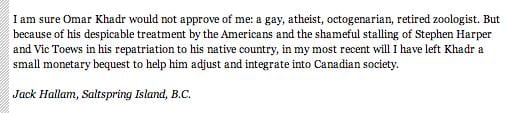

The letter Jack Hallam wrote to MacLean's announcing his plan to leave Omar Khadr money in his will. Credit: Andrea Houston

For Jack Hallam, leaving $700 in his will for Omar Khadr is both a kind gesture and a commentary on his “abominable” treatment by governments.

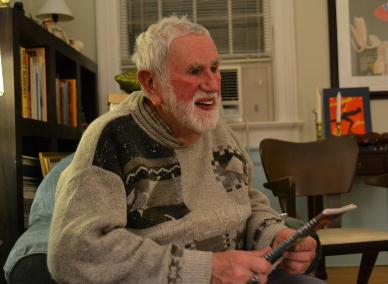

The 84-year-old gay man, a retired zoologist who now lives on Salt Spring Island in British Columbia, says he was moved by Khadr’s story.

“He’s been treated so abominably and despicably by both the American and Canadian governments. I’m not sure if he ever threw that grenade,” he says. “I don’t believe he’s a terrorist or a war criminal. He was an enemy combatant, but he was only 15. He was also brainwashed by his father.”

He suggests that the queer community should offer support for Khadr, now 26, perhaps at the 2013 Toronto Pride parade.

“Next Pride, a group of people should wear rainbow-coloured niqabs. Maybe with a bare ass at the back,” he adds with a devious giggle.

In October 2010, Khadr, who was born in Toronto, pleaded guilty before a military commission to five war crimes, including murder in violation of the rules of war. He was sentenced to another eight years behind bars but was allowed to return to Canada to serve out the rest of his sentence. He was brought back to Canada in September.

Hallam thought Khadr could put the money toward his education now that he’s been repatriated to Canada after spending a decade at a US military prison in Guantanamo Bay.

“When he gets out, he should come live with me,” he offers, very seriously. “I’d love to learn more about him.”

Hallam says he was a little surprised by all the attention he received after his letter, in which he announces the newly added bequest in his will, ran in Maclean’s. There were some hostile and aggressive comments, but they were mostly online, he says.

A proud atheist, Hallam shrugs at those who question whether Khadr, a devout Muslim, would approve. He wants to use the moment in the spotlight to highlight queer causes that he feels passionate about.

“I want to talk about Queers Against Israeli Apartheid,” he says. “I think there should be more such groups. What about Queers for First Nations or Queers Against Animal Cruelty, Abuse and Neglect.”

The life-long animal lover was recently in Toronto to deliver another gift, a box brimming with papers, photos, newspaper clippings and other documents for the Canadian Lesbian and Gay Archives. As he pulled out examples, stories usually came with them.

Hallam was thrust into activism after he was charged in 1970 with committing an indecent act. “It happened in the washroom of the CNE coliseum,” he says.

His arrest came one year after homosexuality was made legal, but police used other laws to attack gay people. Hallam’s lawyer was a young Clayton Ruby.

The case took a turn when one of the arresting officers testified in court that Hallam is circumcised. “But I’m not! So, these 8-by-10 glossy photos were handed around to the all-male jury.”

He was acquitted.

“I wonder how long they keep photographs in the file?” he wonders. “Maybe I should email them and get them to turn those photos over to the archives. I was in better shape back then,” he jokes.

A long-time philanthropist, Hallam is responsible for two human rights awards at Gulf Islands Secondary School, the endowment of two entrance bursaries for needy First Nations students at Lakehead University, and two animal rights awards at Brock University. He also donated $100,000 to the Mark S Bonham Centre for Sexual Diversity Studies to support the creation of two scholarships.

He is a member of the Salt Spring chapter of Dying with Dignity and the BC-based Farewell Foundation for the Right to Die.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra