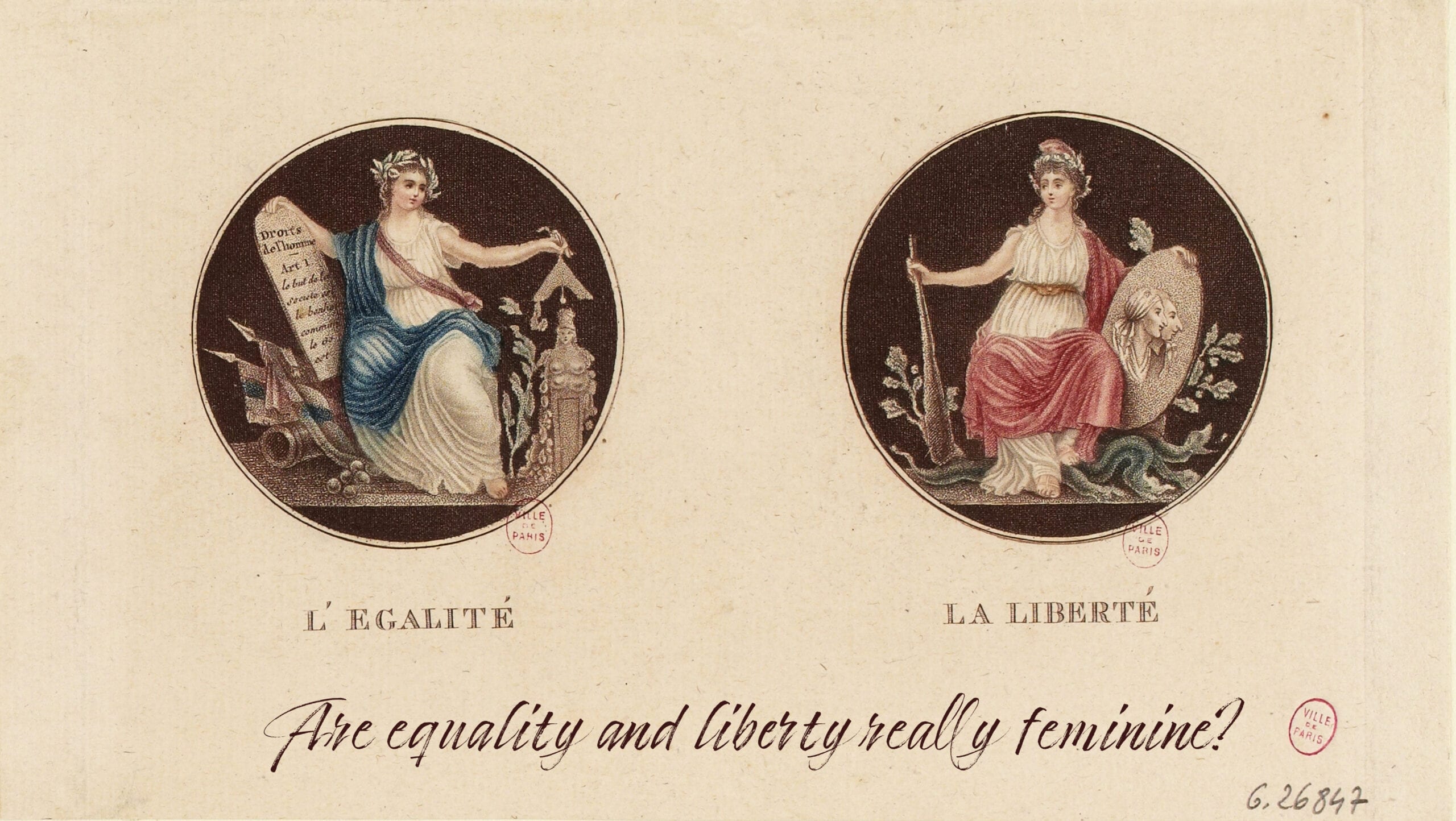

It would certainly be a positive step if linguistic bodies like the Académie française and the OQLF gave their seals of approval, but now it’s up to everyone to make their daily usage, as well as their headspace, fit to print. Going all the way back to France’s national motto from the French Revolution—Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité—we’re faced with the language’s built-in contradictions. Beyond the noun fraternité (fraternity) being, ironically, feminine, it’s also inherently male-centric, highlighting the ingrained practice of defaulting to masculine, even in a call to unity meant to rouse all hearts. Liberty and equality do come first here linguistically, but we’re going to have to push harder for that to be reflected in the culture as well.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra