“It may be long before the law of love will be

recognized in international affairs. The machineries of government stand

between and hide the hearts of one people from those of another.”

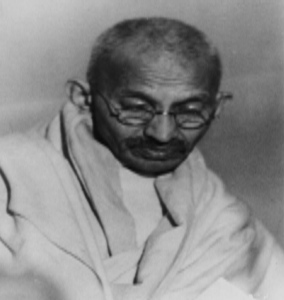

Gandhi couldn’t have said it better himself. And he

didn’t have to. They’re his words, which the Indian state of Gujarat and other

states would do well to live by as they indulge in collective handwringing

about banning Great Soul, a new biography that reveals the Mahatma’s

relationship with another man in South Africa in the early 20th century.

In Great Soul, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Joseph

Lelyveld quotes the content of letters between Gandhi and German-Jewish

architect Hermann Kallenbach who once shared a home together in South Africa,

where they worked on the non-violent human rights struggle there.

In an April 7 email blast, UK gay rights activist Peter

Tatchell excerpted some of the loving language Gandhi penned to Kallenbach:

“Your portrait (the only one) stands on my

mantelpiece in my bedroom,” Gandhi wrote. “The mantelpiece is

opposite to the bed.”

He added: “How completely you have taken possession

of my body. This is slavery with a vengeance.”

Gandhi asked Hermann to promise not to “look

lustfully upon any woman.” The two men pledged “more love, and yet

more love… (such as) the world has not yet seen.”

As critics of the revelations carp about the

“insult” to the Mahatma’s memory and the whole Indian nation,

Gandhi’s great grandson Tushar Gandhi sought to introduce some sanity into the

faux-controversy.

“How does it matter if the Mahatma was straight, gay

or bisexual?” Tushar asks. “Every time he would still be the man who

led India to freedom.”

From Tatchell: “His sexuality does not diminish his

political achievements or his character one iota. Only a homophobe would take

offence at the evidence that Gandhi had a same-sex relationship.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra