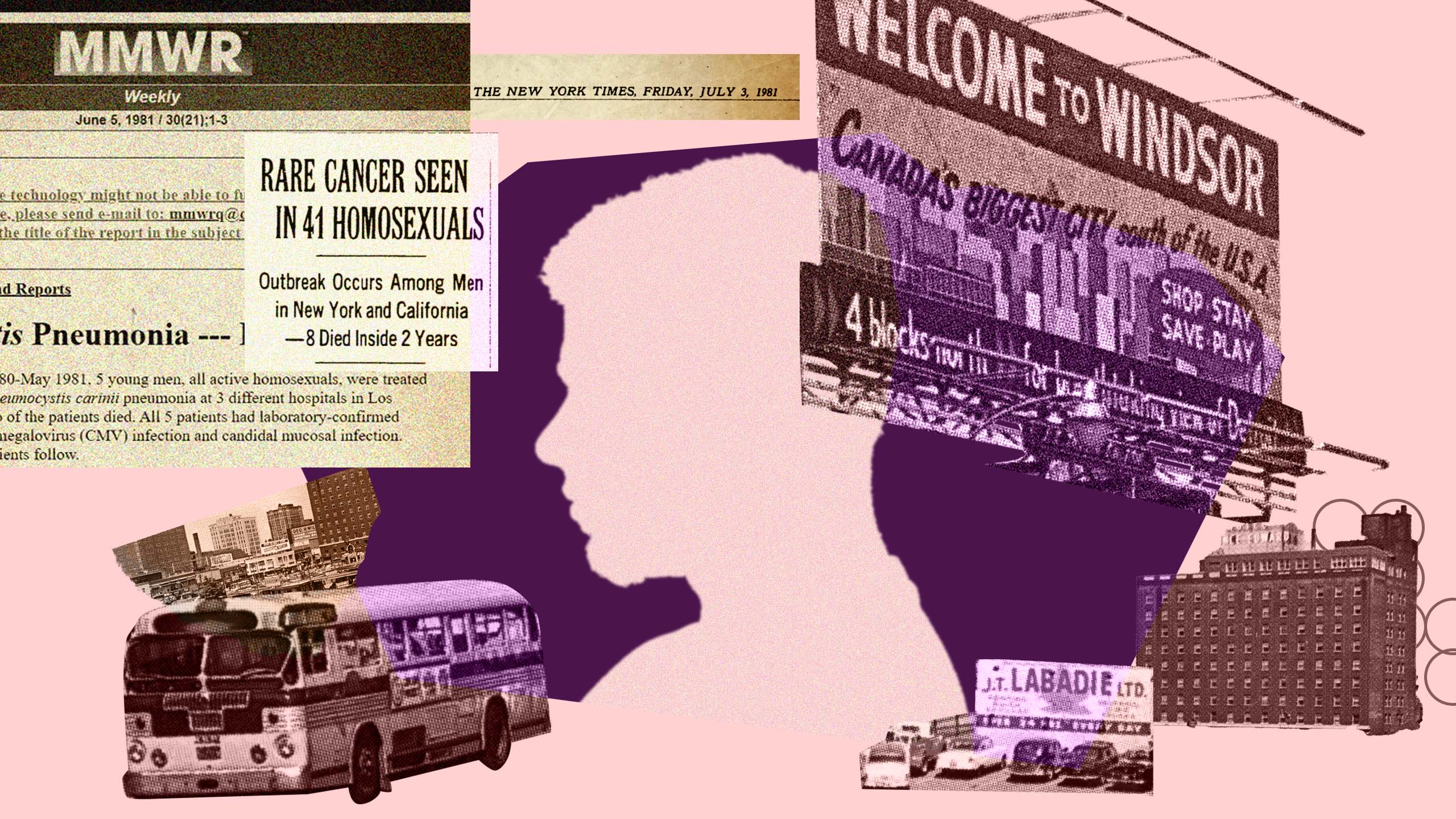

The first person who died from AIDS in Canada was reported to be a 43-year-old gay man from Windsor, Ontario. His name was never released; the news accounts and history books that marked this grim milestone never mentioned his name. This year marks the 40th anniversary of the man’s death.

I am a high school teacher and avid historian; I’ve lived in the Windsor-Essex area, across the river from Detroit, for most of my life. I am always on the lookout for interesting pieces of local history, especially LGBTQ2S+ history, with which to inspire my queer and trans students, who often know so little about the queer history of this country. And the little they do know is always centred on big cities like Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver. But hearing about this unnamed gay man really stopped me in my tracks.

I first heard about his case about two years ago from local gay activist Jim Monk, who has been active on the scene since 1972. He was chair of the Lesbian/Gay Community Service Group (LGCSG) in Windsor when the country’s first HIV/AIDS case was reported in 1982. The first reported cases anywhere in the world of what became known as AIDS had happened just a few months earlier, in June 1981 in Los Angeles.

“It was the first time AIDS became a real thing to me,” Monk told me. “It wasn’t something that was confined to California anymore … I had been reading about this thing in the States, and didn’t really think it affected us up here; I thought it involved people whose lifestyles weren’t really close to my own or to the lifestyle of gay people in this part of the country.”

As chair of the LGCSG, he started to bring up the issue locally. “It was like introducing the bubonic plague,” he recalled. Monk began to educate himself, subscribing to many medical publications and tracking all the latest research, including the political side of the issue. He became the go-to person for the early days of the AIDS epidemic. The AIDS Committee of Windsor (ACW) was formed in Monk’s apartment in December 1985.

I asked him if he knew the name of that first case. He didn’t.

I became obsessed with who this unnamed man was. What was his life like? Did his family even know? How was he treated in the hospital? My research into local history over the years has unearthed numerous AIDS cases. There are just too many of them without names. And now here was the first person reported dead from AIDS in Canada: I needed to know the man behind this frightening statistic. So began my halting, two-year-long investigation to put a name to this person.

“I became obsessed with who this unnamed man was. What was his life like? Did his family even know? How was he treated in the hospital?”

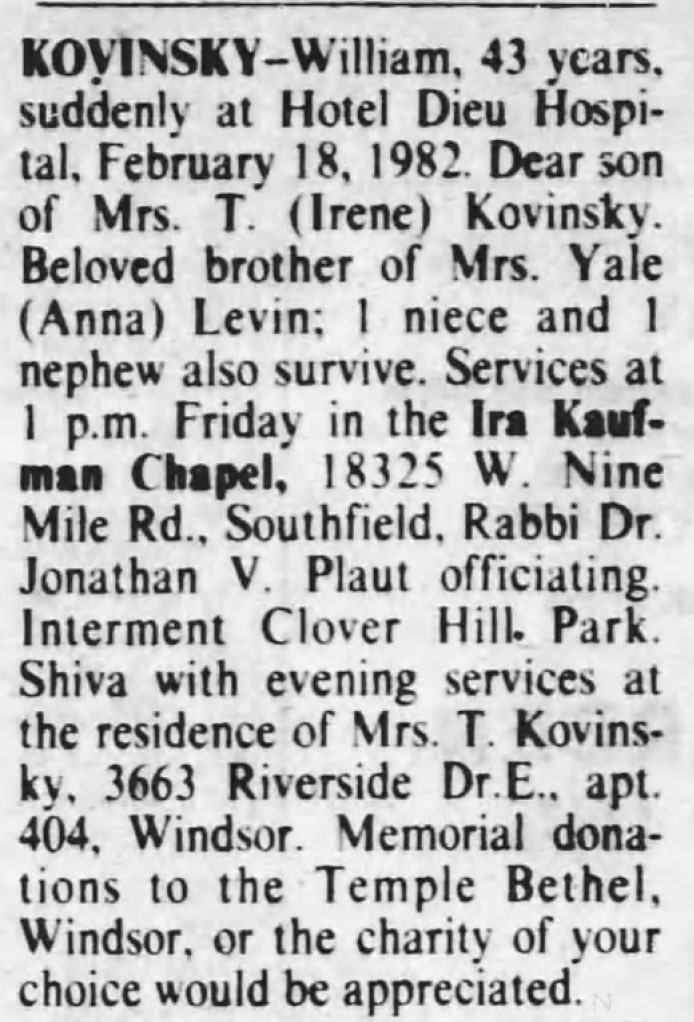

I started online and found the Windsor Star article reporting his death on March 27, 1982. I went through the obituaries in the Windsor Star around that date and found nothing that corresponded to the little information I had. I came across numerous news reports and historical accounts that repeated the same basic info, some of which didn’t even mention Windsor. These accounts left me more doubtful. Was this case even true?

It took a few days of surfing before I came across a 2002 article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ) titled, “The Disease that Transformed Medicine: AIDS Turns 20.” It was about the Windsor case, and the first account I came across that made a direct connection between the unnamed man and AIDS. The article mentioned a 1982 case report of the man’s death in the Canada Diseases Weekly Report. The CMAJ article labelled the 1982 report as “the first Canadian account of a new disease—actually a cocktail of symptoms because AIDS did not yet have that name—that was starting to cause concern in the country’s gay community. That case report: “Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a homosexual male—Ontario,” contained only 700 words, but millions more would soon follow.” A chilling sentence that gave me pause.

The article continued with recollections from the doctor who wrote the original case report. The article named him: Dr. John Doherty, “the Windsor, Ont., GP who informed the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control (LCDC) of the strange symptoms he had seen in a 43-year-old gay patient.” The unnamed man’s GP. Bingo. My first real lead.

In the article, Doherty looked back on the case and its significance.

“I still remember this case vividly because I knew the guy really well,” the article quoted Doherty. He recalled being surprised at how quickly the Laboratory Centre for Disease Control sent investigators to Windsor—they were in his office the next day. “He shouldn’t have been surprised,” the article stated, “because the centre had been waiting for such a call since June 5, 1981, when Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report carried a report on five cases of P. carinii pneumonia discovered among ‘active homosexuals in Los Angeles …’ Doherty’s patient, who had not felt well since a trip to Haiti in January 1981, entered hospital Jan. 5, 1982, and died six weeks later, on Feb. 18.”

Credit: Courtesy of Walter Cassidy

His date of death. The man had died one month before that first report I saw was published. I went back to the Windsor Star obituaries. Someone did die on that day: “Kovinsky—William, 43 years, suddenly at Hotel Dieu Hospital February 18th, 1982.” William Kovinsky. I knew instantly it must be him. It just made sense to me. Too many things had come together. But I had no proof.

I decided to try to contact any living relatives I could find. (All leads to the doctor went nowhere. I still don’t know for sure if he’s alive. I didn’t pursue him, because even if I found him, I felt he wouldn’t divulge anything because of patient-doctor privilege.)

I first looked up William’s parents. Both were deceased. I should have realized that. I had forgotten how much time had passed. My feelings of urgency really started to surface. But the obituary did name William’s married sister: Anna Levin. That’s where I focused my search. She probably would have been in her 80s by then. I simply began to contact every Levin I could find on Facebook in the Windsor/Detroit area. I asked each of them if they knew Anna Levin or her late brother, William. I told people I was doing a piece on local history and wanted to know more about William. I did not mention it was about local queer history.

After a couple of days, a relative responded to me: a niece of Anna’s. She told me she needed to talk to her aunt before she would tell me anything. I gave her my contact information. She did not give me Anna’s.

I didn’t hear from anyone for a week after that Facebook exchange. Then I got an email from Anna. When I saw who it was from, I froze. I was both excited and scared to open it. I was expecting an email telling me to leave them alone. Anna didn’t say that, but her message was very guarded. I replied, telling her I thought her brother was gay and that I wanted to find out more about his life. I did not mention how he died.

Anna and I emailed back and forth for about a week, and I kept on prodding her for information on how her brother had died. I didn’t want to say AIDS; I didn’t want to out her brother. But Anna didn’t bite. I ended up asking her directly: did she know that he had died of AIDS? I wrote to her of my suspicion that he was the first case in Canada. She soon responded, stating she had no interest in continuing our correspondence.

I was devastated.

I completely understood Anna’s reticence. You just have to look at the history of how Gaëtan Dugas was treated. Dugas, a Montreal flight attendant, died of AIDS in 1984. He was branded “Patient 0” by Randy Shilts in his 1987 book, And the Band Played On. The 2019 documentary Killing Patient Zero examined how the myth of a so-called patient zero, a first AIDS carrier, remained so potent because of people’s need for a villain. Dugas’ humanity was shunted aside in misguided attempts to blame someone. Little matter that Shilts had misread the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study that tracked sexual activity in gay and bisexual men in New York and California. Dugas was coded as “patient O”— meaning “out of state”—not the number zero. Even though the idea that Dugas was somehow responsible for beginning the AIDS epidemic has been debunked many times, it took a 2016 study that sequenced Dugas’s HIV genome to finally disprove it without a doubt. The Killing Patient Zero doc noted that, to this day, the Dugas family will not talk about him publicly because of all the hate and fear this misunderstanding created for them.

I decided to email Anna one more time to try to convince her that I wanted to tell her brother’s story; to replace a statistic with a real, flesh-and-blood person. I assured her I wouldn’t publish anything without her approval. I also cautioned that if I was able to figure it out, someone else would, too. Wouldn’t it be better to ensure the story about her brother was something she could be proud of?

She agreed to chat with me on the phone. This was my chance. I explained how I wanted to tell his story and, as a teacher, how I wanted future generations to know the truth about his life. Anna told me that some members of her family were against her talking to me, but that, in the end, her daughter had convinced her otherwise. Never quite losing that guarded nature of her first communication with me—and me always worried about pushing her too far—Anna finally agreed to give me her brother’s story. One of the first things I learned was that everyone called him Billy.

This is Billy’s story.

Credit: Courtesy of Anna Levin

Born in 1939, Billy Kovinsky grew up in Windsor and went to J.L. Forster High School on the west side of the city. Anna was only 13 months younger than Billy. They were very close, and at times people thought they were twins. The siblings were part of the school’s drama club, and performed in several shows. In 1957, the school yearbook noted that “one of the main attractions of Variety Night was a comedy entitled ‘How to Propose.’ As a marriage lecturer, Bill Kovinsky gave invaluable suggestions to prospective poppers of that well-known question.” They both worked together on the organizing committees for school dances. Billy also joined the school cadets group. Anna told me that he was very cute and popular with the girls at school.

One of Anna’s memories was that teenage Billy had strong friendships with two male classmates. The three of them would dress in women’s clothing and makeup every Halloween. They remained friends their whole lives. One died in 1989. His obituary stated that he died of cancer while living in Toronto, and was a “benefactor to his adopted Haitian family.” The other died of cancer in 1999. Neither ever married.

Credit: Courtesy of Anna Levin

Anna told me that Billy’s high school years at Forster were very positive. He was never bullied. In his 1958 graduation yearbook, Billy’s picture included the caption “Daddy’s boy,” and it noted that he would run his “Pop’s Business” in the future. Which he did.

Billy grew up with privilege. His family was part owners of J. Kovinsky & Sons, a successful scrap metal recycling company located on the riverfront. (The family sold the company in the mid 1970s; it’s now K-Scrap Resources Ltd.) Anna said that even though they came from an affluent Jewish family, they were brought up modestly and did not flaunt their prosperity.

Billy went to the University of Windsor to study business, but dropped out after two years to work full-time at his father’s company. Anna said that Billy learned at an early age to keep his private life separate from his family and professional life. He was even engaged once in his late 20s, to a woman, but the engagement was broken off after two or three months.

After high school, Anna went to Michigan State University, fell in love and moved to Michigan permanently. Billy, meanwhile, spent 20 years at the scrapyard, eventually selling his 50 percent share of the company. He decided to “retire” in 1974 and travel extensively. He went to many places to escape his “straight” persona and be free and gay in other places, Anna said.

From my own research, I know it was common for queer people in Windsor at that time to have a double life. Many Windsorites would cross over to Detroit to go to the gay bars at night and live a straight life during the day in Windsor. Billy was likely no different. Anna knew he partied in Detroit often. Many times, he would end up sleeping over at her house in Michigan instead of going back to Windsor. He never told his parents or his sister that he was gay, but Anna always suspected. She said there were many signs, such as a bathroom covered in erotic wallpaper in his Wilcox Avenue house in South Windsor.

Retirement only lasted two years, and then Billy became a stockbroker for Mead and Company Limited, a job he kept until the day he died. In 1975, Billy moved into the penthouse of the newly built Ouellette Tower Apartments in downtown Windsor, which was walking distance from work. He even paid extra to have the place altered from the original architectural designs, and his apartment was featured in the Windsor Star. The article highlighted the beautiful décor and the fabulous view of the river.

Credit: Courtesy of the Windsor Star

After the 1967 Six-Day War between Israel and surrounding Arab countries, the local Jewish community centre sent Billy and some other Windsorites on a fact-finding trip to Israel, where he met Golda Meir, and Anna recalled he later reported his findings in a speech back in Windsor. Billy admired Meir and kept a photograph on a wall in his home showing him shaking hands with her.

Anna believed that Windsor was never truly safe for Billy. She remembered one horrible incident that Billy shared with her. In the late ’70s, Billy had invited three men over to his apartment. They beat him up, hung him over his penthouse apartment balcony railing and robbed him. The three men were caught and convicted, but the case never hit the papers.

Billy travelled often, collecting objects to decorate his home, which was full of books, records, pewter, brass and paintings. He even invested in Broadway shows and a Hollywood movie. Anna said the best way to describe him was that “everything about Billy was enchanting.” She lived the conventional life while he lived a larger-than-life adventure. Billy toured the world. The newspaper would publish his adventures in the 1960s, detailing his trips to Madrid, Mexico City and to Montreal during Expo 67.

Credit: Courtesy of Anna Levin

In 1968, the Windsor Star published an article on local eligible bachelors for Valentine’s Day. Billy and one of his friends were interviewed for the article. Billy said he wasn’t planning on getting married, but that it was a pleasant thought. He said his ideal woman was sporty, extroverted and had an inner beauty, but he admitted that he was too busy—working, attending the theatre and travelling—to think about girls.

Billy lived his whole life in Windsor, but in the late 1970s he purchased a condo in Fort Lauderdale with his good friends Jack and Phyllis (both now deceased). From there, it was convenient for him to frequently travel to Haiti or Mexico. The last pictures of Billy that Anna has were from a visit she made to Florida for Thanksgiving.

When Doherty filed his case report after Billy’s death in 1982, he noted that Billy would visit “homosexual communities” in Toronto, Detroit, New York, San Francisco and the Caribbean. He was also known to have taken recreational drugs, like poppers. He frequented the gay scene in Detroit a great deal, and would stay over for the weekend with his gay friends in Birmingham, a suburb just north of Detroit. He usually visited Anna on the way home. She recalled one time he showed up “looking like one of The Village People,” and it was obvious to her he was on something. He didn’t seem himself. Anna told him to never to show up like that again, and he never did. But his health was changing. As far back as August 1979, he was starting to get worried. His medical report stated that he showed abnormal levels of immune globulins, something that in later years scientists would connect to people with untreated HIV.

Credit: Courtesy of Anna Levin

In March 1981, according to Doherty’s case report, Billy went to see him again and was diagnosed with enlarged lymph nodes. In April of that same year, his immune globulins were normal again. Then in May, he saw a Toronto physician, complaining of gastroenteritis and weight loss. He got a blood test, and his white blood count was “extremely low.” In June 1981, his sister saw him at the Florida condo, and he did not look good. “He was very thin and gaunt and suffered from sweats,” Anna recalled. He went back to Canada that same month to the University Hospital in London. Laboratory tests showed “leukopenia, atypical lymphocytosis and an elevated sedimentation rate.” He was admitted to the hospital for eight days and discharged after there was no firm diagnosis.

“No treatment was given,” stated the case report.

Billy was actively trying to find out what was wrong with him. No doctor could help. I can only speculate this resulted in a huge emotional and physical burden on him. The 1982 report stated that he became very depressed and had attempted suicide in August 1981 by taking 100 tablets. He spent two days in hospital and was sent to Toronto for four weeks of psychiatric treatment. His sister remembered that time and how difficult it was. Billy’s best friend, Jack, always had a quip for any occasion, and she recalled that he said, “Billy, if you had died, we would have buried you in a pink dress.”

By December, Billy was once again not feeling well and had a gastroscopy exam. It was discovered that he had monilial infection, or thrush, covering the entire lining of the esophagus, from mouth to stomach. In January 1982, he was admitted again to hospital in Windsor. Many more tests were performed on him, according to the case report, including an “open chest upper lobe biopsy.” Anna would visit Billy three times a week; his friends Phyllis and Jack would also visit. He had his own room, and Anna recalled that he was treated very well by the staff at the hospital.

At home, Anna found an article in The New York Times citing a new disease called GRID (gay-related immune disease), what doctors called HIV/AIDS in those early days of the disease. She was convinced that this was what Billy had because he exhibited most of the symptoms. She decided to tell his doctor, but wasn’t sure how to do it. She and her brother had never talked about his sexuality and in those days, broaching the subject wasn’t something you could be very open about. She discreetly pressed the article into the doctor’s hand and asked him to read it. She and the doctor never talked about it afterward.

Billy was getting worse; he stopped eating. They forced a feeding tube down his throat. Three weeks later, he died.

Anna gave me a copy of the tribute given by Rabbi Dr. Jonathan V. Plaut two days after Billy died. It was filled with wonderful memories of his professional life. One section jumped out: Plaut described Billy as “honest and sincere. He was loving and had a warm personality. He was over-enthusiastic. He was not afraid to tell you how he felt. If he did not like you, he never said a bad word about you, he would just ignore the individual.” That is how Billy lived his whole life. It was a tribute full of kindness, sadness and loss, but it did not include anything about his friendships or any hint of an alternative life.

Billy’s doctor told Anna that, because of the strangeness of the case, he wanted to do an autopsy. She agreed. Billy was given a diagnosis of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP). Doherty never discussed his suspicions around AIDS—or GRID—with Anna, but she knew that there was something unusual about Billy’s case. “The physicians in the hospital participated in a medical round-table discussion,” she recalled, “and the results were shared with other medical professionals.” Anna told everyone that PCP was the cause of death. But she had her doubts. “I just put it together myself by connecting my suspicion of his private gay lifestyle and the article from The New York Times,” she said.

According to Doherty’s report, Billy told him that his illness made him impotent, and that he hadn’t engaged in any sexual activity since April 1981. He had been trying to get help since 1979. The first published U.S. report about AIDS came out on May 18, 1981, written by Lawrence Mass, a gay doctor in New York. In June that same year, the CDC reported on the five gay men in Los Angeles who had come down with PCP, and in July, The New York Times reported on 41 gay men in New York and San Francisco who had developed Kaposi’s sarcoma. In August of that year, the CDC had coined a new name: acquired immune deficiency syndrome—AIDS. By December, close to 400 people had been diagnosed with the disease in the United States. The Canadian medical community never publicly made the connection to Billy’s case, even though Anna did. Canadian health professionals knew there was a disease killing gay men, but it was still too early to connect the symptoms. Billy had no history of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

Billy Kovinsky was the first reported case of someone dying of the disease in Canada (we now know of an earlier case who died in 1979, diagnosed retrospectively). Since Billy’s case happened so early in the epidemic, he did not have to endure the difficulties many people had to go through later. Local activist Barry Adam, a member of the LGCSG, recalled those early days around 1984 in Windsor in the 2010 book, Out and Aging: Our Stories. When he would go to the hospital to visit friends with HIV/AIDS, Adam would have to be wrapped up in personal protective gear. The hospital staff were totally covered up and, when feeding AIDS patients, he recalled, they would only “push the food under the door, and wouldn’t come in.” The healthcare system failed AIDS patients in the beginning. In 1984, the city saw four more people die from AIDS, and by 1995 there were hundreds who died in Windsor alone; Canada saw a peak of 1,764 deaths that year. From 1980 to 2013, Canada reported 14,381 deaths; 12,946 of those deaths were men.

Billy is buried in the family plot at Clover Hill Park Cemetery in Royal Oak, Michigan, alongside his parents, aunts, uncles and cousin. Anna wants her brother to be remembered as a smart, well-read, accomplished, witty, culturally informed man who was also very down to earth. He enjoyed his wealth but did not flaunt it. Billy was impeccable in his appearance and never gaudy. Billy was loved by his family his whole life.

“Uncle Billy was larger than life to my children,” Anna said. “They looked forward to his visits; he fascinated them, played games with them and made them laugh. He was charismatic and charmed them all the time.

“Billy had a very full life that was divided into two parts because of the mores of the times. I often experienced life vicariously through Billy because he would bring me beautiful gifts from his travels and tell me about the wonders of the world. His life was so multifaceted, and mine was the norm. Billy was the larger-than-life bachelor. He had what I did not have, and I had what he did not have.”

Anna gave a large portion of Billy’s record collection to two of his best friends from high school who shared his love of music. His books (embossed with his name in memoriam on a bookplate) were donated to J.L. Forster and the University of Windsor. I have no idea what happened to the books after Forster was closed in 2014. Anna has incorporated Billy’s artwork into her home, and she treasures the photograph of Billy and Golda Meir. There is a strong presence of Billy in her house.

Credit: Courtesy of Anna Levin

After learning his story, I cannot help but have mixed emotions about the journey of discovery I went through getting to know Billy through the eyes of his sister. I am glad to have his story told and to know that he wasn’t alone when he died, and that he had his closest friends and family around him till the end. I also feel sad that he never got to know what was ailing him. The fear, frustration, even hatred he must have gone through struggling to trust the medical establishment as it tried to find out what was wrong with him. Him never knowing. Or did he know it? People were already dying in the United States, so it is possible he knew. His sister figured it out. Maybe he did, too, and he didn’t tell anyone just the same way he didn’t tell anyone in his family he was gay.

I am also glad for the life he did get to lead, short as it was. He had a privileged life and had many advantages others could only dream about: a beautiful apartment, no money issues, world travel and a family who loved him. But none of the conversations I have had about him included a “special friend,” either.

He was lucky, too. Billy never had to endure the hardships, the prejudice that thousands of gay men diagnosed with HIV/AIDS after him would have to undergo. He avoided the paranoia, fear, loneliness, rejection and hate so many gay men experienced in those years when the epidemic hit the community so hard; when there was so much panic and confusion and desire to blame people.

Anna just wishes she and Billy knew each other in more tolerant times, so he could have felt more open with her about his personal life. Anna still remembers the quote from Hamlet that was said at his eulogy, “Good night, sweet prince/ And flights of angels sing thee to thy rest.” Forty years later, it still makes her emotional. Billy is missed immensely.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra