Wade Davis now speaks about queer issues on behalf of President Barack Obama.

Wade Davis made international headlines last summer when he spoke publicly about what it was like to be closeted in the National Football League. The news was tough on his parents.

“I grew up in the South and my family is very religious,” says the Louisiana-born Davis, who began his professional football career after attending Weber State University in Utah. “Thankfully, my mother has come full circle. She used to be very much against [homosexuality], whereas my father still refers to it as a ‘lifestyle choice.’ To be honest, my father and I are still not in a good place. But it took me 15 years to be okay with being gay, so I feel I need to give them time as well.”

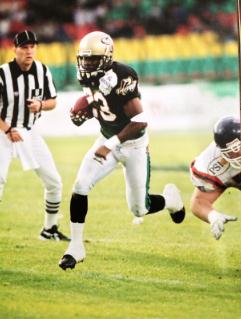

Davis is a former NFL defensive back who – while he never cracked a 53-man roster in his NFL career – was signed as a free agent by the Tennessee Titans and played in the pre-season for the Washington Redskins and the Seattle Seahawks before moving on to NFL Europe, where he played for the Barcelona Dragons and the Berlin Thunder.

On March 2, Davis will close Montreal’s fifth annual Afro-Caribbean gay and lesbian film festival, Massimadi, with a free public lecture at the Imperial Theatre in which he will speak about how he worked hard to maintain his “straight” cover in the NFL.

“In my football days I was one of the guys. I was very well liked, so I had this persona to keep up,” Davis says. “I’d even go to strip clubs with the team to keep up my image of being a strong, heterosexual, masculine man. I remember spending my [entire first paycheque] in a strip club trying to act like one of the guys.”

Davis says his NFL closet took a psychic toll.

“You’re always tired – not physically, but mentally,” Davis says. “You are limited by what’s going on in your head. You’re two different people: [in public] you are the person you think the world wants to see, and when no one’s around you’re you. Pushing that real you away, hiding it in a safe place so no one will find out about it, that’s the most exhausting part.”

Davis’s NFL career ended in 2003, and today he is the assistant director of job readiness at the Hetrick-Martin Institute in New York City, where he teaches life skills to gay youth.

In February Davis also joined the advisory board of You Can Play, the organization co-founded by Patrick Burke (son of former Maple Leafs GM Brian Burke, who also sits on the board) that is dedicated to eliminating homophobia in sports.

Says Davis, “When Patrick asked me join the board, I wanted to be sure I was still working on the ground, and to meet someone with the same drive and focus as myself was a blessing. Patrick is brutally honest and knows there is a lot of work still to be done to get rid of homophobia in sports.”

But the times they are a-changing: the NFL this week said it will investigate improper questioning by team representatives about the sexual orientation of collegiate players at the NFL Scouting Combine in Indianapolis. University of Colorado tight end Nick Kasa told ESPN, “[Teams] ask you [questions] like, ‘Do you have a girlfriend?’ ‘Are you married?’ ‘Do you like girls?’ Those kinds of things.”

The pressure now on a gay NFL player to come out – in essence, to become the “gay Jackie Robinson” – has never been higher.

“I think that first pro player who comes out while he’s still playing is going to be extremely powerful,” adds Davis, who believes that first out gay athlete will be an NHL star. “But that player needs to be ready, not just for all the great things that will happen, but also for all the negative reactions, especially [on the internet]. He will become the face of this movement and will inevitably influence the lives of so many gay youth about what it means to be a man. I [also] think his coming out has to be for the right reasons, not because he wants to become this gay icon.”

Davis also believes real change will be made not by the gay Jackie Robinsons of the sports world, but by heterosexual players like Baltimore Ravens linebacker Brendon Ayanbadejo, who has been very outspoken about his support of gay civil rights.

“We need more straight allies,” says Davis, who also speaks about queer issues on behalf of President Barack Obama. “I think [when it comes to combating homophobia] that will be more powerful than any gay athlete coming out. So for me, the question is not when will a gay athlete come out, but when will big-time baseball, football, basketball and hockey players come out and say, ‘I’m against homophobia and I want all straight people to join me against this.’ That’s when real change will come.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra