Jamaican queer activist Gareth Henry was friends with 13 people murdered since 2004 just because they were gay. The bodies of three of them have never been found.

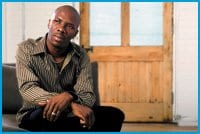

So it’s not surprising that Henry — until recently the cochair of the Jamaica Forum for Lesbians, Allsexuals and Gays (JFLAG) and now a refugee claimant in Canada — breaks down when talking about the death of his coworker and one-time roommate Steve Harvey in 2005.

“It was a Tuesday night,” he says. “We finished a meeting about 11 o’clock. We went our separate ways. I was called at about two in the night and told Steve was brought home by four men and the four men said to his housemates and his partner, ‘We’re going to kill Steve because he’s gay.’ They left with Steve. When I heard what was said, I said, ‘That’s one more of my friends who’s been murdered.’ Honestly speaking, there was no way I had the slightest hope he would be alive. The only thing I hoped was when they kill him that they leave his body in a place where we can find it, have a funeral and remember him.

“In the morning, it was the day before World AIDS Day, I was working on the case of a young man who had been beaten at his school by students and some teachers for being gay. I got a call that a body was found. I went and it was Steve. I was asked to identify the body because I was a friend. I broke down, I was crying. It was real bad to see a friend like that.

“The police officer says, ‘You must be a batty man. Why is a man crying over another man? That’s why Jamaica is the way it is, because you’re so nasty.’

“The next day it was World AIDS Day, I was woken up in the morning. It was three police officers pointing to my window, saying ‘Batty man, JFLAG man, we don’t want him around here.'”

Henry, 30, continued to endure threats, harassment and beatings — often from police — until November, 2007, when he received another threat near his new home, a gated community with 24-hour security.

“I was stopped in traffic when a man got out of his car and came over to me and said, ‘Gareth, we know who you are and we’re going to kill you and burn JFLAG down.’I was really devastated by that threat,” he says.

“I went for the very first time to live with my partner. But I didn’t want to get him in trouble so I was basically living in solitary confinement. I was living in fear. I was being totally crippled by fear. If I heard someone on the outside I could not sleep. I said to myself, ‘Nobody should live this way. I’m not in prison. I need to break free.’ I had exhausted all possible options.

“I came to Canada on Jan 26, basically fleeing for my life.”

***

Henry had already accepted an invitation to be this year’s international grand marshal for Toronto Pride, although he hadn’t been planning to come to the city until June. But once here he wasted little time continuing his campaign for queer rights in Jamaica.

On Valentine’s Day of this year, Henry — with Pride, Egale Canada and the Metropolitan Community Church of Toronto — launched the Call for Love campaign. The campaign, mirrored by similar ones around the world, calls for the protection of queers in Jamaica.

The launch included delivering a wreath to the Jamaican consulate in memory of the island’s murdered queers. Henry also delivered a letter to the consulate asking the Jamaican government to ensure police “uphold their sworn duty to equally protect and serve all Jamaican citizens.” The day was selected because it was the first anniversary of Henry nearly being beaten to death by a mob in Kingston.

“For the first time ever I was into doing something for Valentine’s Day,” Henry recalls. “My partner is into Valentine’s. I went into a pharmacy. I saw three guys [from JFLAG] coming in with a woman behind them cursing and saying some really dirty things about gays and batty men, how they’re dirty and must be killed.”

The pharmacy staff, observing a gathering crowd outside, called the police and barricaded the store with Henry and his three friends inside. The first police unit to arrive said they couldn’t help and left.

“The second unit arrived, saying we were nasty and the people have a right wanting to beat us,” Henry says. “They said they can’t help us right now, they have to call for backup. By this time there’s over 200 people outside. So I got on my cell phone and called Rebecca Schleifer of Human Rights Watch. I found out later she had called the police commissioner.

“Finally seven police officers arrived and were very rude, saying we shouldn’t be flaunting our sexuality in front of people. I said, ‘Sir, this isn’t the way you should be talking to us.’ One police officer slapped me in the face. Another one hit me in the back of the head. They started hitting me all over, calling me batty man. They were dragging me, started hitting me again.”

Henry says he resisted being dragged outside because of the memory of what happened to a friend on Sept 24, 2004.

“I remembered immediately Victor Jarrett, who was a friend of mine. I was standing about 80 metres away from Victor when he was being beaten by three police officers and an angry mob gathered and said to the police officers, ‘Hand him over, let us finish him.’ The police officers did throw him to the crowd who beat Victor and chased him through the town. The following morning it was headlined in the local paper, ‘Alleged homosexual chased, beaten, chopped and killed.’

“So I was resisting because this picture was so vivid in my mind. The police started hitting me more, then one of the police officers used his gun and hit me in the abdomen and I was in severe pain. Then they walked off.”

Henry says the staff of the pharmacy eventually helped the four men slip out of the store and into a car outside.

***

Mob attacks on gay men in Jamaica are common, Henry says. He almost breaks down again while remembering the death of Nokia Cowan, soon after Harvey’s murder.

“Nokia was going about his business,” Henry says. “Someone said, ‘He walks like a gay man.’ His only options were to be beaten by hundreds of people or jump into the harbour. He jumped. He couldn’t swim. The crowd watched him gasping for breath. When he disappeared under the water, that’s when the mob walked away.”

Most recently according to Human Rights Watch, on Jan 29, a mob broke into the home of four gay men. Three ended up in hospital, one with severe wounds from a machete. The fourth man, still missing and presumed dead, is thought to have jumped off a cliff to escape the mob.

Nor are lesbians immune from attacks. Henry tells of two women he knew who were murdered in their home in 2006 and buried in a pit behind the house.

Henry says none of the perpetrators in any of these cases have ever been brought to justice.

Schleifer, with Human Rights Watch’s HIV/AIDS and Human Rights Program, says she is convinced it would have been just a matter of time before Henry was added to the list.

“I’ve been fearful for Gareth’s safety for years,” she says. “I came across the condolence card I wrote to JFLAG after Steve’s murder. It made me cry but it also chilled me. I was so scared I would have to write a note like that for Gareth. I was deeply relieved that he was gone. But it’s also sad. Nobody should be forced to leave their home like that.”

Henry says that even with the danger he faced he wouldn’t have left if he hadn’t had a successor at JFLAG. But given that Henry has been with JFLAG from its start 10 years ago, he knows the change won’t be easy for the organization.

“I had just turned 20,” he says of JFLAG’s beginning. “I was just doing basic administrative stuff and I fell in love with JFLAG.

“In 2004 Brian Williamson, who was the face of JFLAG, was murdered. When I went to his house people were celebrating, saying, ‘We’re going to get them one by one.’ When I looked at what happened to Brian, I thought JFLAG was the right thing to be doing. I was asked to be the program manager and cochair. With my involvement in JFLAG at that level I really understood the magnitude of the homophobia.”

The reality in Jamica, he says, is that homophobia is so deeply entrenched because the establishment — politicians, religious leaders, media, police and entertainers — all encourage it. All have fought against repealing Jamaica’s antisodomy law, for example. The law can send men convicted of anal sex to jail for up to 10 years.

“The church in particular, its stance is we need to be healed and the law should not be removed from the books,” he says. “Ministers preach hate and damnation from the pulpit and they go public with their views. Jamaica is deemed to be a very Christian country, hence religion plays an integral part in our politics.”

Henry points to a proposed bill of rights that has been under discussion in Jamaica for years. The bill would take away the right of police to enter a home without a warrant.

“The church responds to this by saying it needs to exclude situations with gays and lesbians,” Henry says. “Gays and lesbians can’t be allowed to have privacy in their homes because gay men in particular are breaking the law.”

And yet even gay men in Jamaica yearn for religion. Schleifer says she was amazed to hear from queers in Jamaica about their need for an organized church.

“One of the really stunning things I heard was gay men telling me, ‘I can’t go to church any more. When I go, I visit. I go from church to church where nobody knows me,'” she says. “I’ve talked to hundreds of people around the world about the abuses they’ve faced and none have ever said anything like that.”

Henry himself founded a branch of the Metropolitan Community Church in Jamaica. Although, given conditions for queers in the country, the church has no actual building.

“We have created for ourselves a safe space for the community to worship,” he says. “I reached out to the MCC at the end of 2005. We can’t have a physical location which is public knowledge. But there are a lot of gays and lesbians who have suffered from the message from the pulpit and need a space where they can reconfirm to themselves that they are gays and some kind of spiritual beings.”

Henry says that the media in Jamaica further fans the fires of homophobia. When JFLAG has tried to run public campaigns against violence, the group has been unable to find a single media outlet in the country to run their ads. But he says the media continues to celebrate homophobic musicians.

Music in Jamaica — particularly reggae and its offshoot, dancehall — has played a major role in stoking homophobia, says Henry. A number of popular songs call for queers to be beaten, burned, hanged or shot. The songs are numerous enough to have earned their own name: Outside of Jamaica, they’re often referred to as “murder music.”

“Music has played an integral part in how Jamaica responds to gays and lesbians,” he says. “Jamaica celebrates reggae music. I might be the only person who hates reggae music with a passion. When these attacks are happening, when people are celebrating them, they’re singing these songs.

“I remember in 2003 one of our friends was at this dance and this song was being played, ‘Boom Bye Bye Inna Batty Bwoy Head,’ by Buju Banton. When the song was finished playing our friend Kitty was lying on the ground with three shots to his head and that was the end of it. Nothing happened. Nobody knew who shot him.”

Henry will be working with Stop Murder Music Canada, a coalition of groups that has managed to stop several homophobic dancehall artists from performing in Canada and is trying to persuade retailers to stop selling their music.

He will also be using his position as international grand marshal at Pride to try to persuade Canadians to join the fight against Jamaican homophobia.

“To be at the front of the parade, to be representing the country I’m from, I feel honoured,” he says. “This will give me an opportunity to share with Canadians and others the harsh realities of what happens in Jamaica.”

Henry says that Canadians can help to achieve change in Jamaica by pressuring their own government.

“Jamaica relies heavily on aid from countries like Canada,” Henry says. “I would challenge all right-thinking people to think about how they want their tax dollars to be spent.”

But Henry says that first he — and hopefully his partner who will be coming to Canada in March — needs to be granted refugee status on the grounds that he will be killed if he returns to Jamaica.

“If I’m denied refugee status I’ll call my mother and tell her, ‘I’m coming home. I won’t live long,'” he says.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra