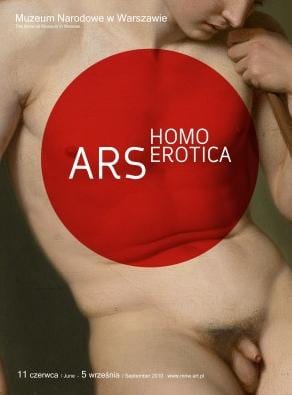

Pawel Leszkowicz was the curator of Ars Homo Erotica in Warsaw.

While 22 of the 51 countries in Europe recognize same-sex marriage or partnerships, Poland is not one of them.

However, queer curatorial practices are changing the country’s cultural landscape — and not just in the art world.

In a lecture at the Ontario College of Art and Design on Feb 16, Pawel Leszkowicz, a Polish art historian, lecturer and curator, highlighted queer curatorial practices — seeking out gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender content in museum collections and displaying it — as a way to oppose the marginalization of queer-themed art and, by extension, queer people.

“One aspect of my approach to queer curating [is] the political impact of queer curating, art and representation as opposition against dominant narratives, especially the strait-jacketed national constructions of identity and visuality based on exclusions,” Leszkowicz said.

In 2010, Leszkowicz curated Ars Homo Erotica, an exhibition of transnational queer art, at the National Museum in Warsaw. The exhibition, which was the first of its kind in Eastern Europe, featured 300 pieces of art, from antiquity to the 21st-century, that Leszkowicz searched for in the museum collection and in the contemporary art milieu.

The pieces were organized thematically into sections such as “Time of Struggle,” “Lesbian Imaginarium,” “Transgender” and “Homoerotic Classicism.”

“My goal was not only to find homoerotic pieces in the collection of the museum, but to combine them with contemporary queer art from Central and Eastern Europe, because we wanted to use the exhibition to speak not only about the homoerotic pieces in the collection, but also about the question of queer rights where these questions are very polarizing and topical,” Leszkowicz told Xtra.

Leszkowicz says he has been interested in queer art throughout his career.

“Of course, this is on the one hand personal and connects to my identity of being queer, but I also noticed in many countries these kinds of visual tradition are suppressed, are hidden, are not on the surface of cultural space,” he says.

Leszkowicz’s partner of 17 years, Tomasz Kitlinski, says such art activism is especially important in today’s Poland.

“We tried to combine academic research, art and activism as one, because we really need to oppose homophobia in Poland, which, although lessening right now, is still quite strong,” says Kitlinski, who works closely with Leszkowicz on projects such as the exhibition and their book Love and Democracy.

The exhibition, which was visited by 45,000 people, has been called a revolution.

“Queering the museum is a work of discovery, like a thriller, like a detective novel, to trace this ‘love that dare not speak its name.’ There are so many representations of same-sex love, as it turns out; it just takes some effort to discover them. It’s a major work of sublimation, of discovery, of cultural work for the LGBT community in Poland,” Kitlinski says.

“There were so many prejudices against [queer Polish people], and suddenly we are featured in the National Museum. It changed our cultural status, and it contributed enormously to the lessening of homophobia. This exhibition was a breakthrough in LGBT cultural life in our country.”

While homosexuality has never been illegal under Polish law (a fact that was formally codified as early as 1932, when the age of consent for both heterosexual and same-sex sex was set at 15), there is not yet any legal recognition for same-sex couples. However, homophobia is rampant in the country, and in 2007 the European Parliament called on Polish politicians to stop inciting violence against gay people.

“We cannot hope for even the recognition of partnerships in the near future because of the opposition of the Catholic Church and of the politicians,” says Jerzy Krzyszpien, a long-time gay activist who is a linguistics professor and the translator of several gay- and lesbian-related texts. But while Krzyszpien is not hopeful about the immediate future, he does see progressive opinions in many of his students.

“Opinions change, and some of the younger generations are more open-minded,” he says.

Overall, the landscape is starting to improve. In October 2011, Anna Grodzka and Robert Biedron became respectively the first known transgender woman and openly gay man elected to the Polish parliament. Both are members of Palikot’s Movement, a progressive party that supports gay rights and abortion, among other liberal causes.

Queer culture in Poland is also thriving.

“In spite of repressions under the far-right government [of 2005], the scene is just effervescent,” Kitlinski says. “The culture — painting, installation art, performance art, theatre, literature — is in full swing, and we have excellent lesbian and gay writers, visual artists, cultural critics. What we are lacking is legal recognition of same-sex partnerships; then our love could be celebrated and sanctioned, and we really are looking forward to it.”

Below is a video interview with Pawel Leszkowicz that was done during the exhibit in Poland.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra